In this week’s Translation Tuesday, a young woman’s sense of self-worth is prey to the forces of contemporary domestic servitude in Allan Derain’s “Anatomy of a Servant”. What begins as an endearing epistolary abruptly shifts to the perspective of our narrator, Asunta, as she seeks to build a better life for herself. The servant’s body becomes the target of dehumanization on the basis of class, gender, and nationality, until Asunta’s consciousness comes to internalize these repeated acts of violence as “necessary” and even “deserved”. Across these three short sections, Derain explores the classed anxieties of a dutiful daughter who longs for a brighter, freer future, though who also longs for home.

I. Empty-Headed

May 4, 2004

My Dear Asunta,

Before anything else, how is my good daughter? I hope you’re doing well. Are you eating on time? If you’re wondering, don’t worry about us. Marissa will be in high school the following school year. Your sister is looking for cash, so she now mans Tonga’s store. The money you have sent is enough, but we know that you are saving for something important. More people are asking me to sew, now that school is about to start.

You wrote in your last letter that the old man you attended to has already passed away. Does that mean that you can now come back home? Our fiesta will begin next week. I am part of the dancing group who will perform the Alembong in the parade. Don’t worry, and I’ll send you a picture so that it’ll be as if you were here in the fiesta . . .

This was what she always did: gazing out the window early in the morning. It was only yesterday she received the letter but by now, she had already read it countless of times as she faced the window. She glanced at her watch. She had thirty more minutes left to have the world to herself.

She freely let the brackish breeze from East Coast Park enter the room. On her first day here in the roof-tiled bungalow, one among the small shops and teahouses that could be seen in the fishnet-like alleys, it was that same harbor that had caught her attention. Boats of various colors docked there; some were anchored, some still searching for a quay to dock to and some perhaps just about to depart to another country. Which of these were bound for the Philippines? She had been slowly reconstructing the whole Manila Bay in her mind when the bell rang from her boss’s room.

She quickly entered the room and there, the old man’s glare received her. The room stank of incense and medicine. The old man muttered something so Asunta took two steps forward. But in the end, she did not understand anything. The old man spoke again, but for Asunta, it only consisted of groans and meaningless words. The young woman put her ear closer to his mouth. But, as she was doing this, she was hit by a walking stick. One for being deaf and another for being stupid.

“Botawkak! Wanapo di tswekang yaban botawkak!” Only her boss, who was a doctor, spoke in English. The old man, like the other old people of that country stayed faithful to his language.

That’s why Asunta started noting down the words. She learned how to use a dictionary. Kakin-kakin means “fast.” Yaban is “slow.” Wanapos a “Filipino helper.” She now knew that botawkak means “stupid,” in Tagalog “tanga,” “hindi ginagamit ang ulo,” or “bugak” in their home province.

The old man she took care of was an invalid. Why he had not been treated by his son, who was an orthopedic surgeon, Asunta had no clue. But she now knew that it was not only her whom the old man called “botawkak.” Both the doctor and herself were insulted for being stupid.

But this morning, there was no more old man to nurse. She now had only one thing to attend to. There was no bell to disturb her leisure. Like now. A boat from the dock she had been staring at was drifting farther. Perhaps this was now the boat set for the Philippines.

Asunta’s thirty minutes of daydreaming had finished. She was ready to face the eighteen-hour workday ahead of her.

II. The Work of Her Hands

As soon as she went down to the laboratory, the young woman immediately noticed something: an empty cage. Her boss preferred to operate on cats. If it went missing, the laboratory was amiss. She remembered that the other day, five cats had been fighting for a piece of bread.

But, today, this was not among her many concerns. Not the cat.

With her hands covered by scratches, she pulled the cage toward the faucet to wash it. After she rinsed the cage, she began to spray disinfectant over the tiles. The environment should smell like alcohol, she decided. For Asunta, the lab was the opposite of what she considered ordinary. Once she entered it, she was no longer Asunta the help. Instead, she was now Asunta C. Ibayan: a graduate of nursing from Fatima, a former intern of Cardinal Hospital who had taken the board exam and passed, and was now a laboratory assistant for her boss, an orthopedic surgeon.

“If you could only see me now, Mother,” she said to the only photograph stuck to the frame of her mirror.

That self-image of hers was reaffirmed now that she was surrounded by test tubes and flasks lined up on a shelf, electric lights beaming in all directions, an operating table that could be adjusted to different positions and the syringes, scissors, and scalpels with wide-ranging shapes, sizes, and sharpness.

One by one, she laid them out on the tray like a dance. She had also memorized their names one by one: the scalpel which was the primary instrument for incising, the retractors for parting the edges of incisions, and the hemostats for clamping the flow of blood.

Within an hour, she had already arranged the instruments. She had sterilized what needed to be sterilized. Now, she was scrubbing the floor. First, she cleaned her favorite spot where the mirror was. While her hands were busy, her eyes focused on her mother’s photo. She was wearing a kimona’t saya which she knew had been borrowed for a dance. Many said that they looked alike. This photo had been sent at the time of the fiesta, so the color had faded. She would need to cover it in plastic, she thought.

She pitied her mother. She sewed clothes for others, but she could not make a gown even for herself. It was only the other day when she had sent a letter. She was asked to come home. Because of exasperation, many Filipinos were now returning from Singapore. Even her neighbor who went abroad with her had already come back to the Philippines. Though she had not been allowed to go out of the house, she knew what was happening. The news about a fellow domestic helper who had murdered another Filipina domestic helper had already spread. But she would not leave. Not now. This was what Asunta had decided. What she had planned for her life would not be ruined because of another Filipina’s mistake. Besides, not all bosses were as stern as the old man who had recently passed away. Her remaining boss was a clown. He often joked—if it had really been a joke—that Filipino maids, these wanapo, whenever they received their salary, would always spend it on pants so they saved nothing at all. She should not be like them. She should try to save whatever it takes. She should not waste each passing hour and day and should always strive for what was best in life.

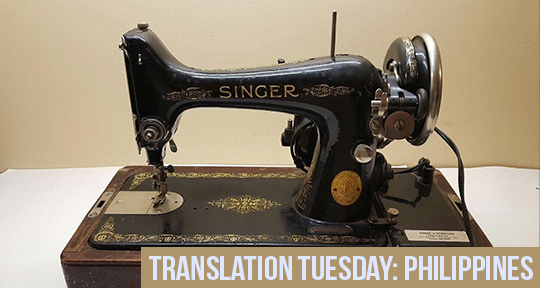

What, for her, was the best thing in life? Her boss had asked her last night. A polished sewing machine quickly came into mind. New and elegant. It represented a seamstress’ pinnacle of luxury. It was as if Asunta had again heard the squeak and whirr her mother made while pedaling the manual machine. This had not been theirs. Her mother had to leave home just to use the machine.

Asunta turned again toward the cage. Still nothing was inside. But she didn’t really need a cat today.

III. And Other Bound Parts

When her boss went down, his eyes scanned around. Everything was in place. His assistant was certainly dependable. They could now begin the operation.

It will be quick, assured the doctor while fitting the rubber gloves. Aside from the fact that he knew what he was doing, how many times had he operated on cats who had woken up?

Asunta simply stared at the ceiling. She was blinded by the bright light, so the doctor adjusted its focus to her legs. The doctor had always wanted to closely study the evaluation and suturing of the kneecap from a real live human being.

As to why her body was stretched there, Asunta didn’t entirely comprehend. But she didn’t think this was an act of sacrifice. Rather, she wanted to take it as a form of punishment for her sins which were, one by one, coming back to haunt her: the classmate she stole a bracelet from in fourth grade, Marissa’s piggy bank she pilfered from every day, the board exam she cheated on, and the invalid she slowly poisoned by his son’s orders.

Now, their marbled eyes’ glare altogether hinted their insinuations from the pile of trash, under the car in the garage, from the darkest corners of alleys, under her wooden bed . . .

After the syringe was administered, numbness slowly crept over her whole body. Asunta’s body slept but she remained conscious. She heard the whir her mother made with her new sewing machine.

Translated from the Filipino by Bernard Capinpin

Allan N. Derain is the author of the short story collections, Iskrapbuk and The Next Great Tagalog Novel, and the novel, Ang Banal na Aklat ng Mga Kumag, which won the Grand Prize for the Novel in Filipino in the Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature.

Bernard Capinpin is a poet and translator. He is currently working on a translation of Ramon Guillermo’s Ang Makina ni Mang Turing. He resides in Quezon City.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: