After Fireflies’s acclaimed release in 2018, we are thrilled to present our July Book Club selection: Luis Sagasti’s A Musical Offering, the Argentine author’s second translation into English by Charco Press. Out this month in the UK alone, it is an early gift to our subscribers overseas. And what a gift it is: adding plenty of heart to the author’s signature heady humor, this exquisitely lyrical, genre-bending work explores music’s ties to everything from sand paintings to stars—and above all, perhaps, its ability to ward off death and loneliness.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

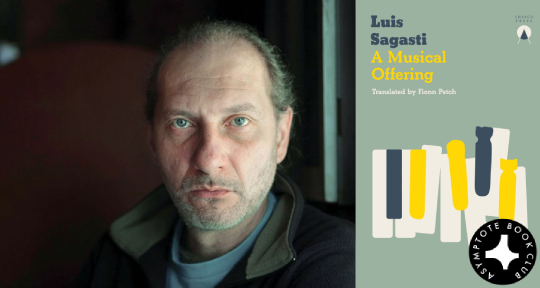

A Musical Offering by Luis Sagasti, translated from the Spanish by Fionn Petch, Charco Press, 2020

In his classic Gödel, Escher, Bach, Douglas Hofstadter waxes lyrical about the German composer’s BWV 1079. The Musical Offering is, he claims, J.S. Bach’s “supreme accomplishment in counterpoint”: “one large intellectual fugue” rife with forms and ideas, hidden references, and cheeky innuendos. The same could be said of Luis Sagasti’s near-eponymous book (the author humbly drops the “the” for an “a”), out now from Charco Press in Fionn Petch’s seamless rendition.

Anchored in music itself, this magpie suite of literary bites spans centuries, geographies, and disciplines. It opens with an allegedly nonfictional one-pager on the birth of the Goldberg Variations, another Bachian staple: in the retelling, Count Keyserling requests a musical sleep aid, to be executed nightly by the young virtuoso after whom it’ll be later named (a fetching origin story, no doubt, though I must side with those who think it apocryphal; as a seasoned insomniac, I can’t fathom sleeping through the shift from mellow aria to zesty first variatio, let alone the jump to outright fervid fifth).

Whatever its epistemic status—much of the book waltzes gracefully from fact to fiction—the narrative soon leads to something like a micro-essay packing a Borgesian punch: is Goldberg an inverted Scheherezade, Sagasti wonders, his endless performance meant to usher in sleep’s “little death” rather than stall it? These musings, in turn, link to a personal anecdote—the author humming his favorite lullaby—echoed in what can only be described as aphorism: “When a child first learns to hum a melody, the child stops being music and (…) becomes [its] receptacle” (or, ditching poetry for pop, “No child could fall asleep to [the Beatles’s] ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’”). This is just a sample; a thousand and one ties can be drawn among snippets on music and sleep, silence, space, or war, not just within the book’s broadly themed sections but across them—a veritable fugue of insights and literary forms.

Sagasti also boasts Bach’s subtlety and humor. We’ll miss the link between an entry on a Leningrad grandmother’s bedtime stories and another on the film Glenn Gould’s Toronto, for instance, if we haven’t first watched the latter and heard Glenn mention the old Soviet town with fondness; the wordplay present in “Himmelheim”—the name of a fictional village whose dwellers build a sky-scraping organ—will go right over our heads unless we do a little digging and find, through Google’s grace and power, that himmel means “heaven” and heim, “home.” Other jabs are more readily accessible: in 1977, the author reminds us, the Voyager probe was launched into space with a disc of earthly sounds meant for possible intergalactic neighbors; unfortunately, the Beatles’ record label “refused to let the song ‘Here Comes the Sun’ be added to the journey.”

Hofstadter might have similarly raved about Sagasti’s musical offering, then, but he would have fallen short. While, like Bach’s, it’s a “beautiful creation of the intellect,” that doesn’t quite do justice to its name; what takes it from dazzling gimmick to gift is its heart. There are many moments in which the author plucks our emotional strings, often right after he’s landed a punchline with cool-kid agility (like Leonard Cohen, that other Canadian master featured in his epigraph, he knows that minor fourths and major fifths hit best in close succession). Fundamentally, though, his fugue draws its soul from two subtle but prevalent themes.

The first, I’d venture, is loneliness—or, on a brighter note, music’s power to ward it off; “the greatest sufferings,” after all, “are always silent.” Thus, Sagasti tells us, composer Karlheinz Stockhausen “hears only birds during that week of fearful solitude” after his wife deserts him; the so-called “silence of Bayreuth” at the famed Wagnerian Festival gives Mark Twain the impression that he’s sitting by himself amid the dead; the largely silent sixth movement of Messiaen’s From the Canyons to the Stars is an unanswered “interstellar call”; pianist/Argentine political prisoner Miguel Ángel Estrella’s isolation turns to torture when his guards bash his instrument and render it mute; soldiers stranded in lone islands hear a “silence broken only by the waves,” and somewhere in the North Pacific, “the loneliest whale in the world” sings a song his peers can’t hear.

If silence and solitude go hand in hand, so do music and communion—be it via hymns that spread through concentration camps like viruses, or choruses that travel from pavilion to pavilion in Argentine jails, or British icon Pete Townshend’s own chorus line You are Forgiven, addressed to everyone who’s ever wronged him. So powerful is music’s potential for unity, in fact, that it can make five staunchly opposed mayoral candidates smile in unison, or put baby Hitler and Chaplin to sleep all at once. Meanwhile, when Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony debuts in the streets of besieged Leningrad during World War II, German soldiers posted in the city outskirts are moved to question their loyalties. A parallel: Scheherezade’s spoken songs end up making a lover of her would-be executioner.

In doing so, of course, they also push back death, the other solitude that haunts this book. One night, says Sagasti, Scheherezade stumbles upon Death incarnate in the desert as he is picking the finest sand for his hourglass. He explains that she should have seen “the last star allotted to [her]” three years prior, but was spared because “[she] began to tell stories.” Playing songs, it appears, can have much the same effect, sometimes quite literally. Like many of his wartime colleagues, for example, Shostakovich is pulled out of the front line because “musicians are essential when death is imminent,” and a Nazi camp prisoner finds in a fellow inmate’s pending aria “a reason to live until tomorrow.”

But how do we keep a song—a life—from ending? Sagasti hints at a number of ways. We might leave it hanging, like those Navajo sand paintings that “form a door to the other world” and must be left unfinished in order to keep a “double lock on the gates.” We might mimic Samuel Barber’s Beethoven’s Tenth Symphony, in which everything’s about to end but seemingly doesn’t: “the very sound of imminence.” We might stretch it out as much as possible, like John Cage’s 1985 ASLSP, now playing in Halberstadt at a rate of roughly one movement per seven decades, courtesy of three small bags of sand placed on an organ’s keys. We might be swept back to childhood, to the “pure present” of a “mother’s milk,” like harpsichordist Wanda Landowska’s sleigh driver upon hearing her play.

It seems, however, that the best way to “remove” a song (ourselves) from the cruel “flow of time” is to play it over and over. That is Scheherezade’s hidden ace: one night, she tells her own story—that of someone who postpones her death with a nightly tale—and this mise en abyme “leaves death outside” because it re-launches the series. She’s not alone: Sagasti’s book reveals a powerful, widespread drive to (pun intended) “stave off death” through circularity. There’s the Australian didgeridoo’s perfectly round and therefore presumably endless sound; the Beatles’ clever, loop-like tricks to prolong “A Day in the Life,” “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and other suggestively named hits; The Who’s conviction that wrecking their instruments at the end of a show is “not an end but the restless pulsing of a world that is being born.” And so on ad aeternum.

Sagasti doesn’t merely recount such attempts to bond with others and save ourselves through word or song; the very structure of his book is a case in point. Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Bach’s giddy first biographer, praised his ability to combine different parts in his fugues: “If the language of music is (…) a simple sequence of notes,” he said, “it can justly be accused of poverty (…). True harmony is the interweaving of several melodies.” By avoiding a classic narrative sequence and allowing distinct fragments to converse, Sagasti achieves this same formal harmony—which is, of course, a mode of communion.

It is also a way of arresting death. Like the voices in Messiaen’s Awakening of the Birds, these overlaid fragments connect to each other in no particular order, achieving a welcome confusion that “does away with time.” Sagasti’s boldest move on this front, however, comes at the end of the book. Its “Da Capo” section harks back to the Goldberg Variations’ closing “Aria da Capo,” a note-for-note repetition of the opening theme, which “introduces the idea of circularity” because “everything starts over” (“da capo” means “from the top”). But the author takes it one step further: Bach’s exact directive is “da Capo al Fine,” instructing performers to execute the aria again just once before concluding the piece; Sagasti skips the qualifier, prompting us to play his musical offering in an infinite loop.

And yet, it seems, the content of his “Da Capo” renders its form futile. It closes with an account of a young Glenn Gould “fixated on just one [piano] key, pressing it down until the sound fade[s], over and over again (…), insisting on what can only cease.” This otherwise charming anecdote cautions that every song must end, all efforts to the contrary be damned.

The undertone in minor key: we’ll die one day, and die alone. The major coda: we’ll have music like Sagasti’s while we live.

Josefina Massot was born and lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied Philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for the Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is currently a freelance writer, editor, and translator, as well as an assistant managing editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: