Tsotsil is a Mayan language spoken by the indigenous Tsotsil Maya people in the Mexican state of Chiapas and it is in danger of extinction. When writer and translator Shyal Bhandari went to the state for several months to investigate contemporary indigenous poetry, he quickly discovered the poet Xun Betan, who has been fighting hard to keep the language alive in literature. In this essay, Bhandari recounts his meeting with Xun Betan and introduces the pivotal work he has been doing through his writing, publishing, and workshops.

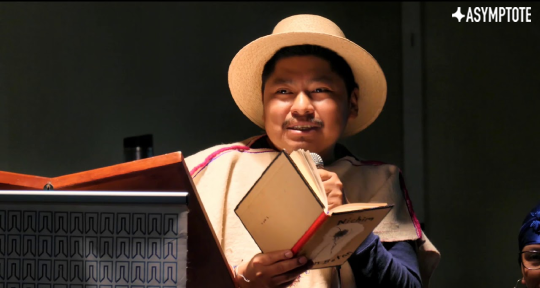

Over the few months that I was in San Cristóbal de las Casas in Mexico, I heard the name Xun Betan brought up plenty of times whenever I asked about contemporary indigenous poetry. “Tienes que hablar con él”—they told me I had to talk with him and that he is involved in many interesting projects, including a poetry workshop for young Tsotsil Maya writers that he runs at his house in the city. They informed me that he is a “unique individual” (in the best sense of the term), almost always to be found wearing traditionally embroidered shirts and his trademark sombrero.

So, when I saw a man dressed exactly like that, smiling and nodding along at the launch event for an indigenous poetry anthology, I thought, “Could that be Xun?” The spokesperson from the editorial Espejo Somos gave him a shout-out, confirming my hunch. At the end of the event, I swiftly approached him about the possibility of sitting down to talk and, to my delight, he suggested coffee the following morning. Anxious to make a good first impression, I arrived punctually, against my nature. I found a well-lit table in the centre of the café and ordered a cappuccino made with pinole (ground-up corn). By the time I had finished my coffee, it was 11:20 a.m. and Xun was yet to show. I was hardly surprised. So, it had to be that at the exact moment I resigned myself to the sobering thought that he had completely forgotten about our meeting, he walked through the door. Naturally, I told him I had only just arrived, hoping he wouldn’t pay much attention to the empty coffee cup beside me. It turned out that we have friends in common. I don’t care if it’s a cliché—the world is a very small place indeed.

Xun was fascinated by the fact that I have Indian ancestry. He hummed me a song in Tsotsil, which reminded me of my grandmother’s morning mantras: “Vayan nene/Vayan olol/Vayan kantsil ol.” Xun explained the importance of recovering the near-extinct Tsotsil prayer, song, and oral tradition with his poetry—only the oldest members of the communities still have the wealth of vocabulary and sophistication of expression in Tsotsil that has been lost to the dominance of Spanish.

Locally, in the state of Chiapas, Xun’s Tsotsil poetry collective Snichimal Vayuchil (Flowery Dream) is a strong force for the promotion of his mother tongue. The collective produces annual anthologies and magazines in Tsotsil as the final product of the workshops Xun leads. The members gather together at Xun’s house to bind their publications by hand with great pride. They are treated warmly in his home, free to come and go as they please, and to borrow as many books as they like from Xun’s impressive personal library. Outside of Chiapas, Xun is a prominent activist for literature in indigenous languages across Latin America. He has translated selected works by the Cuban poet and “father of the nation” José Martí into Tsotsil and has appeared at book fairs, conferences, and poetry festivals across the continent.

We spoke about many other things. He told me about his parents who are small-scale corn farmers from tierra caliente (literally “hot land”), the discrimination he faced at his Spanish-language primary school for being a Tsotsil speaker, and the fact that in order to continue studying, he had to teach himself to read Spanish as a young child, using a copy of The Little Prince as his guide. He began by sounding out the letters individually, then the words, which he slowly made sense of with the help of the illustrations.

After telling me this story, he handed me a copy of his translation of The Little Prince (Ch’in Ajvalil in Tsotsil), which was published in Argentina by an editorial that specialises in collectables. It was a labour of several years that included Xun taking French lessons. The Tsotsil edition felt great to touch, the paper thick and waxy. Every detail had been meticulously thought out. The chapters were written in Mayan numbering and the illustrations had been adapted to a Mayan context. It had been at least ten years since I had read The Little Prince and I couldn’t remember much about it, except that I liked it. I asked him if they keep copies of his translation in local bookshops. He told me they didn’t and that he personally donates the books to bilingual rural schools that lack adequate resources in Tsotsil. It was never his intention to make money from the book. His concern is that the books find a good home and allow Tsotsil-speaking children to read world literature in their own language.

He discussed his community and their rituals, and the innate poetry that lies at the heart of his family’s traditions. For example, the time his sister got married. To ask for her hand, her suitor visited the family home with offerings of cacao and breadbaskets. Only after the third visit did Xun’s parents agree to the marriage. But their blessing was not sufficient for them to tie the knot; the turkeys’ approval was missing. Before the wedding, the godparents of both the bride and the groom must raise turkeys that, by the wedding day will be nice and fat. Then the plucking commences: the bride and groom must pluck their respective turkeys until completely bare. Sometimes a little aguardiente (high-proof alcohol) is fed to the turkeys to ease the process along. With the birds totally defeathered, the couple must let them loose. If after some time, the turkeys remain still, the couple can marry. If they don’t settle (or worse, if they begin to fight), this is understood as a premonition that the marriage is cursed. In such a case, the elders of the community must discuss and advise the couple about whether to continue with the wedding ceremony. I asked Xun what happened at his sister’s wedding: “The turkeys settled down with no problem. A tasty soup was enjoyed by all.”

Just as Xun’s poetry carries the marks of the traditions and rituals of his community, my writing will always carry the baggage of my family history. Xun’s anecdote made me think of Hindu weddings, where the bride and groom, accompanied by their parents, sit around the holy fire. The parents have an active role in the ceremony and they too must feed the fire with rice and ghee. I thought about my grandparents who married in the early 1960s in Delhi. Their marriage was arranged as was (and still is) the normal custom. The families met for the first time at the National Sports Club of India. While the parents discussed the arrangements for the wedding and dowry, my grandfather and grandmother were given the chance to talk in private for ten minutes. He asked her if she would join him in London and she said yes. She liked him; he was educated, handsome and, most importantly, he had kind eyes. I could not help but think that there is poetry in my family history too.

Xun took out more books from his tote bag. They were more “DIY” than The Little Prince, made from cardboard, and hand-bound with coloured ribbon markers: the finished products of the Snichimal Vayuchil poetry workshops he has been running in San Cristóbal over the last few years. He showed me videos on Facebook of his students reading their poems aloud at the pyramids in Palenque. Gathering an audience of tourists (smartphones in hand), they were recording the act of relational poetry. The reading creates a social environment in which people can participate in a shared artistic experience.

Xun and I kept in touch after our first meeting. He invited me to audit one of his workshops with a new group of (mostly unpublished) Tsotsil writers the following week. The group included young men and women from San Cristóbal, as well as several surrounding indigenous communities within thirty miles of the city. Xun spoke of the importance of community elders with regards to the wealth of language they possess, as compared with younger Tsotsil speakers. Xun believes that it is urgent and necessary for members of Snichimal Vayuchil to recover lost vocabulary that has been replaced with “Spanishisms” and to include these rescued words in print. He views the so-called “borrowings” from Spanish as lazy, and a corruption of Tsotsil. “If you cannot think of the word in Tsotsil, ask your parents. If they cannot remember, ask your grandparents. If they cannot tell you, ask the oldest and wisest from your communities,” he implored the young writers. He then challenged the group to think of the Tsotsil word for “chair.”

“Mexa,” (pronounced “mesha”) a young man wearing a Club América football shirt answered.

The Tsotsil “mexa” is taken from the Spanish “mesa.” “This is because our ancestors did not use tables with four legs like the Spanish. The Tsotsil people’s table was not a ‘mexa,’ for it was not four-legged but two-legged. It was not freestanding but, rather, stuck into the ground. It was called an ‘ek’en,’” Xun explained. His approach is defiant of the linguistic dominance of Spanish across Hispanic America. He is realistic about the fact that his mother tongue is close to extinction. He understands that very few monolingual Tsotsil speakers remain, and that almost all of those who possess a rich vocabulary are now very old, hence the urgency. “Ask, ask, ask,” he implores the group, “recover your words and paint with them.”

Xun’s project of recovering Tsotsil language and oral tradition is the foundation of his own poetry. The symbolism of his poems borrows from stories and songs that his parents and grandparents would recite to him in his infancy. He told me that when he writes it is often with an audience in mind, namely, the future generations of Tsotsil speakers. He is a proponent of popular poetry that is rhythmic and musical, where imagery from nature and the landscapes of indigenous communities feature prominently. At the end of the workshop, Xun handed out a number of the carboard, hand-bound volumes of Snichimal Vayuchil’s annual bilingual (Tsotsil-Spanish) poetry journals from the last few years and invited the group to each read a poem. I read one of Xun’s poems (“Sacred Ray of Light”) that I later translated into English:

Fly, boy, fly

to the sacred green trees climb

for you are the protector of Mother Earth

the sacred spirit of white corn.

Fly free feathered bird

sing with your sisters the flowers.

Dance around with the sacred clouds

for you are the shimmering of sacred rain.

Shyal Bhandari is a London-born writer and translator. He studied Philosophy and Spanish at the University of St Andrews where he was a recipient of the Royal and Ancient International Scholarship for his project translating poetry in indigenous languages from the south of Mexico to English.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: