With expansive beauty and imaginative observance, Jean-Baptiste Andrea’s A Hundred Million Years and a Day has swept up a enormous amount of praise in its homeland of France, including being shortlisted for the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie française and the Prix Joseph Kessel, and we are now proud to present it to our readers as our Book Club selection for the month of June. Andrea’s story of a man’s hunt for lost creatures pays equal tribute to the earth’s natural wonders and to human persistence and urge for discovery, culminating in a majestic and magnetic tale of what happens when the personal meets the eternal. Within its pages lies a thrilling poetry.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

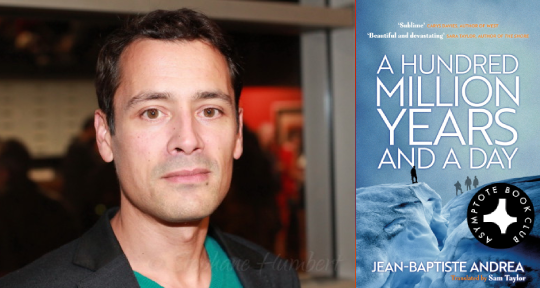

A Hundred Million Years and a Day by Jean-Baptiste Andrea, translated from the French by Sam Taylor, Gallic Books, 2020

Stan, a middling French palaeontologist, is convinced that the skeleton of a “dragon” hides in the belly of the mountains that delineate the porous border between France and Italy. He heard about this dragon years ago, in a second-hand summary of the ramblings of a sour Italian man—the seemingly outlandish contents of someone’s childhood memories. Haunted by this skeleton, Stan drops everything in its pursuit: he quits his university job as a professor, sells his Parisian apartment, and self-finances an expensive expedition to these majestic mountains in the company of his former assistant Umberto, Umberto’s own mentee Paul, and Gio, a taciturn guide for whom the mountains are a second home.

Of course, being a scientist, what Stan is looking for is not really a dragon. From the vague details he has heard, he surmises that the skeleton the caretaker had come across in fact belonged to a brontosaurus—a species that palaeontologists had agreed on being nonexistent, being simply a variation on the apatosaurus. While the book establishes early the love that Stan has for his discipline, for the fossils that he used to meticulously collect and treat as his friends during his lonely childhood spent in another set of mountains, the motives behind this expedition are not necessarily pure. For Stan, having lain forgotten, himself collecting dust in a basement office, this expedition presents his last chance at some glory. If he does find his brontosaurus, proving a theory disputed by palaeontologists for almost a century, the creature will bear his name, articles will be written about Stan, the “animal will give him back his voice.”

I read A Hundred Million Years and a Day in a single, impatient breath. I became obsessed as Stan was obsessed, and every failure, every setback felt incredibly personal. Was that cave in the horizon the one they were looking for? Would they be able to excavate their way through the ice before the warring autumn winds made work impossible? Does the skeleton even exist, or was it all just a fairy tale, the skeleton nothing but an insignificant sack of bones? Abandoned by his companions when all seemed lost and the danger of winter too close, Stan’s thoughts become feverish, his past recollections mixing with the present and infecting the reader as you, too, are no longer certain: what’s real and what is simply an hallucination?

Not that my support as a reader was unequivocal. Like Stan’s comrades, I was often frustrated. Every time Stan went to sleep defeated, certain that tomorrow he would wake up and climb back down to earth and his life, I felt a moment of relief. Only for that relief to be squandered when once awake, Stan thought of some other reason, some other strategy to keep them going. How can one man be so stubborn? What is he trying to prove? But that is the magic of this book—the tug between common sense and the childlike hope that perhaps somewhere, in some forgotten cave in the midst of some unclimbable mountains, dragons might actually exist.

But this book is not simply about the stubborn pursuit of glory. It is first and foremost a celebration of nature, of the grandiose that hides behind what humans’ warped sense of importance considers insignificant. Before he begins his ascent, Stan lies in bed contemplating a fly that is buzzing around his hotel room:

A fly is trapped in the thick air of my bedroom. Sprawled on my bed, I watch it struggle. If it died, if it fell at just the right spot into a drop of resin, if that resin hardened, fossilised and became amber, hard and transparent, if that amber survived a few million years, somewhere safe where it wouldn’t be damaged but not so safe that it would never be discovered, then that fly would, one day in the distant future, deliver to a researcher the secrets of our world. A simple fly that nobody cares about; a simple fly that contains the universe. The fauna, the flora, the sky of 1954, and you could casually smash it with your hand.

This respect for nature permeates the entire book, it’s a respect borne both out of fear and out of awe. It stretches for all beings and all things, from these little bugs to the mountains themselves. Mountains are sacred, godlike, the mountains tolerate this expedition but at one point they also require payment, and that payment may prove to be too high.

It was late at night when I finished reading A Hundred Million Years and a Day. I put the book down, and in the darkness of my room I felt something strange, like that feeling you get after thinking a tad too long about the universe and its vastness. In a sense, this is the kind of mood that Jean-Baptiste Andrea’s writing evokes too, the terrifying dizziness you get when you think about black holes and light years. It’s a humbling, bittersweet experience, a beauty so terrible that you can’t quite bear to be in its presence for too long, otherwise you might lose your mind. Yet, the fact of our insignificance is not really this book’s message. Stan too, at the end, seems to have been driven less by a desire for glory than for a wish to have a good story. It is in our ability to tell great stories, Andrea seems to argue, that our power lies, and this one, indeed, is a great story.

Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in History from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: