Though every human tragedy has its witnesses, too often those who speak the truth about them are forcefully silenced, whether by censorship, imprisonment, or murder. During the brutal Guatemalan Civil War, the violence and repression inflicted on the populace was felt heavily in the national literature, which saw many great writers suffer in its wake. In this essay, José García Escobar reports on one of the disappeared, the prolific poet Luis de Lión, and his daughter’s poignant search for her father’s lost texts.

Mayarí de León, the daughter of the Guatemalan writer, poet, and teacher Luis de Lión, was seven years old when her father was kidnapped for the first time, in June of 1973. He was kept in prison for eight days.

“When he was released, many of his friends came over,” Mayarí tells me over the phone. “We were living at my aunt’s house in Zone 1, and they came and talked to him.” She also remembers that Ana María Rodas, poet and friend of Luis’s, was there. “She cut a carnation and put it in my hair,” she says.

Mayarí doesn’t remember much else—quietness. Solemnity. Downcast eyes. She was too young and didn’t get to hear the grown-ups’ conversation, and probably wouldn’t even have been able to record more than a phrase in her memory. But she understood what was going on: men had captured her papá. Mayarí claims that from that moment on, she had nightmares. Dreams of ravines filled with dead bodies woke her in the middle of the night.

In 1973, thirteen years into the Guatemalan Civil War, the government and Guatemalan Army often targeted intellectuals and dissidents. Other writers such as Otto René Castillo and Roberto Obregón had been killed already, and many would follow, including Alaíde Foppa, Irma Flaquer, and José María López Valdizón. Then, the thirty-four-year-old Luis was an upcoming literary talent, a prime example of how Guatemalan writers, despite the lack of access to publishers or editors, continued to produce work of high quality. Luis himself, by 1973, had published two short story collections, and his novel El tiempo principia en Xibalbá had received second place in Quetzaltenango’s Juegos Florales in 1972—the first place having been declared void.

“My hands started sweating too,” Mayarí says. “Whenever I’m nervous or excited, whenever I’m taken by extreme emotion, my hands sweat. This started after my father’s first kidnapping.”

Eight days after Luis was taken into custody by the Policía Nacional, he was released. Thanks to the intervention of the Universidad de San Carlos’ student’s association, he was allowed to walk out; Luis had been kidnapped alongside the association’s general secretary. “He came out all bruised and thin,” Mayarí says. “But I know that this first detention confirmed his ideology and social calling.”

Mayarí claims that her father never told her of his days in detention, but she has come to know of Luis’s struggle through his unpublished poems and stories, collected over a search lasting for the last fifteen years. From it stems Luis’s latest publication El papel de la belleza—The Role of Beauty: an anthology of his poetry, which spans from 1972 to the very last poem he wrote before his second kidnapping in 1984. El papel de la belleza, in true de Lión style, shows many of his typical concerns and interests, his militancy and ideology, his attention to social issues and indigenous struggles, his care for the quotidian, his devastating and scenic use of language: minimalistic, casual, relaxed, always elegant.

El papel de la belleza is Luis’s tenth posthumous publication. Luis de Lión was again kidnapped on May 15, 1984. He was killed twenty-two days later.

“Buscando a mi padre, encontré al escritor”

Mayarí was living in exile in Nicaragua at the time of her father’s final disappearance; she was eighteen years old. Three years later, in 1987, her mother gave her a bunch of Luis’s papers. “But I didn’t read them right away,” Mayarí says. “I was terrified. I couldn’t find the courage to open them. I knew my father was missing, and I didn’t know what he had written in those papers.”

Two years later, in 1989, Mayarí finally opened the package. Inside there were seven poems, all dedicated to her, entitled Poemas para el correo—Poems for the Mail, and written in late 1983. “These are very intimate poems, not just because I’m his daughter, but because we shared ideologies. While he was a member of the Communist Party, I was a member of the Communist Youth, and you can see that camaraderie in those poems.”

Here a fraction of one of the Poems for the Mail.

01 (. . .)

my baby girl,

my little comrade

i’d like to send you our dawns and dusks

wrapped in a corncob.

But it would take Mayarí a few more years to begin the search for her father and his work.

Between 1960 and 1996 (the duration of the Guatemalan Civil War), up to forty-five thousand people were disappeared, mainly in accordance with the state’s orders, and carried out by the army and police. This practice increased in the 1980s, targeting guerilla members, union workers, union leaders, student leaders, intellectuals, teachers, priests, and political dissidents—men and women. It is widely believed that many of the desaparecidos were buried in common pits or tossed in the ocean or down volcano craters. Over the years, forensics have found bodies, with clear signs of torture, on former military bases.

Two of the most important findings of recent years are the Historical Archive of the Guatemala National Police and the so-called Diario Militar. The first, found in July of 2005 in an abandoned warehouse in Guatemala City, contains nearly five miles of documents, which include records of police detentions and other human rights violations from 1882 to 1997. The latter, the Diario Militar, found by American archivist Kate Doyle, and made public in May 1999, is a list of 183 people captured and disappeared in Guatemala between August 1983 and March 1985. Each file of the Diario Militar contains, among other things, a photograph of the detainee, the date and exact location where he or she was captured, and often the date of execution. One hundred and eighty-three desaparecidos.

Luis de Lión is on that list.

Luis de Lión is the desaparecido number 135. Luis de Lión was questioned and tortured for twenty-two days. He had diabetes.

Luis de Lión was killed June 6, 1984.

*****

because i know that one day I will die and so will you,

because i wouldn’t want our love to die,

but for a monument to be put in its name

i wish i could write my poems using the highest technology

maybe then they’ll near immortality.

Mayarí finally returned to Guatemala in 1991. She was twenty-five. She admits that as soon as she set foot in the country, she knew she had to look for her father. But what truly sparked her search was the publication of the Diario Militar, which eventually allowed the de León family to sue the state and to take Luis’s case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. To do this, the de León family had to put together a file, show who Luis was, collect his ID, birth certificate, and write testimonies. But just as Mayarí is quick to point out, speaking of the war is still considered taboo in Guatemalan society.

“It took me two and half years to write my mother’s testimony,” Mayarí says. “And it’s only a few pages long.” Mayarí explains that whenever she went to her father’s hometown, San Juan del Obispo, to visit her mother, she would ask her questions about her father. “Sometimes she’d tell me one thing. Sometimes nothing. It’s not like I’d come and tell her, ‘Mama, I’m here to interview you.’ I’d try to ask her things. But she didn’t like to talk about it. She’d contradict herself and quickly shut me off.” Similarly, Mayarí’s brother didn’t like to talk about it; his testimony is only half a page long.

Mayarí sued the state in 2002. Three years later, the then-president of Guatemala, Oscar Berger, acknowledged that the Guatemalan government was responsible for Luis’s disappearance. There was a tribute—and that was that. No body. No investigation. Nothing. But Mayarí kept on looking, eventually coming to focus more thoroughly on her father’s literary legacy.

After she moved to her father’s hometown, she took an interest in Luis’s library. Additionally, her mother welcomed her with a box filled with Luis’s papers. Though both places contained casual things such as receipts, she also found clues of where to look for more of her father’s writing: local magazines and newspapers. Mayarí went to the newspaper archive in Guatemala City and the public university as well.

“I had friends working there,” she says, “so I told them to call me if they found anything written by my father under his artistic name, Luis de Lión; his real name, José Luis de León; or his pseudonyms, Pedro Sicay and Juan del Día.” The poems, then, began coming in from wide-ranging sources.

Revista Alero, La Semana, pamphlets made by unions and student groups, magazines, newspapers. She also found papers sandwiched in between books. Poems written on the back of bus tickets. Poems handwritten beside typed poems—a single typed word was often the seed to another poem Luis wrote, by hand, next to the first one. Mayarí’s mother also had more of Luis’s files. Famed poet and editor Francisco Morales Santos, the engine of one of Guatemala’s first literary collectives, Nuevo Signo, had a bunch of Luis’s poems as well. Turns out Luis, before his disappearance, had explicitly told his wife that in case anything happened to him, she ought to give Francisco Morales his files. “Papa knew he was a target,” Mayarí says.

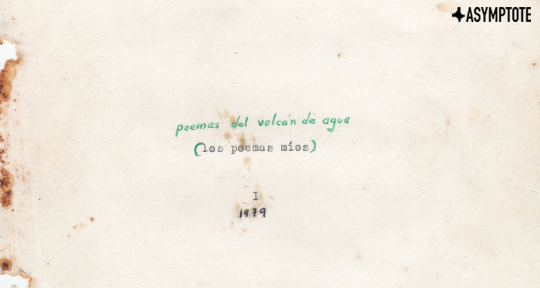

So Paco, as Francisco is known by friends, ended up with dozens, perhaps hundreds of Luis’s poems, stories, written anecdotes, and so on in his archive. Throughout the years, some have been published, including Poemas del Volcán de Fuego and Poemas del Volcán de Agua—both included in this new collection.

“November 2018, we wanted to expand the house, build an extra room for a marimba,” Mayarí begins. “Suddenly, one of the workers told me that they had found a bag filled with papers buried in the garden.” It was Luis’s. When Mayarí rushed to see them, however, rain and the soil’s humidity had sadly turned the documents into a block of paper. Restoration experts told her they were beyond reparation.

“Again, he knew he was a target, that’s why he buried them,” Mayarí says. “In that block of paper, you can see that there was a copy of a newspaper made by Guatemala’s Worker’s Party (PGT).” And of course he knew he was a target—in fact, before his death, Luis’s house had been raided twice.

Another time Mayarí was in San Juan Obispo’s library, taking the books that belonged to her father to start a private collection, when she found a book written in Portuguese. Mayarí was about to toss the book when she casually flipped through the pages and saw her father’s name. “That moment taught me to be extra careful with his things.”

Luis de Lión’s archive seems to be an endless well. Mayarí is quick to admit that she doesn’t know if she has found everything her father wrote, if she’s halfway through Luis’s archive, or if she’s just starting out. And from this never-ending search we were able to receive, in early May, El papel de la belleza. In these poems we can see the writer’s intensity, his ideology, and internal struggles. His poems are casual, musical, personal, and idiosyncratic too. Ocurrentes—witty—also, as seen in his poem the sick one.

the sick one

if your lips were indeed made of sugar

and not simply sweet,

i would’ve died years ago . . .

you know i’m diabetic!

El papel de la belleza

Ediciones Del Pensativo, the publishing house which put out El papel de la belleza, is also Luis’s official press in Guatemala. Starting in 2013, when they reissued Luis’s only novel El tiempo principia en Xibalbá, they have put out two of his collections of short stories (in 2015 and 2016) and another book of poems (2019).

“I’m moved every time I read Luis’s work,” Ana María Cofiño, Pensativo’s cofounder and editor, says. “With his use of tenderness, and with bucolic and everyday language, he’s able to show you the reality and rawness of injustice, inequality, and racism in Guatemala. I feel that all of Luis’s work is both solid and consistent. His work is filled with incisive and beautifully articulated social and political analysis.”

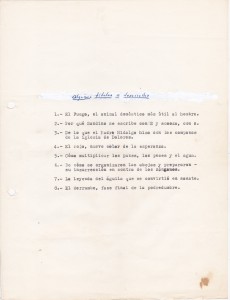

Out of the many boxes and folders and files Mayarí found during her search, some, as you’ve read, were in pretty bad shape. Others looked like they hadn’t seen the light of day in years—perhaps since Luis finished them. She ran into rusty staples, moldy papers, yellowing pages, powdery clips and fasteners, and many documents that looked as old and brittle as ancient papyrus—the book includes photos of some of these papers. And, to Mayarí’s misfortune, sometimes there were up to seven versions for a single poem. “Luis was a very meticulous writer,” Ana says. “A perfectionist.”

Mayarí had to compare each version to find the last one. If Luis, using a pencil, had written a comma in one version, and on the next, there it was, typed down, she knew she was on the right track. But sometimes poems were left unfinished and some, as I’ve mentioned, gave life to a new poem.

“I pity my father,” Mayarí smiles. “I think he had too many ideas in his head. Maybe he was troubled by those ideas.” And this is how El papel de la belleza came to be.

“We had tons of material,” Ana Cofiño adds. “We ended up cutting poems he wrote when he was a young adult. So, when the book starts, in 1972, Luis was thirty-three, and he was a man dedicated to his craft. He was a dedicated writer, but not just a writer—he was a dedicated man as well. He was a father of two, a school leader, and he was very active. I don’t think he had reached maturity as a writer. That would’ve happened after his disappearance. But as a poet, he knew what he was doing.”

Speech to the students in the fifth grade

During this year

despite our broken desks

despite that even the wind keeps an eye on us

despite our malnutrition and ragged clothes

we have learned how to dream

dream like fishes in fraternal and uncontaminated waters

dream in oneself breathing clean air and free of tyrants

dream. And that’s plenty.

“We were hopeful,” Ana María says. “The hippie movement, the rise of feminism, the Cuban Revolution, all of this made us believe that we could build a better world.” A pause. “I never met him. But his words touch me. He’s a true representative of his generation and time.” For the poet Marvin S. García, Luis’s poetry roams in a space bordered by resistance and recreation: “Only a highly sensitive person, someone who’s concerned about improving the conditions which affect him, his family, and community can transform injustices into a flower,” Marvin writes in the book’s prologue. “His poetry is simple, comprehensible, clear, unpretentious; it’s more like an everyday and selfless gift, like the leaves of a plant in the patio of a random house.”

Grandparents

Grandpa Carmen:

wake up,

I want to talk to you,

thank you, grandpa, because without your hand I wouldn’t have known

the miracle of germination,

you taught me how to earn the daily bread with the sweat of one’s brow

you were my tree

and I ran behind your shadow (. . .)

“But at the same time,” Ana continues, “I feel a type of disillusionment in these poems. Just imagine, writing with a vulture on your back! Writing while your friends are getting killed!”

One of these friends was the student leader Oliverio Castañeda. In the late seventies, Luis worked at Guatemala’s public university, USAC, where he met the student leader. On the eve of the anniversary of the Guatemalan Revolution, the self-proclaimed Anti-Communist Army issued a threat against thirty-nine students and union workers, Oliverio included. The operative was called la caza del venado—the hunting of the deer. On October 20 1978, Oliverio was gunned down after delivering his final speech. As a result, Luis wrote the following poem:

about the deer and its hunters

such a long knife to cut a flower,

so many bullets to gun down a flag,

so much fire to burn a book,

such a large shoe to crush the dew,

so much noise to silence one voice,

so many hunters to hunt a single deer,

so many cowards against a single brave man,

so many soldiers to shoot one boy.

Shortly after, Luis was diagnosed with diabetes and was let go from his job in USAC, but kept on teaching without payment. Luis sought to treat his disease using natural medicine. In 1983, due to his condition, Luis began losing his sight. In December 1983, he was no longer allowed to teach in USAC, so he focused on his writing. During that time, he finished a collection of short stories called La puerta del cielo y otras puertas, as well as some of the poems included in El papel de la belleza. In April of 1984, Luis went to his natal San Juan del Obispo to present a puppet show for local kids. During that visit, he buried a bunch of papers in the garden of his old house—the same Mayarí found decades later. By the end of the month, Luis was bedridden. A month later on May 14, 1984, he wrote his last poem, dedicated to Brigitte Bardot, a fraction found here:

And God Created Woman

. . . in the wheat of your body.

Men didn’t make you.

That’s why you’re so perfect.

(. . .)

You were Our Lady. My Lady.

But above all, you were the French Revolution.

Your legs were two love cannons

shooting my eyes and shaking my eardrums.

The very next day, after two weeks in bed, Luis was feeling better. He had been working on a manual to teach poetry to young children and told his son, Luis Ixbalanqué, that he was going out because a friend of his—from Radio Centroamericana—had offered to give him a cassette with classical music. “I’ll be back,” Luís de Lión said. “Don’t touch any of my stuff, because I’m going to keep working.”

Luis went out, got the cassette, and on his way back home, roughly around 5:00 p.m., he ran into a friend, César, who walked alongside him on his way to a drugstore. Suddenly they heard tires racing towards them. Cesar jumped inside a store on the corner of 2nd Avenue and 11 Street. He hid behind the counter. Luis, weakened by his disease, was unable to run. Men, dressed as civilians, put him in a car with no license plates and drove away. According to the Diario Militar, Luis de Lión was killed twenty-two days later.

Tiny Antifascist Tales

They looked for guns.

And they looked, looked, and looked. They flipped the house,

they took its guts out.

And found nothing.

In that house there was not a single gun, only hundreds of books.

Hilarious.

Photos of the manuscript by Hanna Godoy

José García Escobar is a journalist, fiction writer, translator, and former Fulbright scholar from Guatemala. His writing has appeared in The Evergreen Review, Guernica, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. He is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for the Central American region. He works as a journalist in Agencia Ocote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: