The journey that a language takes to arrive at us is often unimaginably intricate, with all the marks of history, people, and land upon it. In the following essay, gorgeous with lyricism and intimate with the facts and ideas of past and present, Maya Nguen takes us through the emotional and physical cartography of Vietnam and its language, and how such structures reverberate against the ever-mutable definitions of identity, personhood, and home.

In the beginning is a creation myth.

Âu Cơ meets Lạc Long Quân where mountain meets sea.

They form a bond and Âu Cơ bears an egg sac with a hundred children.

At the core of their bond with one another is another bond of one with the mountain and the other with the sea. So it came to be that fifty children followed Âu Cơ for the mountain whence she came and fifty followed Lạc Long Quân for the sea whence he came. And as Âu Cơ calls for land and Lạc Long Quân calls for water their children come to call a country

land water

đất nước ¹

where land begins at the edge of the water that starts at the end of the land: is a shore that holds the country in the crossing between one word and another: between 越南 & Indochine Française & Việt Nam & Vietnam

the Vietnamese language emerges at the border

thoroughly other & utterly ones own

& defined by a border endures

Diasporic

& Pure

<< >>

In prehistory: Austroasiatic tribes living in the Red River Delta (today’s Northern Vietnam) speak a Proto-Viet language belonging to the Mon-Khmer language family.

<< >>

Beginning in 111 BC: Colonization by the Chinese empire for eleven centuries to follow. Classical Chinese is imposed as the written language of the government elite, forming the basis of politics, science, and literature. Proto-Viet continues to be spoken, and its speech, to be influenced by Classical Chinese.

<< >>

Beginning in the tenth century: Independence from the Chinese won by King Ngô Quyền at the shores of Bạch Đằng River. After a millennium of foreign occupation without a formal writing system of its own, independent Vietnam continues as before: with Classical Chinese at its helm.

<< >>

Beginning in the thirteenth century: A vernacular written script called Chữ Nôm (lit. “southern characters”) is developed on the basis of Classical Chinese to record Vietnamese folk music and poetry. Considered as the pillar of Vietnamese literature, Truyện Kiều (Tale of Kieu) by Nguyễn Du is written in Chữ Nôm. For this script, Chinese characters are naturalized to fit the Vietnamese spoken language, which itself includes Chinese words naturalized into Vietnamese. “Southern characters” in Chữ Nôm: 𡨸喃. “Southern characters” in Classical Chinese: 字南. 𡨸喃 is taught in reference to 字南. 𡨸喃 exists alongside 字南: forming a pillar: a porous border.

<< >>

Beginning in the seventeenth century: Portuguese missionaries devise a Romanized script based largely on the Portuguese alphabet to aid their learning of Vietnamese. Instead of learning Classical Chinese, they decide that the Vietnamese language needs a different access point. With the publication of Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusinitanum et Latinum (Vietnamese—Portuguese—Latin dictionary) by a Jesuit lexicographer Alexandre de Rhodes in 1651, another border begins to emerge.

<< >>

Beginning in 1887: Vietnam is colonized by France and given a French name Indochine. For the French to define Vietnam as an indeterminate landmass between India and China is to undermine it: is to contribute to a crisis of definition: a state of emergency: a space for the Vietnamese language to defy through that which is meant to undermine: is to be determined despite the indeterminate: is to fight to call a language mine.

<< >>

Hồ Chí Minh presents Demands of the Annamite [Vietnamese] People

to the League of Nations in 1919

in French.

<< >>

Instead of imposing a new order onto the centuries-old Vietnamese order, the French graft themselves onto preexisting structures of Vietnamese government and society. There are three preexisting structures that intertwine at the core of the Vietnamese Language: Chữ Nôm in use for five hundred years: Classical Chinese in use for two thousand years: and the Viet language in use since pre-history.

<< >>

Hồ Chí Minh writes over a hundred poems in his Prison Diary

while held captive in 1942

in Classical Chinese.

<< >>

The French follow the lead of the Portuguese in interpreting the question of the Vietnamese language on their own terms—by extricating Vietnam from its East Asian cultural sphere of influence. Not the birth of an independent Vietnam, but the arrival of a competing foreign country, triggers Vietnam’s turn away from its millennia-long Chinese lineage. To fill the gap created by a language severed from its ancient written form, the French turn to the largely neglected system of transcribing Vietnamese via Latin. This—the result of the French battling the Chinese over control of the Austroasiatic Viet sound—is the emergence of the modern Vietnamese language.

<< >>

Hồ Chí Minh declares independence

for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945

in Vietnamese.

<< >>

Chữ Quốc Ngữ (lit. “national script”) is made up of twenty-nine letters of the Latin alphabet and nine diacritic marks to signify tone and to create additional sounds. The tautology of a national script self-described as a national script is a reminder that the Vietnamese language cannot be taken for granted. It is the only culturally East Asian country that uses a Latin alphabet. However, this alphabet is not as the Latin alphabet is for Portuguese, or as the Cyrillic alphabet is for Russian, but it is, distinctly, a national Vietnamese script.

To fully embody the Vietnamese sound, the Latin alphabet must be significantly marked to increase its expressivity. Equipped with only twelve vowels, the Latin alphabet evolves in order to express the sixty vowels used in Vietnamese: It gives shape to the sound that pushes it to sound different.

From o to ô: from meaningless vowel to umbrella.

From ô to ổ: from umbrella to nest.

These vowels nest in their sound a set of colonial marks

atop a set of colonial marks:

These same vowels set the tone, the rhyme, and the emotion of a song:

Đường vinh quang xây xác quân thù . . .²

<< >>

Beginning in 1910: Classical Chinese is replaced by Chữ quốc ngữ as the official language for all public documents in Indochine. To consolidate their influence on the Vietnamese language, the French begin teaching Chữ quốc ngữ alongside Française. For the Vietnamese educated youth of 1930s, the first written language is French, and the second written language—their own. The spread of the written script exponentially increases with France’s introduction of a wide-spread system of elite schools. Since most of Vietnam at the time is illiterate, the spread of an education system becomes synonymous with the spread of Chữ quốc ngữ.

Colonial oppression is a state of emergency for Vietnam: France replaces China as the control valve of the Vietnamese language: Chữ quốc ngữ is introduced as an enforced intervention devised by the Catholic Church and deployed by the French government, not to forge a path for Vietnamese self-determination, but to make it all the more difficult.

A state of emergency for Vietnam is the emergence of its nation-state: The spread of print material increases literacy rates of Chữ Quốc Ngữ, which swiftly morphs into a tank for Vietnamese expression, mobilized by a new generation of Western-educated intellectuals ready to repurpose French republican notions of độc lập and tự do³ against the French:

“The liquidation of illiteracy is actively undertaken.

[. . .] people who were freed from illiteracy [. . .]

Illiteracy was wiped out [. . .]”

— Hồ Chí Minh, 1952

In reaction to the swift turn of events, the French push the Vietnamese to revert to values of Confucianism, monarchy, and civil obedience from which they themselves had forced the Vietnamese to detach just a century before. But this is not enough to stop the spread of Vietnamese-mobilized mechanisms of the press, the written script, and the language of liberation. In 1945, Hồ Chí Minh goes on to declares, as did Ngô Quyền in 938 AD, an independent Vietnam. Only this time, Vietnamese independence comes with a united spoken and written Vietnamese language.

<< >>

Beginning in 1955: Second Indochina War: or Resistance War Against America: or Vietnam War: or Sacrifice and Survival of the Vietnamese language. With Vietnamese independence secured, so too is its sound and script. But crisis continues from the border with other nations to the border within one’s own: from facing a storm from outside to embracing the other side from within.

Along the border bisecting Vietnam, language splits into proletariat propaganda to the North, and free press to the South. Before this rift can harden, a short period of openness ensues, during which two journals—Nhân Văn (Humanities) and Giai Phẩm (Masterpieces)—spring up as platforms for open criticism of the Communist Party. Led by poet Trần Dần, these journals become the only instance of widespread intellectual dissent ever to occur in North Vietnam.

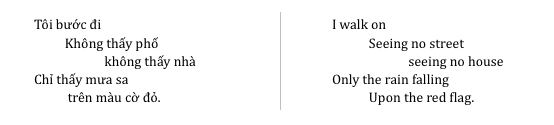

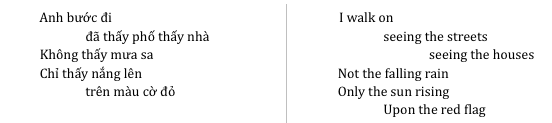

After just three years, the movement collapses under government persecution. Trần Dần is imprisoned and forced to undergo self-criticisms. In “Nhất định thắng” (To Certain Victory), a poem written during his self-criticism period, Trần Dần’s line is forced to fall in line with party rhetoric.

No sooner than the words expressing the grim conditions of the North appear . . .

. . . does the cheer of Communist propaganda make them swiftly disappear:

The Communists draft the Vietnamese language in their fight to unify the country, to achieve certain victory over the border, that is, to eradicate it altogether.

<< >>

The day April 30, 1975 is known as the Fall of Saigon.

The day April 30, 1975 is known as the Liberation of Saigon.

That day Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

<< >>

Beginning in 1975: The Communist Party of Vietnam takes over from the French who took over from the Chinese as the control valve of the Vietnamese language. All press becomes state-owned, either wholly or partially. Some writers turn to publishing work abroad. Others move abroad to save the other side of the Vietnamese language.

<< >>

The war between North Vietnam, South Vietnam, United States, France, Soviet Union, China, Laos, and Cambodia forces a far-flung diaspora into emergence:

“So the next time someone asks me if I’m really Vietnamese . . .

stranded between two languages so as to always appear to one as coming from the shore of the other, the diasporic existence is not defined by one or the other, nor by one and the other, but rather by a crisis of definition: a constant emergency of emergence: a rejection of what is peacefully called a language:

. . . I’m going to say ‘yes and no,’ . . .

a sustained precarity at the border sustaining the possibility of other orders: a space between đất (land) and nước (water): the shore as the space at the core of Vietnam: the shore at the core: is the diasporic lineage of the Vietnamese language:

. . . and then I will wait for them to ask me another question”⁴

with roots in the furthest diasporic shores: with seeds dispersing new relationships to language that with each ship push the border of language ever further: into a formal border attached to no particular shore, ship, or seed, native or overseas: into the border as the form of Vietnamese.

<< >>

Diasporic life is un-firm, with no stable home, thereby able to shift settled ground, to un-firm it. There can be no firm diasporic life. Only affirmation of the un-firm: the resolution of irresolution between one home and another. Only then is it possible to hone in again on home, in high resolution.

I used to visit my grandparents in Vietnam every summer, and every summer the homecoming feast would grow more extravagant, as if to mark the increasing distance between my two homes. The warmer the welcome “Make yourself at home!”, the more I felt I was somewhere other than home. Every summer, I would grow familiar in it as though it were my own. But in the end, no matter how familiar it became, my home remained in the as though:

between one home and another

home as though home

A diaspora at a distance from home makes of a disadvantage a vantage point, a chance to step back so as to see more clearly. For to look inside is to look from the outside in: from the border in the core: first other, then home.

From the Chinese word for country, 江山 (river mountain) comes the Sino-Vietnamese, sơn hà (mountain river) and the Vietnamese, đất nước (land water), until eventually, as when one looks at something long enough for it to look strange again, đất :: nước appears with its opposite parts drifting apart, long enough for the eyes to adjust to a view with two sides.

As the distance between the two sides grows, the crisis of definition at the border becomes the very definition of a new order: a Vietnamese language with a porous border. Vietnamese is a language with a history of being made a home, and a diaspora that is this history in the making. For since the beginning, the Vietnamese condition has been a diasporic condition.

<< >>

An island to the eye is land, and to the ear, an eye-land.

I land on an island, tripping over land stirs under emphasis shifts.

Đất grows, uncertain of its border with water.

Land grows uncertain of its border with nước.

Mouths twist with the effort to withstand,

To drink the water not the salt.

But there is no clean water to be found

But sea and land, water and sand,

Country and đất nước.

- đất nước is Vietnamese for country. đất means land. nước means water.

- From the Vietnamese national anthem, roughly translated as: The road to glory is built on the corpses of enemies.

- Independence and Freedom, respectively, from Ho Chi Minh’s famous phrase: Không có gì quý hơn độc lập, tự do (There is nothing more precious than Independence and Freedom).

-

Quote from Viet Thanh Nguyen’s blog.

Image credit: Nguyễn Trinh Thi, from Landscape Series #1 (2013).

Maya Nguyen (b. 1996) is a Vietnamese-Russian interdisciplinary artist working at the boundaries of sound, text, and image. Her work excavates the power relations inherent in human interaction and the environments that facilitate these interactions, such as the domestic sphere, the colonial subject, or border zones. She is the assistant poetry editor of Asymptote Journal, holds a BA in Philosophy and Comparative Literature from the University of Chicago, and is an MFA candidate in Sound at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. https://soundcloud.com/maya_nguyen

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: