The work of Eduardo Halfon has been translated into English, French, Italian, Dutch, German, and many other languages. However, this year, thanks to the work of educator and translator Raxche’ Rodríguez, his most celebrated short story, and the one from which his entire bibliography sprouts out, El boxeador polaco (The Polish Boxer) has found its way to Maya readers. Entitled Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel, Halfon’s semi-autobiographical story about a grandfather telling his grandson about the origin of the fading tattoo on his arm was published in August by Editorial Maya’ Wuj.

The result is a tiny yet gorgeous pocket version, which includes Eduardo’s original story in Spanish and Raxche’’s translation into Kaqchikel—one of the twenty-two Mayan languages recognized as official languages. With a limited run of five hundred copies, Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel is a little gem that’s now part of the impressive body of work of Eduardo Halfon, recently shortlisted for the prestigious Neustadt Prize.

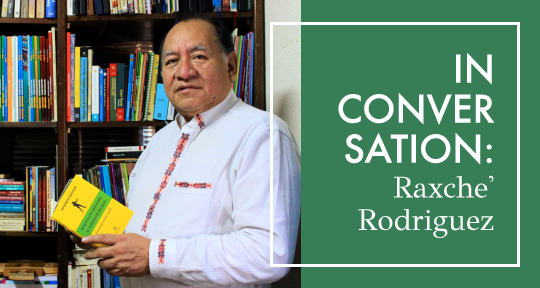

I got together with Raxche’ in late November. He said he was in a hurry—his bookstore and printing and publishing house Maya’ Wuj was working double-time to finish the books commissioned for 2020’s first trimester. But after realizing the grinding of all the machines inside would keep us from hearing each other, he suggested doing the interview somewhere else.

We went out, walked past a mortuary, a park, a couple of bakeries, the national conservatoire, and found our way inside a gloomy restaurant playing jazz.

“Just so you know, I thought it’d be easy,” Raxche’ said, holding his head. “The translation; I thought it’d be easy. It was everything but,” he said, and he chuckled.

“How did this book come to be?” I said, as a waitress, as swift as a bird, laid two glasses of rosa de Jamaica on our table.

“FILGUA,” Raxche’ said. “FILGUA and Humberto Ak’abal.”

This year Eduardo Halfon was asked to write a speech for the Feria Internacional del Libro de Guatemala (FILGUA). In it, he paid homage to the K’iche’ Maya poet, Humberto Ak’abal, and addressed Guatemala’s plurilingualism—2019 was the International Year of Indigenous Languages. Before the event, Raxche’ translated the text into Maya Kaqchikel. But the reading came with a twist. While Raxche’ read Eduardo’s speech in Spanish, Eduardo read it in Kaqchikel. So, the two appeared side by side, on stage, reading in each other’s languages. Philippe Hunziker, the general manager of Guatemala’s most beloved bookstore, SOPHOS, introduced the author with the translator.

“I sent Eduardo a video with an example of the nine additional sounds we use in Kaqchikel,” Raxche’ said. “He spent days learning his speech, and whenever he had doubts, I would send him a voice note.”

Days after the reading, Eduardo texted Raxche’ with the idea of translating El boxeador polaco.

“I thought it was a great idea,” Raxche’ said, smiling. “That afternoon Eduardo announced it on social media. It became official.” But since Eduardo was weeks away from leaving Guatemala, the book had to be made quickly. “As I said, I thought it would be easy.”

Raxche’ began by reading the story several times. He admits he was nervous at first.

Raxche’ has spent the better part of his life working to help protect and promote Mayan languages in Guatemala. Born in Tecpán, Chimaltenango, he has been part of Guatemala’s Academy of Mayan Languages, has translated countless texts from Spanish into Kaqchikel, and is also fluent in K’iche’. In the mid-nineties, as the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996) came to an end, and as indigenous people in Guatemala were finally allowed to group and organize, he, alongside other linguists, helped create thirty-five hundred new words for Kaqchikel speakers. To do this, they first considered whether any words that were no longer in use would help them explain these new terms. If none worked, they checked if other Mayan languages already had a word available. If they couldn’t find any, they made up new words. One fine and beautiful example is “kematz’ib,” which means “computer.” Raxche’ and the other linguists arrived at this new word by combining “kem”—“weaving,” “a”—“connects to roots,” and “tz’ib’”—“writing.” A computer is, after all, a machine used, partly, to weave written words. This glossary was later taken to the communities. After that Raxche’ has continued his work writing, translating, printing, and taking educational texts to small communities across the country. Surprisingly, El boxeador polaco was his first literary project.

“So, don’t act surprised when I tell you I was nervous,” he said laughing; his laughter, and all the sounds inside the restaurant, suddenly grew dim as horns and sirens exploded in the street.

First, he said, came the title, which was not a straightforward translation.

Polonia (Poland) doesn’t exist in Kaqchikel so Raxche’ used an approximation based on the location of Kaqchikel speakers. Next to Tecpán, his hometown, there’s another village called Santa Apolonia, so he used the grammatical likeness to create Polo’n. Every demonym in Kaqchikel comes with the prefix Aj. So Polaco (Polish) became Aj Polo’n. He chose not to keep Polonia or Apolonia, in part, because in Kaqchikel, words rarely end in a vowel. And Ch’ayonel, well, Kaqchikels don’t have boxeadores (boxers), or a sport based on punching either. They do have, however, a word they often use to refer to someone who hits someone else, Ch’ayonel. And so, El boxeador polaco or The Polish Boxer became Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel.

“As soon as Eduardo heard it, he loved the title,” Raxche’ said. “But, as you can imagine, there were a lot more terms, words, or entire phrases that weren’t available in my language.”

Halfon mentioned in his story a Bayer pill, which Raxche’ translated, literally, as a round medicine with Bayer printed on it. “We as a culture have not produced pills; we have pastes, teas, drinks, or other medicines, but not pills,” Raxche’ said. Halfon wrote in his story, in Spanish, that his grandfather asked for another finger of whiskey, Écheme un dedo más; which Raxche’ translated as a big drop of whiskey. Raxche’ was forced to improvise and innovate. But perhaps the most exciting linguistic element that Raxche’ used to complete the translation was the use of the pareto, which he explains is a type of repetition Mayan speakers use to intensify the feeling.

“We would say things like, ‘We went up, went down, climbed mountains, and crossed valleys to come to your house,’” Raxche’ said. “This is how ceremonious our language and culture is; this repetition and lengthy explanation is the pareto.”

Paretos, Raxche’ said, are often used in poetry.

“For other languages, this might be too repetitive, but this is part of our culture, and it doesn’t sound bad,” Raxche’ said. “‘I’m sorry, excuse me, that I kept you waiting, that my delay has been the cause of your exasperation, but now I’m here, and we can talk, we can have a conversation,’ that’s pretty common in Kaqchikel. I used similar paretos when translating Eduardo’s story to try and replicate his rhythm.”

Halfon has said repeatedly that his editing process is based on adding rhythm and musicality to his stories. Repetitions as well.

One can easily see this at the end of his 2017 novel Mourning, when a character named Doña Ermelinda lists all the children that had drowned in Lake Amatitlán.

“She told me that the drowned boy was not named Salomón, but Juan Pablo Herrera Irigoyen . . .”

“She told me that another drowned boy was also not named Salomón, but Luis Pedro Rodríguez Bat.”

“She told me that another drowned boy was also not named Salomón and was also not a boy, but a girl named María José Pérez Huité.”

“I realized pretty early on that he had linguistic and literary elements that I didn’t have access to,” Raxche’ said. “So, I had to make good use of the elements that make Mayan languages unique, elements like the pareto. And even if I needed two, three or more words to say what Eduardo had said, I knew this would add a memorable musicality to the story, much like the original.”

Unsurprisingly, there was one element of Eduardo’s story which Raxche’ knew too well: genocide.

In El boxeador polaco, we see a grandfather telling his grandson (also named Eduardo) for the first time, the truth behind the five numbers tattooed on his arm. “69752. That it was his phone number. That it was tattooed there, on his left forearm, so he wouldn’t forget it,” Eduardo writes. The reality is, of course, much grimmer. Eduardo’s grandfather, both in the story and in real life, was in Auschwitz during the Holocaust. In the Second World War (1939-1945) Nazi Germany systematically murdered six million Jews, including many of Eduardo’s relatives. In 2013 a Guatemalan court determined that during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996), the Guatemalan army committed acts of genocide. Its main target: indigenous Mayas.

“Eduardo’s people and my people, Jews and Mayas, have been historically persecuted. Both have been the victims of genocide,” Raxche’ said.

Nima kamik. They are the words Kaqchikels use to describe genocide, and it means a large provocation of death. The use of Nima kamik dates back to the Rabinal Achí, a Maya play written in the 1600s in K’iche’. It was all too familiar. And it goes beyond the genocide too. While Jews, during the Holocaust, were placed and starved in concentration camps, Mayas, during the Guatemalan Civil War, were put in similar confinement in what were called aldeas modelo. In these aldeas the Guatemalan Army surrounded indigenous peasants with the promise of food, shelter, and employment; they did so to keep an eye on them so they wouldn’t be able to help the guerillas. But in reality, soon aldeas modelos became a place of sickness, starvation, and death. The Mayas, much like the Jews, were persecuted, massacred, tortured, and forced to find asylum somewhere else.

“After spending a life living this persecution, it wasn’t that hard to get all the nuances of Eduardo’s story,” Raxche’ said.

Raxche’ finished translating El boxeador polaco two weeks before the presentation. Then, Maya’ Wuj’s editors read the manuscript and made sure that Raxche’’s choice of words was consistent with standard Kaqchikel. For example, for Raxche’, and for all Kaqchikel speakers in Tecpán, “me” is “Yin,” while the standard Kaqchikel is “Rin.”

Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel hit the shelves on August 13, 2019.

“I don’t see a translation of literature as a treason—as Umberto Eco famously said: traduttore, traditore—but rather as a new contribution,” Eduardo Halfon wrote to me, from his residence in Paris. “Every time one of my books or stories gets translated, that translation also affects the original. Sometimes, for instance, a translator quite simply finds mistakes or typos. But other times the translator finds a solution to a specific linguistic or even structural problem. For me, a story is very much alive. In this specific case, however, a translation into one of Guatemala’s other many languages is also a political statement.”

Librería Maya’ Wuj sits on the edge of Guatemala City’s Zone 1. Inside there are dozens of shelves with hundreds of books. Inside, you can find many dictionaries, children’s books, and textbooks, all bilingual. There are some books only in Spanish, naturally, but most are in one or more Mayan languages. Maya’ Wuj has also put out many books of the famed K’iche’ poet Humberto Ak’abal, and you can find an extensive collection of his poetry there. The shelves are also filled with Maya history, historical texts, anthropological research, historical findings, testimonies of those who survived the genocide, books written by former guerillas, etc. But there are also earrings, necklaces, and wristbands with a Nawal printed on them. Nawales, according to the Maya, are the energies that bind the universe. Every person has a Nawal based on one’s birthday. I myself am B’atz. The monkey. The thread of time. After the interview, Raxche’ was kind enough to give me a calendar, a cholb’al samaj, which was made combining the Gregorian and the Maya calendar. And, amid that immensely diverse bookstore, there is Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel, shining its tiny head with subtlety, elegance, and potency.

“This book represents a triumph for Maya readers,” Raxche’ said, holding a copy in his hands; the machines have not stopped cutting and grinding and pushing since we left. “But there’s still a lot of work to be done.”

When I asked Raxche’ what kind of response the book has gotten, he said it has been mixed. Even if people, many people, applauded the translation—for its faithfulness, inventiveness, and inclusivity. Even if people who had not read the story before liked it. And even if Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel has now become a collector’s item to all Halfoners, he said Maya readers rarely have a chance to read books in translation. Or to put it in a different way, books rarely, seldomly get translated into Mayan languages.

“We don’t have access to many books because we don’t have enough readers,” he said. “Or perhaps we don’t have readers because we don’t have access to many books.”

Yet Raxche’ is hopeful.

“This is only the beginning,” he said. “In 2003, when we pushed for a law to help protect and promote Mayan languages in Guatemala, people thought we were crazy and wrote op-eds saying that that was a step backward for the country, un retroceso. Yet, in 2010 Windows released its operating system in K’iche’.” As if bitten by an unexpected phone call, Raxche’ reaches for his cellphone. He shows it to me after a few clicks and swipes. “What language do you see?” he said, holding the screen under my chin.

“¿Español?”

“Now look,” he said, touching the screen. Raxche’s WhatsApp suddenly blinks from Español to K’iche’. “Every Android device can be used in K’iche’,” he said, proudly. “We have proven, time and time again, that our culture is very much alive and well. And we will continue to do so. To protect and promote indigenous languages is not a retroceso for Guatemala, or any country; it’s a way to acknowledge the multiculturalism of this land and the history of our people.”

After Ri Aj Polo’n Ch’ayonel came out, Eduardo suggested that Raxche’ keep translating his stories into Mayan languages.

“I told him we should publish my stories one at a time,” Eduardo said. “Perhaps one every couple of years, but that each story could be in a different Mayan language. If The Polish Boxer is in Kaqchikel, maybe Distant could be in K’ekchi’, or even Signor Hoffman in Mam. Why not?”

El boxeador polaco has been translated into twelve languages: English, French, German, Italian, Dutch, Portuguese, Croatian, Norwegian, Macedonian, Japanese, Israeli, and Kaqchikel.

Raxche’ Rodríguez (1957) is an educator, editor, translator, coordinator of several linguistic projects made to advance Mayan languages, and editorial director of Maya’ Wuj. He’s Maya Kaqchikel and speaks Spanish and Kaqchikel. He’s the author of several books and investigations based around education, bilingual education, and Maya culture and history.

Eduardo Halfon was born in Guatemala City, moved to the United States at the age of ten, went to school in South Florida, studied industrial engineering at North Carolina State University, and then returned to Guatemala to teach literature for eight years at Universidad Francisco Marroquín. Named one of the best young Latin American writers by the Hay Festival of Bogotá in 2007, he is also the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Roger Caillois Prize, and José María de Pereda Prize for the Short Novel. He is the author of fourteen books published in Spanish and three novels published in English: The Polish Boxer, a New York Times Editors’ Choice selection and finalist for the International Latino Book Award; Monastery, longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award; and Mourning. Halfon currently lives in France and frequently travels to Guatemala.

José García Escobar is a journalist, fiction writer, translator, and former Fulbright scholar from Guatemala. His writing has appeared in The Evergreen Review, Guernica, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. He is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for the Central American region. He works as a journalist in Agencia Ocote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: