Every year, the prestigious Booker International Prize is always announced to a crowd of critics, writers, and readers around the world with much aplomb, resulting in great celebration, some dissatisfaction, and occasional puzzlement. Here at Asymptote, we’re presenting a take by our in-house Booker-specialist Barbara Halla, who tackles the longlist with the expert curiosity and knowledge of a reader with voracious taste, in place of the usual blurbs and bylines, and additionally questioning what the Booker International means. If you too are perusing the longlist in hunt for your next read, let this be your (atypical) guide.

I tend to dread reading the Booker wrap-ups that sprout immediately after the longlist has been announced. The thing is, most critics and bloggers have not read the majority of the list, which means that the articles are at best summaries of pre-existing blurbs or reviews. Plus, this is my third year covering the Booker International, and I was equally apprehensive about finding a new way to spin the following main acts that now compose the usual post-Booker script: 1) the list is very Eurocentric (which says more about the state of the publishing world than the judges’ tastes); 2) someone, usually The Guardian, will mention that the longlist is dominated by female writers, although the split is around seven to six, which reminds me of that untraceable paper arguing that when a particular setting achieves nominal equality, that is often seen as supremacy; and 3) indie presses are killing it, which they absolutely are because since 2016, they have deservedly taken over the Booker, from longlist to winner.

I don’t mean to trivialize the concerns listed above, especially in regards to the list’s Eurocentrism. Truth is, we talk a lot about the unbearable whiteness of the publishing world, but in writings that discuss the Booker, at least, we rarely dig deeper than issues of linguistic homogeneity and the dominance of literatures from certain regions. For instance: yes, three of the four winners of the International have been women, including all four translators, but how many of them have been translators of color? To my understanding, that number is exactly zero. How many translators of color have even been longlisted? The Booker does not publish the list of titles submitted for consideration, but if it did, I am sure we would notice the same predominance of white voices and white translators. I know it is easier said than done, considering how hard it is to sell translated fiction to the public in the first place, but if we actually want to tilt the axis away from the western literary canon, the most important thing we can do is support and highlight the work of translators of color who most likely have a deeper understanding of the literatures that so far continue to elude not just prizes, but the market in its entirety.

Interestingly, Tilted Axis Press, a small indie press that tends to publish mostly writing by women of color, has not been longlisted a single time by the Booker, although this year it had many strong contenders, including The Yogini by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha and Every Fire You Tend by Sema Kaygusuz, translated by Nicholas Glastonbury.

But if you are here reading this, chances are that you already know all of this. You were probably right there with me on Thursday morning, refreshing Twitter like you had money riding on the results. So, I am not going to reiterate the obvious. What follows will be a very subjective take on this year’s International Booker longlist, with little pretense to any sort of informed objectivity, as I have only read two of the titles.

Honestly, the first sentiment I experienced when I looked at the longlist was a rush of relief; one of my least favorite 2019 books had thankfully missed its chance. Sometimes I feel that I am being a bit unfair to Crossing, written by the young Finish writer Pajtim Statovci and translated by David Hackston. Many readers have enjoyed this book, but I had a really hard time getting past its shallow and often stereotypical depiction of Albania. And if my criticism in the past has focused on its portrayal of my native country, I do think it extends to other aspects as well. Its main character is a shapeshifting, much more tragic Orlando-like figure, but I feel that Statovci has nothing new or original to say about the trappings of identity, and the bruising fight between the forces that define us both internally and externally.

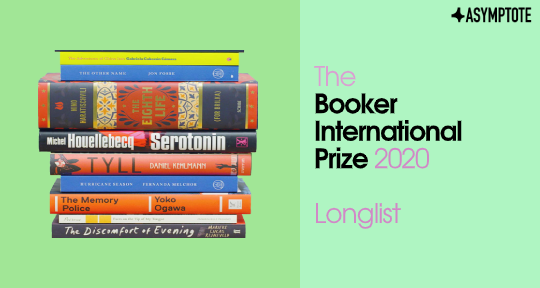

Statovci’s absence on the longlist is not the only choice I feel enthused about. I have already spilled enough digital ink praising The Eighth Life, so I will try to keep this brief. For those of you who are terrified by the book’s length—don’t be. Nino Haratischwili, in Charlotte Collins’s and Ruth Martin’s enchanting translation, has achieved a perfect balance between highly-readable romp and thought-provoking depiction of modern Georgian history. I was also certain that Hurricane Season, written by Fernanda Melchor and translated by Sophie Hughes, would be there. It lingered in my mind long after reading it—not because of the graphic violence that saturates its pages—but from its power in Melchor’s ability to subtly show so much sympathy in even the worst of her main characters. What continues to draw me back to the book are the heartbreaking moments of pity and love, even among the squalidness.

I also expected Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, translated by Stephen Snyder, to be longlisted, though I did worry that her fame might work against her in a prize that has often veered towards uplifting new voices at the expense—so to speak—of more established names. That agenda, however, has not seemed to affected this panel; for instance, this is Samantha Schweblin’s third longlist with Little Eyes, translated by Megan McDowell. The book has been compared to the technological-dystopic drama Black Mirror, although the comparison has not always been positive. I have just started the book, but it’s already incredibly compelling. So far, it’s been mostly set up for the story to come, but the potential for darkness already looms right beneath each interaction, an indication of Schweblin’s fine craft.

The other big name to make the list was Michel Houellebecq for Serotonin, translated by Shaun Whiteside, and this inclusion marked my biggest disappointment with the longlist so far. I am not a fan of Houellebecq’s work; he is supposedly a controversial writer who likes to provoke the more “politically correct” readers by taking his conceits to the extreme, but I don’t find Houellebecq provocative—I find him extremely tiring. Although the segment is no longer available online, journalist Myriam François spoke eloquently to the BBC in October about the place that Houellebecq, Handke, and writers of similar ilk hold in the European literary canon. François argued that the writings Western literary critics applaud and award as provocative are merely a distillation of the same nationalistic ideologies that are the intellectual bedrock of pretty much every European country—they do not challenge the narrative of Europe’s cultural superiority or the status quo, rather they uphold it, often by presenting Muslim people as the “Other” and harkening back to a fictional time, before “multiculturalism,” where Europe was truly at its zenith.

Anyway, beyond these moments of delight, surprise, and frustration, I think the fourth stage was definitely humiliation: I had managed to guess only three of the thirteen longlisted titles and quite a few had completely skipped my radar. And because of this, I’ll bypass the typical plot summaries that can easily be found elsewhere, and tackle the remainder of the longlist as a curious reader.

I have a feeling this year’s panel wanted to give its readers some homework, because a good portion of the longlisted titles can be better appreciated by knowing something of the local context that engendered them. Will Anker’s Red Dog, translated by Michiel Heyns, is an exploration of South Africa’s colonial past through the retelling of a real historical figure, Coenraad de Buys. Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s The Adventures of China Iron (translated by Iona Macintyre and Fiona Mackintosh) focuses on the abandoned wife of Martín Fierro, the protagonist of an epic poem at the cornerstone of Argentinian literature. And Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll, translated by Ross Benjamin, places a staple of German folklore, in the milieu of the Thirty Year’s War.

It’s very difficult every year to avoid reading a certain theme in the judges’ choices; last year, there seemed to be a particular preoccupation with memory, while this year the specter of violence, visceral brutality, and even hauntings loom large. Ghosts seem to feature prominently in Shokoffeh Azar’s The Enlightenment of The Greengage Tree, the only other book from Asia on the longlist, and whose translator has decided to remain anonymous; Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s highly acclaimed Dutch debut The Discomfort of Evening, translated by Michele Hutchison, and even Enrique Vila-Matas’s Mac and His Problem, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Sophie Hughes.

I also need to mention Jon Fosse’s The Other Name: Septology I–II, translated by Damion Sarls. I figured there was going to be at least one Scandinavian title nominated, but someone mentioned Fosse in the same sentence as Knausgaard, and that was enough to strike fear into my heart. Thankfully, I have now been assured that the two are rather different, and that Fosse’s quiet contemplation of rural Norway will be a nice antidote to the brutality that seeps through the rest of the longlist. The periphery is also central to Emanuelle Pagano’s Faces on the Tip of my Tongue, translated by Jennifer Higgins and Sophie Lewis, the other French title on this list, and I believe the only short story collection of the bunch.

I am relieved to have at least read the longest book included in the longlist (the tremendous The Eighth Life), although there are still thousands of pages left to peruse. This will be a busy month (not to mention that Mantel’s final volume in her Cromwell trilogy is being released in early March too!), but I hope to see everyone back here in April for my reaction to the shortlist, which I am sure will be just as baffling.

Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in History from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: