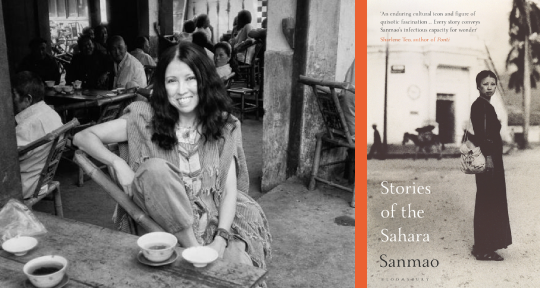

Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao, translated from the Chinese by Mike Fu, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020

One of the most beloved characters for most Chinese children born after 1940 is the infamous Sanmao (三毛 / Three Hairs), an orphan so impoverished that he could only manage to grow, well, three hairs. Set largely in nationalist Shanghai, the narrative of Sanmao detailed his nomadic wanderings, often involving ignominious miscarriages of justice, teetering hunger, and desperate, one-yuan schemes. Round-headed, ribcage-baring, picking up cigarette butts on the street, Sanmao was adored by children like myself—poor but not destitute, bred with an uncertain yet determined idea of the world’s cruelties—cultivating a helpless, weary sort of empathy for a two-dimensional friend.

It’s strange that we live in the age of Crazy Rich Asians, because our formative stories are still about paucity; in a history defaulting on need, not enough time has passed to allow for much of anything else. Wealth, burdened by its relativity, has meant that compassion for the less fortunate simultaneously served to stoke flames of aspiration. The age inoculated with the pathos of Sanmao is characterised by a fierce survival instinct, one that breeds a sharp protectiveness and a craving for stability. There is no doubt in my mind that my mother handed me a copy of The Wanderings of Sanmao in hopes that she was in the process of raising the next foremost cardiac surgeon, saved from a life adrift. It is a wonderful anomaly, then, that one of the greatest literary wanderers in the Chinese language chose to take on Sanmao’s name for her own, overpowering his numinous survival with her own, insatiable desire for the extraordinary.

Sanmao, the nomadic Taiwanese writer, has stormed her way into the English language with the travelogue that defined her restlessness and raw talent for narrative: Stories of the Sahara, now appearing via the dedicated and sensitive translation of Mike Fu. In 1976, when Stories was first published, Chiang Kai-shek had just died the previous year. The Kuomintang, steadfast in its late leader’s convictions, vowed to never compromise with the Communist mainland. There were children and adults who had never lived in a country free of martial law. This book—unleashed and contrary, occasionally jubilant and startlingly present—was to a starved populace an elixir. The world, bound and weakened, was all of a sudden at one’s fingertips.

1973: Sanmao answers a call from the Sahara. Her lover José had taken a mining job in the Spanish-occupied region of the desert, and he was ready for her to join him. She arrives in El Aaiún and the days begin—days that would become years, drastic and panoramic years in both geographical and emotional survey. The Sahara is uncontainable, and so is she. The stories, told with the quick-hand of someone torn between the eagerness of telling and the compulsion for leaving, make up a psycho-topography of interior travel. Arguing with neighbours, peddling fish on the streets, escaping the hands of vicious men, taking a driving test, suffering a cursed stone, witnessing the inseparable duality of love and cruelty—the woman and the desert devour one another.

Of her nearly twenty books, Stories of the Sahara is perhaps the least contemplative, and most exuberant. Writers keep journals to reform the world into a place of their own; between the margins of a text, retelling completes the phenomenal trajectory of being into knowing. The process of writing—its linearity—defies the disorientation of the body, strained by memory but anchored in time, and as such, we do not read journals simply because we are curious about the stories within them; it is the intensification of experience that is fascinating to us. Stories of the Sahara is a relic of imperfect passions, of individual design that shamelessly centralises the self. The infinity of her environment is elaborated by her architecture, and her first-person ensures vivacity by never adjusting herself to standard; she is so often reckless, petulant, naive, and emboldened by the idea that there are no consequences to her actions, perhaps because she has no obligations to the land. Closing the book, we are not left with the knowledge of what it was like to be there, in the Sahara. Instead, we have the certainty that she was there.

The woman’s journey is often an anxiety of identity, a warring of body politics and self-consciousness of representation. Sanmao is aware of her physical strangeness, but does not allow her identity to overwhelm her presence. Rarely does she interrogate her alien status—peripateticism having long overwhelmed such didactics—and she neither accuses her femininity or ethnicity, nor attempts to defuse them by way of social negotiation. Such qualities are, to her, as transferrable and amenable as clothing. The sharp impressions of her locality has given her life the sense of experiment, and with that thrill of discovery, there’s no time—or need—for self-categorisation. Instead, defamiliarisation leads to an ecstatic shattering of past lives, and she emerges, proudly, in her otherness. In watching, she never wonders what it is like to be watched in return. She refers to her desert home as a Chinese restaurant, exclaims to José that he is “Double-Oh-Seven and I’m the evil Oriental woman in the movie,” and thinks little else of it. It is, perhaps, a definition of freedom.

Still, Sanmao is an outsider, and the perspective of an outsider comes with its own aptitudes. In witnessing a Sahrawi bath by the sea, which apparently involves a rather extensive, seven-day-long series of enemas, the writing slips into gleeful exposé: “We were scared shitless, watching from behind the rocks.” The entrenched methodology of discovering the world by conquering is at the foundation of our conceptualisation of space; because we cannot be physically present without taking possession, our capacity for envisaging mutual terrains is incapacitated. As flippant and obtrusive as Sanmao sometimes is, her redemption is in her unwillingness to subdue. Confronted with the breathlessness of desert wind and its enwrapped people, she is most honest in her enchantments:

There is no other place in the world like the Sahara. This land demonstrates its majesty and tenderness only to those who love it. And that love is quietly reciprocated in the eternity of its land and sky, a serene promise and assurance, a wish for your future generations to be born in its embrace.

In his poem, “Companions in the Garden,” René Char writes: “Let us not permit anyone to take away the part of nature we hold in ourselves. Let us not lose a stamen of it, let us not surrender a sand-grain of it.” Yet arbitrarily, most of us will go on to banish our wildness, displacing it with the grace of functionality and comfort. We are engrained with a binary opposition between humanity and wildness, so what has led to this desire for wandering—the desire for deconstruction? Isn’t there something inhuman, something distinctly pitiful, about someone who refuses to. . . settle down? Ancient Chinese nomads set off on their journeys in search of something—harmony, transcendence—yet Sanmao describes her infatuation not as pursuit, but as homecoming. “A lifetime’s homesickness, and now I’ve returned to this land.”

There are, however, moments when even she is doubtful of her tendencies, especially when the desert reclaims her human comforts:

. . . there is no such thing as excessive joy, yet nor is there much sorrow. This unchanging life is like the warp and weft of a loom, days and years being woven out line by line in an ever-monotonous pattern.

But they are brief and, it seems, too uninteresting to pursue. There is something else wonderful in the distance. Sanmao was born in Chongqing, grew in Taiwan, and became in a myriad of places: Spain, Central America, Germany, the unfathomable Sahara. It seems to me that she adopted the name of a nomad to conquer the presumption that one is forced into migration. Sanmao, the orphaned boy, was the defeated product of a painfully fragmented world. Sanmao, the everywhere woman, is a revelation that dislocation can mean a multiplicity of existences—that stagnancy defies what we owe to ourselves. She surmises that if we are open, the part of nature we contain will lure us back to its boundless motion. Like homecoming.

A passage in the Daoist classic Zhuangzi 莊子 speaks of restlessness: a bird, whose wingspan stretches to impossible extensions, looks down at the sky, so infinitely blue, and wonders if finality even exists. Wildness is the rejection of limits, which is, of course, the rejection of endings.

The legacy of Sanmao in Chinese-language literature is inseparable from her era; her prose did not seek to define or argue in a time when the text had already been perfected as weapon, when the Chinese language was shredded from decades of manipulation and coercion. There is nothing in it resembling deception—not even beauty. Her writing is not beautiful. It seems dismissive of poetry even as she quotes from the classics, preferring to engage with her senses in tactic and haptic lines, a rollicking past tense eliciting the image of someone having rushed home to tell you about some wonderful sight. When she finishes her exhilarated account, she falls back. You have to see it for yourself, she seems to say.

So what does she offer the English-language reader, whose repositories are well-stocked with stories of travel and adventure and awakenings? The screenwriter Shi Hang 史航 said something wonderful: “Sanmao is a girl with cold hands; when she touches warmth, she feels it with more intensity than the average person.” Others have been more brusque: “Strange person, strange behaviours, true love, true words.”

The most powerful story of the volume appears near the end, under the title “Crying Camels,” stemming from the brutal conflict between Spain and Morocco for control of the Western Sahara. It is also one omitted in certain Chinese-language editions. In a rare literary flourish, the story is told in traumatic flashback, culminating in a horrifying public rape and murder. In the Chinese version, Sanmao’s normally short paragraphs are suddenly overtaken by a jarring block of text as she recalls this horror, almost as if she is trying to get the words out as quickly as possible, as if she cannot bear them. The sentences stutter.

The crowd started screaming and fleeing the scene. I desperately tried to get closer, but I got pushed and staggered backwards. I opened my eyes wide, looking at Luat surrounded on all sides. He was pulling Shahida along the ground, his eyes wild and alert, a ferocious glint in them.

As a writer, she tells stories as if she were still trapped inside them, and inscribes her memories as if she needs to be convinced of their reality. She tells her sister—one imagines, dismissively—“One lifetime of mine is worth ten of yours.”

She committed suicide in 1991 at a hospital in Taiwan, over ten years after her José’s death and the end of her nomadism. Three days later, the China Times prints a piece of hers, characteristically plainspoken. For the many women who had grown alongside her, envied her, fallen into foolish, adulating love with her, booked one-way tickets to the Sahara in search of her mysticism—it was the familiar voice of a friend who has returned from a long journey, sitting close on a makeshift wooden chair, one leg up on the seat, hair downed with sand-waves.

假如还有来生,我愿意再做一次女人,做一个完全不同的人,我要养一大群小孩,和他们做朋友,好好爱他们。

我的这一生,丰富、鲜明、坎坷,也幸福,我很满意。

过去,我愿意同样的生命再次重演。

现在,我不要了。我有信心,来生的另种生命也不会差到哪里去。

If there’s an afterlife, I would like to be a woman again, a completely different woman. I want to raise a big flock of kids, to be their friend, to love them well.

This life of mine—rich, clear, rough—has been blessed. I’m full of joy.

In the past, I would have wished to repeat the same life.

Now, I no longer do. I have faith that another kind of life wouldn’t be so bad.

In Chinese, the most common word for dying is “去世,” to leave this world. In Taiwan, they use the Buddhist term, “往生,” towards another life. It is both odd and incredibly painful, and almost miraculous that Sanmao, even in death, urges towards the various. How easily it could have been otherwise—one says in fear, and one says in wonder.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet born in China and living in Tokyo, Japan. shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: