Our second feature for Asymptote at the Movies is Andrei Tarkvosky’s Solaris, a 1972 Soviet masterpiece based on Polish writer Stanisław Lem’s 1961 novel of the same name. Arguably one of the greatest science fiction films ever made, the plot focuses on psychologist Kris Kelvin and his arrival at the space station orbiting Solaris, a planet whose ocean had been the focus of intense scientific study for decades. As the two other scientists aboard behave increasingly strangely, Kelvin discovers that they are being “visited” by figures of their past, resurrected in the space station. A complex exploration of man’s place in the universe, his quest for knowledge, and the meaning of love and life, Solaris is a triumph.

Sarah Moore (SM): Sometimes it appears that a novel exists, destined for a certain filmmaker, as if it had in fact been written for such a connection. So it is with Lem’s novel and Tarkvosky; Solaris lends itself perfectly to Tarkovsky’s slow, profound meditations on human nature, the purpose of existence, memory, and the function of art. Lem’s novel is classified as science fiction but (as with many works of science fiction) incorporates a wealth of philosophy and spirituality. Tarkovsky unabashedly confronted the big questions. His films are not designed to entertain—their pleasure comes from the possibility of being forever changed by seeing them. Both the novel and the film are immensely detailed; whenever I watch Tarkovsky’s film, I am always struck by how much there is to comprehend, how much more there is to be contemplated each time. Perhaps a good place to begin this discussion, therefore, is with Tarkovsky’s own impression of Lem:

When I read Lem’s novel, what struck me above all were the moral problems evident in the relationship between Kelvin and his conscience, as manifested in the form of Hari. In fact if I understood, and greatly admired, the second half of the novel—the technology, the atmosphere of the space station, the scientific questions—it was entirely because of that situation, which seems to me to be fundamental to the work. Inner, hidden, human problems, moral problems, always engage me far more than any questions of technology; and in any case technology, and how it develops, invariably relates to moral issues, in the end that is what it rests upon. My prime sources are always the real state of the human soul, and the conflicts that are expressed in spiritual problems.

Tarkovsky’s preference for the human problems over the technological is clear in his huge re-structuring of the plot—or rather, his ability to lengthen the chronology. Whilst the action of Lem’s novel is restricted solely to the space station, such action contributes only three-quarters of Tarkovsky’s film. In a forty-minute prelude, the day before Kelvin’s departure to Solaris, we see him at his parents’ home, surrounded by lush nature. Long sequences of forests, flowing streams, underwater reeds, and large ponds contrast with the sparse, sterile settings of the space station that will appear later. Here, his complicated relationship with his father is introduced and he burns documents over an outside fire, preparing for a total rupture from his life on earth. For a text that so explicitly posits the choice between remaining on Solaris in the pursuit of scientific study and returning to earth, beginning the film in such a naturalistic setting is a huge gesture that places the human at its centre. How do you feel about the tension between “the scientific questions” and the “hidden, human problems” in the film?

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): The first part of Solaris is perhaps my favorite—so tentative in sentiment and so otherworldly in imagery, it seems intent on probing the sensuous human world with the abstract awareness and curiosity of an extraterrestrial. There was something unearthly in these scenes—the occasional overwhelm of white noise, the sudden pivots of the camera, the strange, stuttering interchanges of dialogue. That glorious scene in which rain suddenly falls in sheets, overtaking the senses—there proved to me a distinct hierarchy inscribed between human and inhuman forces, and how incongruous our world can be in such moments where we are dominated, even temporarily, by our surroundings. As Lem says in the book, “We all know that we are material creatures, subject to the laws of physiology and physics, and not even the power of all our feelings combined can defeat those laws. All we can do is detest them.”

Whereas the book perhaps parses some sort of dichotomy here, between the scientific and the human, I feel as though Tarkovsky’s cinematic language disrupts this tension, as you say, in order to more pointedly investigate scientific pursuits as humanistic investigations—namely, we are our own curiosities, and what we seek to know about the outside world is not its function or intention, but what our role within it is. As Dr. Snaut, one of the scientists on board the space station, says: “We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors.” It is the overlap of morality that elapses over an exploration into the unknown, and it is ultimately our moral limits that we (ought to) surrender to, not our physical limits.

This capacity to humanize is—excuse me as I indulge in tautology here—a quality that is irreducibly, and singularly, human. So there is no other way to explain the central phenomena of Solaris besides our language, and our understanding, and our moralities. In adorning it with this definition, then, its discoverers (or perhaps are they victims?) are able to claim some sort of dominion. That, to me, seems to be the central tension of this film—the function of knowledge and its assumed ability to allow the knower some sort of ownership, a conceit that swallows our philosophies.

Another thing that I noticed within the disruption from page to screen is that Stanisław Lem’s language in the novel has an insistence on telling that the cinematic format cannot comfortably imitate—but where he favors narrative, Tarkovsky, as dictated by his medium, probes the emotive consequences of images. I’m not sure if this indicates more of an interest in human matters, but perhaps just a very fine, precise directorial effort to parse with images all the content and emotional weight within even a few lines of text. Language was invented to serve human purposes, but images were not—they just always were. So when one creates intent with images, the pace, strategy, and concentration of looking has to be much more carefully structured. In this film, the actors perform the act of looking with such intensity, that the viewer can’t help but follow their example.

SM: Yes, I absolutely agree that Tarkovsky is able, as you say, to probe the emotive consequences of images. Lem’s novel is filled with extraneous texts—texts that are known, referenced, or read by Kelvin as he makes us aware of the over-abundance of theories that have been produced through decades of Solaristic research. These studies are condensed in the prelude of the film: Kelvin and former cosmonaut Berton watch the tape of a testimony that Berton himself gave, years previously. Berton insists that he saw the appearance of a child—absurdly twelve feet tall—on the surface of Solaris. In Lem’s novel, Kelvin reads the transcript of the interview whilst Tarkovsky is able to visualize this, as part of Kelvin’s memory. For Lem, Berton functions as a scientist who has previously experienced the strange phenomena of Solaris, but was discredited for recounting such an experience. For Tarkovsky, this minor character of the past is given a larger, active role. It is tempting to think that what may have drawn Tarkovsky quite so much to his character is the image of what he saw: a child in an enlarged form. Children often play pivotal roles in his films—Ivan’s Childhood most obviously but also, for example, the final scene of Stalker, in which a child seemingly moves a glass by fixing her eyes on it. Moreover, the scene then continues with Berton leaving the house and driving down a long, urban motorway with his own child in the backseat. The film is abundant with similar flashbacks that use monochrome, sepia, and color to great effect. The linear action of the novel is therefore condensed into Kelvin’s own memory. Tarkovsky has famously spoken of the particular ability of cinema to portray time:

The image becomes authentically cinematic when (amongst other things) not only does it live within time, but time also lives within it, even within each separate frame.

This inner time enables reality to be constructed (and limited) by one’s own consciousness. Memories continue to flood the present and gestures—the scene in which Kelvin kneels and embraces his father at the end, for example, contain within it the initial scenes with his father and the same embrace he made towards Hari. Tarkovsky articulates that we really create each other, out of our emotions.

XYS: That’s a really beautiful way of putting it, Sarah, that methodology of inventing the other people to populate a world that is, centrally and separately, ours. The enigmatic figure of Hari really nails that synecdoche for me, her enchantments inextricable from her gradual disintegration, and how attentive Kelvin becomes to the way she reacts to things (despite the “knowledge” that she is a manifestation of his conscience), as if her sentience only further evidences his ownership of her—as she becomes more “real,” she also becomes more capable of being possessed.

The treatment of time, and of memories instilling their way into the present, perhaps resonated less with me—I somewhat resented the narrative jargon of recall-replay, perfectly operative in text but somewhat stilted on the tongue. This postulation of Hari being “new” to the world, and therefore reliant on a system of instruction in regards to how to be herself, undermined her self-inflicted demise, after the deluge of memories and self-awareness ravage her.

What really worked for me, however, was Tarkovsky’s enactment of betraying the memory of someone. We say that all the time, with the understanding that new knowledge surges backwards to corrupt the old. Hari, in living memory, now has the capacity to both perpetrate and respond to that betrayal, and the ever-present tension and concern between her (so brilliantly acted by Natalya Bondarchuk) and Kelvin is constantly in reference to that threat. The fact that Hari can experience tremendous physical pain, yet heal—and for this film to show such scenes with the viscerality and brutality that they do—indicates a rejection of that idea. The cruelties that occur never escape the present; in this timeline, there is no betrayal of memory.

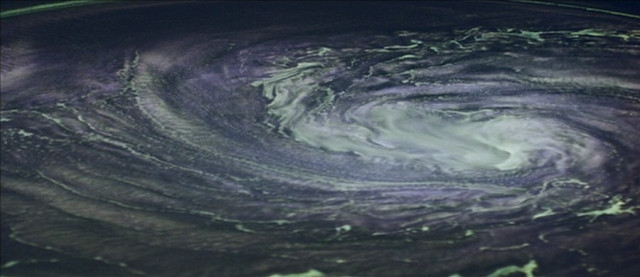

SM: Earlier in the prelude, a very short scene shows Berton’s child meeting a young girl, presaging the relationship between Kelvin and Hari. Whilst the relationship between them is prominent in Lem’s novel, it is nothing like the love story this relationship becomes in Tarkovsky’s film. In fact, Tarkovsky’s Solaris is arguably more a love story than a science fiction film. As Sartorius says to Kelvin, “Except for your tryst with your ex, nothing here seems to interest you.” Tarkovsky is always concerned with the power of love, and Kelvin’s relationship with Hari expresses the continual reiteration of the failure of love—this leads to a consideration of repetition, which I think is more enhanced in the film than the novel, and finds its ultimate manifestation in the film’s wonderfully enigmatic ending. The sets also instill a feeling of repetition. Almost all of the rooms are circular, the windows too. Tarkovsky’s hallmark use of mirrors is everywhere. Cynical of the pursuit of scientific inquiry, Snaut says, “We don’t want any more worlds. Only a mirror to see our own. We try so hard to make contact, but we’re doomed to failure.” Being haunted and drawn back to the past is a major theme of the novel, of course, as the “visitors” that Solaris’s ocean produces are ghosts of each scientist’s past. Yet this is balanced with the pursuit of scientific progression in the novel. In Tarkovsky, the draw of the past is almost the sole focus; the frequent wide shots of the ocean as an immense, swirling organism create this sense of life as a whirlpool, continuously pulling us back into certain, formative, inescapable memories. For Tarkovsky and Kelvin, these memories are relationships—with Kelvin’s wife, Hari, his mother, and his father. After Hari’s first appearance on Solaris, ten years after her actual death, her multiple resurrections and the impossibility of her destruction further underline this repetition.

Much of the scientists’ conversation, and even Hari’s own concerns, question to what extent she can be human, her own agent, or merely an expression of Kelvin’s consciousness. “I don’t even know who I am anymore. Who am I? Do you know who you are?” Hari asks. “Yes, all humans do,” Kelvin replies. Yet Kelvin doesn’t know who he is. The entire film follows his quest for self-understanding.

I think Tarkovsky allows Hari moments of powerful insight into the workings of human nature. Sometimes she even seems to function as the aforementioned mirror, held up to reveal the shortcomings of Kelvin and the two other scientists’ understanding. “No, that’s not the point. It doesn’t matter why a human loves,” she says. She doesn’t seek a “point” or an objective; she doesn’t seek an answer to the question of love, in a film about man’s hubris and a Faustian quest for immortality. “You’re all very human, but each in its own way. That’s why you’re quarrelling,” she continues. She is clumsy and she allows for human imperfection. Sartorius may describe her as “a mechanical repetition of the form! A copy from a matrix!” but how do you feel Hari is portrayed in the film? As a figment of Kelvin’s consciousness, unable to exist outside of him? Or as a woman imbued with a growing humanity and understanding?

XYS: Lem wrote: “. . . no one could stand outside himself in order to check the functioning of his inner processes.” But there Hari is, pointedly averting the way Kelvin chooses to remember her, fiercely subjugating the woman she was when she was alive. That she is the only one to perform blatant displays of emotion—distress, pain, sorrow—as opposed to the three scientists on board, who themselves indulge in dissertation and jaded submission, seems a very intentional directorial choice; Lew writes these characters with impassioned distinction, but none of this really comes across with the exception of Hari (perhaps attributed to Soviet stoicism?).

Tarkovsky achieves a great victory here in his portrayal of death: Hari’s resurrections, and how uncomfortable they are for the others. It probes the question—what is human if not the capacity to bear human consequences? As to your question, she is both and neither: she is a relay of Kelvin’s memories and yet, imbued with a human form, she is inevitably incumbent with the attached capabilities, and frailties. Yet she does not possess that one quality I mentioned earlier—that inescapable tendency for compassion, which, crossed with love, leads inevitably to the desire for possession.

Though she enacts death—the ultimate consequence, she does not have the consciousness to suffer it truly. One can argue that the true acknowledgement of consequence is not simply an informed prediction (or fear) of the future, but our ability to project ourselves into the future to receive that consequence, as our present self, one with our future self. Hari is not inculcated with this sense of projection—seeming to experience her self as separates—and cannot therefore be said to be entirely at the bearing of such knowledge.

That imagined things may take on a life of their own is perhaps our very greatest fear; it is perhaps the most commonly explored trope of science fiction. When Akira Kurosawa watched the film, he described being “in agony with a longing to returning to the earth as quickly as possible.” I felt a similar sense of trepidation throughout my viewing—there was an aching sense that humanity was being performed, not in the way of actors acting, but in the way of a more sinister mimesis, one imitating the habits and behaviors of oneself.

SM: One final point I want to discuss is Tarkovsky’s mosaic use of multiple art forms in the film. Firstly, there is the repeated theme of Bach’s Choral Prelude in F minor. Then, the use of Bruegel’s painting “Hunters in the Snow” which the camera pans over in slow shots. This is reminiscent of the end of Andrei Rublev, in which the camera pans for eight minutes over Rublev’s actual frescoes, turning, after three hours of black and white, into color. And Tarkovsky also uses this same Bruegel painting in The Mirror two years later. It is a wintry scene, depicting an unsuccessful hunting expedition. Whilst depicting hardship and failure, the scene is still comforting in its portrayal of a community, shared labor, and warmth from fires. In addition to Bach and Bruegel, the film is scattered with references to Dostoevsky, Cervantes, Goethe, Luther, and Tolstoy. The layers of scientific Solaristic studies in Lem’s novel transform into the history of artistic endeavor in Tarkovsky’s film. What do you make of these allusions?

XYS: The sum of the allusions can all be said to complicate the depiction of the alien as entirely out of the human realm—the nesting tendency. The room in which the Bruegel paintings hang is also at a direct contrast with despair and the rest of the desiccated space station—it is an elevated space, painted in deep and contemplative colorings, intended to provide some intellectual grounding to the personalities, at a loss outside of their typical environments

Going back once again to the central question of humanity, I feel as though in this film, there is a focus on the constructing factors of the soul, and in this room in particular, it is explicit that a soul is one who takes part in existence communally, actively as part of the world, and capable of understandings that are greater than oneself. That maybe, feeling human emotions and practicing human patterns, is not sufficient. Kelvin reads the passage from Don Quixote, which states that sleep “closely resembles death”—the division is there. Sleep is not death. Hari has learned to sleep, but she has not learned to die.

SM: In a diary entry from January 13, 1972, Tarkovsky lists thirty-five comments and criticisms made by various Soviet committees after hearing his plans for Solaris. He is exasperated and unwilling to comply with their changes. Number thirty-five of their comments is as follows:

35. Take-home message: “There’s no point in humanity dragging its shit from one end of the galaxy to the other.”

“I might as well give up,” Tarkovsky concludes. Luckily, he didn’t. He finally negotiated with the Soviet authorities and released the film later that year. The take-home message, if there is one, is as ever changing, unfathomable, and breathtaking as Solaris’ ocean.

Sarah Moore is a bookseller and editor from Cambridge, UK. She currently lives in Paris and is an Assistant Blog Editor for Asymptote.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor, born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her poetry chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was the 2018 winner of the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize. She currently works with Spittoon Literary Magazine, Tokyo Poetry Journal, and Asymptote. Her website is shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: