One of the greatest pleasures of a text can result from its echoes throughout other mediums, when we startle upon the themes and traits of our most cherished authors beyond the page. In this essay, Austyn Wohlers traces the dialogue that forms between lauded Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector and visual artist Lygia Clark, most notable for their mutual application of animality and wildness.

Clarice Lispector’s fascination with animal life is one of her defining qualities as a writer: readers may be familiar with G.H.’s fateful encounter with a cockroach in The Passion According to G.H., or Lucrécia’s bodily identification with horses in The Besieged City. Her ideas about how animals affect the humans who encounter them were complex, as one can see in this excerpt from her posthumously-published novel A Breath of Life, referencing Lispector’s real-life dog Ulysses:

Contact with animal life is indispensable to my psychic health. My dog reinvigorates me completely . . . All he does is ‘be.’ ‘Being’ is his activity . . . When he falls asleep in my lap I watch over him and his very rhythmical breathing. And—he motionless in my lap—we form a single organic being, a living mute statue.

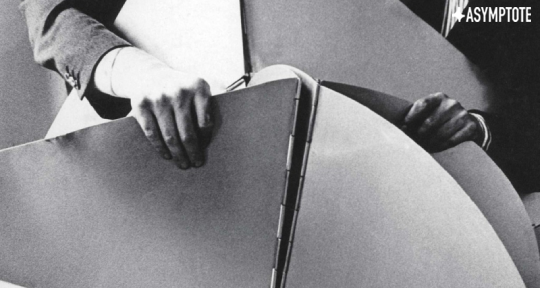

This description of animal-human contact as a “living mute statue” reminds me of Lispector’s contemporary (and fellow Brazilian) Lygia Clark’s Bicho sculptures. Mostly created in the early 1960s, the Bichos were a series of unique sculptures largely designed to be handled, manipulated, and warmed by the viewer as one would hold a small animal. In The Abandonment of Art, Cornelia Butler writes that she “imagined the encounter with [the Bichos] as something like an exchange between two organisms”—forming, in other words, the same “living mute statue” that Lispector describes. Both Lispector and Clark use human contact with animals as a way to get closer to a paradoxical self-alienation that leads to self-actualization: Clark’s empty-full (vazio-pleno), described by Suely Rolnik as the moment “when the silent incubation of a new reality of feeling is underway,” and Lispector’s wild heart—the thing itself—the it.

The word bicho does not have a direct cognate in English, and is usually translated as “beast,” “critter,” “animal,” or “pet.” The word in Portuguese has a diminutive quality, so the cutesiness imparted by words like “critter” and “pet” convey the tone well, and communicate the lighthearted spirit with which Clark expects viewers to play with the Bichos while palliating—or perhaps humanizing—their more serious, transformative, “living mute statue” nature. Interestingly, the word bicho appears often in Lispector’s writing, and though Lygia Clark’s usage is often translated as “critter,” Lispector’s is translated as the more serious word “animal.” Elizabeth Friis provides a few examples from Lispector’s novel Água viva in her essay “In my Core I have the Strange Impression that I don’t Belong to the Human Species: Clarice Lispector’s Água viva as Life Writing?”:

Ás vezes eletrizo-me over bicho.

Sometimes I get electrified when I see animals.Os bichos me fantasticam.

Animals fantastricate me.Não ter nascido bicho é uma minha secreta nostalgia.

Not having been born an animal is a secret nostalgia of mine.

Friis cites Stefan Tobler’s translation, which renders the word “bicho” as “animal,” as well as the closer Portuguese cognate, “o animal/os animais.”

Preciso setir de novo o it dos animais . . .

I need to feel again the it of animals . . .

What is lost in translation to Anglophone readers is the playfulness of the word bicho[s] in contrast with animais, although a certain lightheartedness in these first three quotes is still palpable in Tobler’s translation—the silly nonword “fantastricate,” the cartoonish visual of electrification, the coy furtiveness of her “secret nostalgia.” Lispector’s move from the word bicho[s] to animais when speaking directly about the it is a linguistically subtle indicator of her increasing gravity as she nears the it. When we speak of critters, we can pretend our lives are breezy and incidental; when we approach the it, a more serious word is needed.

Most of Clark’s Bicho sculptures were made to be handled, and to feel individual. All of them have unique titles, and, as Monica Amor details in her book Theories of the Nonobject (2016), are made with a variety of metals, including “aluminum, stainless steel, and with gold patinas,” sometimes painted “metallic silver and green,” and all “executed in three sizes,” much as cats and dogs appear in different breeds, sizes, and coat patterns. The human handling of the Bicho is central to their concept, as is the fact that the Bichos themselves seem to interact with the participant; they resist certain bends of their metal and cede to others, instead of submitting wholly to the handler. As quoted in Amor’s book, Clark wrote that

“each bicho is an organic entity . . . a living organism, an essentially active work . . . [T]he ‘bicho’ has very defined responses to the spectator’s stimuli” . . . [T]he Bicho “is not composed of still, independent forms that can be manipulated indefinitely at one’s will, as in a game. On the contrary, its parts work together harmoniously as in a real organism, and the movements of these parts are interdependent.”

Like domesticated animals, Clark’s Bicho sculptures exist in a state between manipulable and inflexible, responding positively to human direction but resisting full domination. Made of metal, the Bichos warm quickly beneath human hands, affirming at once their capacity for life as well as their distance from it. Alone, the Bicho is frigid and alien; embraced, it becomes alive. Though there is a tenderness, the participant’s fundamental estrangement from the Bicho is reinforced.

Lispector, too, is interested in the physical manipulation of animals and how tactile intimacy makes the other seem more familiar. This is evident in the excerpt from A Breath of Life, which began this essay, and also in her story “The Crime of the Mathematics Professor,” where a man buries a dead stray dog to atone for the abandonment of his own dog. The man’s heart is heavy as he begins his task—so much so that he feels the need to rest during the burial—but the story culminates in a pleasure reminiscent of how Clark envisioned the pleasure of the Bichos:

He picked up the stiff, black dog, laid it in a depression in the ground. But, as if he’d already done too much, he put on his glasses, sat beside the dog and started surveying the landscape . . . Finally he dropped the shovel, gently lifted the unknown dog and placed it in the grave . . . He covered the dog with dirt and smoothed it over with his hands, feelings its shape under his palms intently and with pleasure as if he were petting it several times.

The mathematics professor “feels [the dog’s] shape” just as one feels the shape of a Bicho sculpture, and with corresponding satisfaction. Afterwards, he begins a heartfelt monologue to the dog he left behind.

In Lispector’s story “The Foreign Legion,” a writer busy at work is consistently interrupted by the little girl down the hall, Ofélia, who consistently harasses the writer. The writer allows Ofélia to hold her new pet, a baby chicken, when she hears its peeping from the other room:

She came back from the kitchen immediately—she was amazed, unabashed, showing the chick in her hand, and with a bewilderment in her eyes that wholly questioned me:

“It’s a little chick!” she said.

She looked at it in her outstretched hand, looked at me, then looked back at her hand—and suddenly filled with an anxiousness and worry that automatically drew me into anxiousness and worry.

“But it’s a little chick!” she said, and reproach immediately flickered in her eyes as if I hadn’t told her who was peeping.

I laughed. Ofélia looked at me, outraged. And suddenly—suddenly she laughed. We both burst into laughter then, a bit shrill.

This moment brings relief and bodily joy to what has been so far a rather tense narrative. As we will see, however, Ofélia’s confrontation with the chick is not over.

Larger beasts seem to bring both artists even nearer to that disorienting and transformative encounter which Clark terms the empty-full and Lispector the it/the thing itself. Lygia Clark’s largest Bicho sculptures, made in 1963, belong to the “Fantastic architecture” group. These bichos tower over the viewer and are made to be awed at rather than petted; they are more beast than critter. They blur the line between the architectural and the organic, the way one might imagine exploring the body of an enormous colossus, and form a more alien relationship to the viewer than her other Bicho sculptures.

For Lispector, too, larger animals suggest something beyond the organic. In her story “The Buffalo,” a woman looks for a beast in the zoo which will incite rage in her heart, searching for something not-animal inside the animal:

The buffalo with his constricted torso. In the luminous dusk he was a body blackened with tranquil rage, the woman sighed slowly. A white thing had spread out inside her, white as paper, fragile as paper, intense as a whiteness. Death droned in her ears . . .

The first instant was one of pain. As if the world has convulsed for this blood to flow . . . Her strength was still trapped between the bars, but something incomprehensible, and burning, ultimately incomprehensible, was happening, a thing like a joy tasted in her mouth . . .

I love you, she then said with hatred to the man whose great unpunishable crime was not wanting her. I hate you, she said beseeching the love of the buffalo.

The buffalo here is seen from far away, the woman removed, by the bars of the zoo, from the intimacy of the mathematics professor’s relationship with the stray dog, or Ofélia’s with the little chick. For both Lispector and for Clark, a smaller animal might captivate a person, but a larger animal becomes a catalyst for fundamental internal change, leading to the abstract, inhuman heart of life.

The Bicho sculptures O dentro é o fora [The Inside Is the Outside] and O antes é o depois [The Before is the After] mark Clark’s pivot to the nonhuman. As Sergio Moya writes in Delirious Consumption, O dentro é o fora

transformed [Clark’s] perception of herself and her body: “It changes me,” she wrote, “I am formless, elastic, without definite physiognomy. . . ‘Inside and Outside’: a living being open to all possible transformations . . . [I]n [sic] its dialogue . . . the acting subject encounters its own precariousness. The subject, like the Bicho, has no self-defining, static physiognomy. It discovers the ephemeral in contrast to every type of crystallization. Space is now a kind of time continuously metamorphosed through action. Subject and object identify each other in the act.”

Here we can see the beginnings of Clark’s conception of the vazio-pleno, or empty-full. Compare Clark’s description of subject and object identifying each other with Lispector’s writing from Água Viva: “I don’t humanize animals because it’s an offense—you must respect their nature . . . I am the one who animalizes myself. It’s not hard and comes simply. It’s just a matter of not fighting it and it’s just surrendering.” For both artists, the animal becomes a vehicle for a kind of desirable nullification of the self.

The corollary to self-nullification is death, which haunts both Clark’s Bicho sculptures and Lispector’s work on animals. In Clark’s case, death emerges as a consequence of how her work has been showcased in the twenty-first century. Clark has by now become an acclaimed and well-remembered artist, but the fame of her Bichos sculptures has ironically killed them: as art objects of history and value, viewers are no longer permitted to hold and manipulate the Bichos themselves. Instead they are encased behind glass, cold and untouchable. In The Experimental Exercise of Freedom, Rina Caravajal offers a fitting lament:

[The Bichos] could be stuffed or exhibited in display cases in museums, galleries, or the homes of collectors, without any suspicion that they had once been alive . . . Taken back to the display case, and therefore to the pedestal, their freedom to live unattached in the world, to benefit from affective intimacy with the largest possible number and variety of others, was pruned away.

These days, museum-goers can only hold replicas. Copies of Clark’s original Bichos are sometimes provided in lieu of the sculptures themselves, as in the Museum of Modern Art’s 2014 exhibition of the Bichos. The original metallic sculpture is never again warmed and manipulated the way Clark expected: the living exchange between the viewer, Clark, and the critter forever deadened by the Bichos’ very reputation.

While the death of Clark’s Bichos is a byproduct of her fame, Lispector’s animals are more deliberately identified with death. In “The Foreign Legion,” Ofélia kills the little chick. The writer doesn’t discover her crime until Ofélia has already left the apartment:

I went back to work.

But I couldn’t make it past the same sentence. Okay—I thought impatiently looking at my watch—and what is it now? I sat there interrogating myself halfheartedly, seeking within myself for what could be interrupting me. When I was about to give up, I recalled an extremely still face: Ofélia. Something not quite an idea flashed through my head which, at the unexpected thought, tilted to better hear what I was sensing. Slowly I pushed the typewriter away. Reluctant, I slowly moved the chairs out of my way. Until I paused slowly at the kitchen door. On the floor was the dead chick. Ofélia! I called in an impulse for the girl who had fled.

Similarly, the unnamed woman in “The Buffalo” commits suicide after she has procured her desired emotion—hatred—from her viewing of the beast. As the woman sinks to the ground, Lispector ends the story:

Trapped as if her hand were forever stuck to the dagger she herself had thrust. Trapped, as she slid spellbound down the railing. In such slow dizziness that just before her bod gently crumpled the woman saw the whole sky and a buffalo.

While the presence of death in “The Crime of the Mathematics Professor” is rather obvious, the buried dog’s status as a replica—for the professor—of the true, abandoned dog is a compelling echo of the Bichos’ historical death. We might consider Lispector’s association of the it with death a matter of redemption for Clark’s Bicho sculptures: the death of the animal as a necessary step in nearing the heart of life.

Austyn Wohlers is a writer from Atlanta, Georgia. In the fall, she will begin an M.F.A. in fiction at Notre Dame.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: