Despite a good deal of justifiable hysteria concerning the survival of print literature in the age of online publishing, new media, and a ruthless attention economy, it seems that the words of Umberto Eco have proven to be withstanding: the book will never die. The text has only become more malleable and diverse as new platforms are granted to it; literature’s performance is the same as that of a drop of paint in a glass of water—the entirety is invariably adopted into its presence. As devotees of the book, however, we at Asymptote found ourselves engaged by the artform that seems to lend itself particularly to the cooperation with literature: film. So, we present the debut of Asymptote at the Movies, in which we discuss cinematic adaptations of our favourite translated works and authors from the lens of readers, to discern and investigate that other enigmatic process of translation, that from the text to the screen.

Our first film is Paul Schrader’s masterful Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, an uncompromising and transcendent film that ideates scenes from the Japanese author’s life in juxtaposition to three of his novels: The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House, and Runaway Horses. Below, the blog editors talk about Yukio Mishima’s authorial presence in cinema, the literality of images, and the sensuality and emotionality of film’s structural elements.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): In a 1966 interview, Yukio Mishima quotes the pivotal line from Hagakure, the spiritual guide for samurai: “The way of the samurai is found in death.” He committed suicide four years later, after a lifetime under its fantastic thrall, leaving behind a legacy of language that dreamed in equal ecstasy of death; as a longtime reader of his work, I’m convinced that he intended his existence to be triumphantly underscored by this violent and dramatic end, and Paul Schrader evidently feels the same way. Of the many axioms that Mishima lived and wrote—beauty, purity, honour, truth—Schrader situates the author’s inveterate obsession with death as the ancestor of his work and life, and the suicide as the culmination of a lifetime of justification. So it is that he combines scenes from three of Mishima’s novels that delves most deeply into the psychology of devoted self-obliteration. I’d like to start by talking broadly about this film’s narrative, and as to what you both thought of the director’s Pirandellian choice, to render the author indistinguishable from his characters within such a fluid account, in which the fiction bleeds seamlessly into vérité.

Rachel Allen (RA): “Pirandellian” is interesting: I think of Mishima (Schrader’s Mishima, but maybe also Mishima’s Mishima) as inveterately authorial, with action (and sometimes also actors) as what must be sought. He’s so emphatic about distinguishing word from world. His body is the secondary thing, realizable only by previously established creative faculties. He insists, in voiceover, on the primacy of narrative identity, and the effect of the movie is to grant it him, as his verbalizations manifest visually. The seppuku “story” anchors the film’s relationship to chronological time, but most of the actual screen time goes to “discourse”—narration that begets recollection, re-imagination, and recreation of Mishima’s (ever-inter-animating) life and works, what seemed to me like cinematic-Mishima’s mental contents on his last day on earth. It reminded me of the Quentin Compson section of The Sound and the Fury, thematically, but the literalness of photography allows/demands substantiation, which is where Schrader is able to utilize Mishima’s real-making powers as the author of his activities.

The first time I saw Mishima, I thought it Schrader cast it like Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, and that all of these actors were straightforwardly (or “straightforwardly,” I guess) playing Mishima, the way Carole Bouquet and Angela Molina are both playing Conchita. And now . . . I’m not sure that that was so misguided. Is there a sense in which actors are not all playing Mishima? Could this film have been cut as “randomly,” as Buñuel’s ostensibly was, each of them appearing as an interchangeable part of a single Mishima whole?

Sarah Moore (SM): Thanks for starting the discussion, Xiao Yue, and for your response, Rachel. I think the film always had to be Pirendellian in order to portray an author whose own life and creative work were so closely linked. Your emphasis on “action (and sometimes also actors)” is interesting, Rachel, as both Schrader and Mishima are concerned with how much one’s identity is determined and how much it can be shaped and remade into a new, equally valid one. Some key scenes stand out for me—firstly, when Mishima is taken as a child by his grandmother to the theatre. Having been repeatedly told that he “is a delicate flower,” here he catches sight of an Onnagata actor in the dressing room. The idea of “delicacy” and of playing out a predetermined role is suddenly destructed. We see it again with the stuttering young man in the “Beauty” chapter (dramatizing The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) who learns from his friend that this supposed defect can be used to his advantage, through acting, to attract women. This performative aspect of Mishima is crucial. So, yes, I think there is a sense in which actors are all playing Mishima, but are playing a potential version of Mishima. But I don’t think the film could have been cut “randomly”—I think its structure is deliberate and necessary (not least in its separation into four chapters.)

Despite the interweaving of the three time sequences, they do proceed to show a development in Mishima’s thought and the construction of his artistic philosophy. What did you both think of the film’s structure? And the decision to separate it into four chapters?

XYS: I agree with you, Sarah, in that there is a very conspicuous crescendo in the structure, but I felt that the various cinematic Mishima-proxies (rendered, I felt, somewhat forcefully from their textual counterparts) are not interchangeable or hypothetical, but instead unidimensional motifs of original-Mishima’s doctrines. To specify, I don’t take the uni-dimensionality as so much a flaw as a formal necessity, but it reinforces this film’s tendentious definition of Mishima’s life, and the intersection between fictions and realities is constructed in service of the film’s exigency for intertextual corroboration. The idea of it having granted to Mishima the “primacy of narrative identity,” as you say, Rachel, is perhaps understated by such depictions of characters as qualities. Suicide and its commandants: insecurity, arrogance, nihilism.

To reiterate, the artistry of the film is dependent on this intentional repurposing of the literature to serve a psychoanalysis.

As for the separation into four chapters, I would guess that it’s a reference to The Sea of Fertility tetralogy (though only Runaway Horses features in the film), though structurally it acts less like an infrastructure and more like an info-structure. All of the recognized “plot points” are driven by emotion, not narrative, and as Rachel mentioned, much of the language is language of the interior, not of communication. In reference to Tony Bennett’s exhibitionary complex, museums have instilled into the public a method of sequentialized looking, and it is in both the acknowledgment and inversion of this concept that I am most awed by Schrader—there is no hegemony in this film.

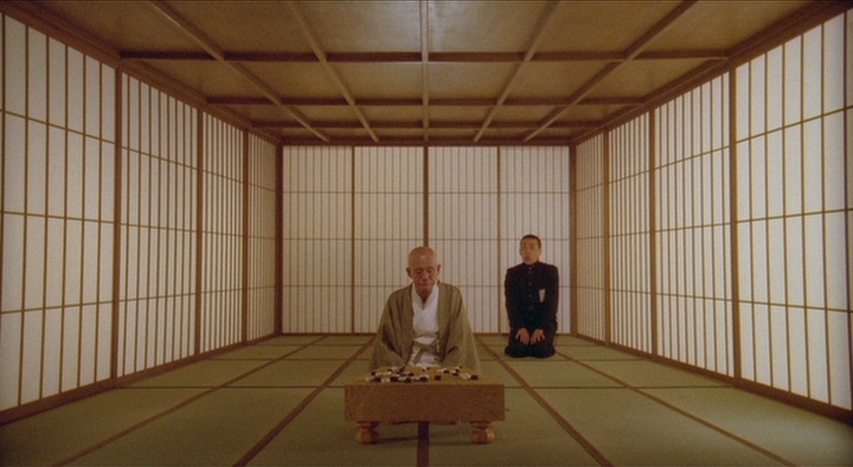

RA: Your mention of museums, Xiao Yue, recalls for me Eiko Ishioka’s use of partitions to create these dioramic sets, the establishing shots of which are often from above. (I kept having the thought of stages cordoned off from voids.) Design, here, does not seem to have its usual function of representing interior states. Schrader grants it the status of a fundamental conceptual unit, a basic structural element of Mishima’s emotional life and thus of the film. This may be what you’re getting at, Sarah, with regards to deliberateness, and Xiao Yue, to emotion: even though Mishima lacks certain traditional narrative engines (clear patterns of material causation, say), it still seems like a coherently-sequenced work. I think I would agree with you, Xiao Yue, about its logic and structure being primarily emotional-intuitive; I would also posit that, far more than in most narrative (literary or cinematic) works, design constitutes structure in Mishima. The way things seem, sensuously, is not just inseparable from the way they are, but also from what is happening; I don’t know that there could be “plot” apart from staging. (Mishima’s coup is unimaginable without the uniforms.)

Mirrors were interesting to me in this movie: they’re prevalent. Most memorably, they show up when (not-)Mishima literary analogues are in bed with female lovers. In the brothel, there’s an oddly placed single pane mirror in a corner overhead; then, in that fabulously pink-lit hotel room, a different lover (of a different Mishima) holds her compact between them:

Mishima’s well-established fascination with masks has, by this point in the film, been acknowledged as part of the overall sartorial strategy; we’ve seen child-Mishima marvelling at the way mask and costume turn (male) actors in the theatre into beautiful women. The camera lingers in the gauzy hotel light as (not-)Mishima’s lover’s hand drifts downward, and holds the moment when she’s between their two breasts with the two almost merging, so that her breast is (in the mirror, through the camera) his breast. I wondered about that as an inversion (or an inversion, inverted, since the camera too would’ve employed a mirror) of prior theatrical representation, also strongly gendered. I was thinking of mirrors as (rare) points of both convergence and refraction within the movie, since Schrader is mostly inclined to operate on Mishima’s prescribed plane. A mirror affirms and distorts; in either case, it assumes (or supplies) a surface/appearance in addition to (not coextensive with) reality. That seems to be the case also with masks. I wonder if you masks and mirrors might have dual or complementary roles in Mishima?

SM: I agree, Rachel—mirrors absolutely stood out for me in this film (and especially that scene you mention where Mishima’s lover holds her compact mirror over his face). And I think mirrors and masks certainly do have complementary roles in this film with regards to beauty, aesthetics, and sexuality. In once scene, before he has begun bodybuilding in his quest for physical perfection, Mishima watches a group of men dancing and the voiceover narration says (in a passage adapted from Confessions of a Mask): “I also wear a mask. I also play a role. When he looks in the mirror, the homosexual, like the actor, sees what he fears most: the decay of the body.” Later, after his dance partner has offended him by suggesting his body is turning flabby, Mishima explains his anger to him: “Both you and I have a strong sense of aesthetics. When you look in the mirror, you see beauty. I can’t even look at myself.” The mirror is always a potential threat, capable of revealing a body beyond its peak of perfection, beginning to decay. It is often equated with the gaze of another, in front of which one is revealed as inadequate. Therefore, I think the mask is complementary in that it can serve as a distortion and a diversion from the reality of the mirror. I think both are related temporally as well: to Mishima’s search for the “moment” rather than eternity—or rather, realising eternity in a moment (“I wanted to explode like a rocket, light the sky for an instant, and disappear.”). Mizugochi says of his speech impediment: “It’s like a mirror you can’t break.” The mirror is constant, whereas the mask can be momentary. And this is certainly also related to Mishima’s seppuku, decided partly by the idea of committing suicide “at the height of your beauty.”

Xiao Yue, you’re right that the film is driven by emotion rather than narrative. Yet the action is accompanied by the extremely sparse voice-over narration. The incredibly vibrant visuals certainly take precedence in the film (as well as the phenomenal score by Philip Glass!) What do you both make of the voice-over narration within the film (and the score!)?

XYS: I’m so glad that Rachel brings up the sets—such beauty, such imagination, such phantasmal structures of narrative and experience! They provide a utterly unique haptic continuum that instills Mishima’s realist fictions with an incredibly special and corporeal, yet permeable geometry. Ishioka had said that she intended the sets to be “actors, and they would challenge the real actors.” I think of her, and her intentions of compounding the emotional engagement between person and place, as perhaps the most significant attribution to the artistry of this film. Cinema, as it involves a configuration of fixed optics, has the somewhat illogical job of situating a dynamism within the static spectator, introducing a new spatiovisuality. This film accomplishes that by introducing spaces that are equally as choreographed as the actors, making it so that we are given the appearances of travelling through them, but creating a link between body and environment that encourages us to make tangible our pre-existing knowledge of exterior as an extension of the interior, excluding the typical infrastructure of a subjective looking into the objective and obviating, as Rachel mentioned, the mediation of representation. I found it such an exquisite cinematic iteration of what Lefebvre defined as social space, one in which “social phenomena, including products of the imagination such as projects and projections, symbols and utopias“ occur, conspicuously separate from mental space, which is occupied by “formal abstractions about space.” That one scene in which Kinkaku-ji splits down the middle and opens up, revealing that it’s impenetrability and flooding the screen with gold . . . I remember gasping. Space, inoculated with lived experiences and penetrated with our motion, is indelibly alive. Mishima’s fatalist, erotic, ritualistic obsession with beauty is installed into this scene with such visceral transversality.

And yes, with mirrors, especially in that scene with the compact, I was reminded of the folklore that mirrors steal your soul. In accordance with fengshui, mirrors should never face the bed, as one should never be confronted with the somewhat traumatic image of oneself in the weakened state of hypnopompia or hypnogogia. They will also negatively affect the relationship between lovers, by evoking the presence of an intruder within the field of intimacy, so I find that scene in which the two are in bed particularly menacing. The gendered aspect, referential to Mishima’s homosexuality, culminates in that scene, in which our emotional reactions to beauty are really inversions of our ideas of self. That whenever we are with someone, we impose ourselves upon them, enforcing the other into the role of the mirror.

I love that Sarah points out the search for eternity within a moment. it is truth that exists on the same plane as eternity, and mirrors always tell the truth; it is just that truth switches hands, so that whoever possesses the mirror is possessive of truth, and also eternity, and essentially exerts a possession over the object that is obstructed, as opposed to reflected.

As to the voiceover, narration always performs the function of retrospect, in conduct of rational procession and individual liberation, appropriate to Mishima’s wield of the I-novel. It is to return the command of the narrative back to the subject of it, somewhat obfuscating the role of the writer, and this refers back to what Rachel referred to as Mishima’s “real-making powers as the author of his activities.” Voiceovers also compels a gravitas over the audience; spectators automatically respond to telling, as when we are told something, we are simultaneously aware that it is worth hearing. Score resonates with the same function by manipulation our emotive responses (immaculately in this film, as the music has literally brought me to tears), and therefore negotiates with the peripatetics of film by identifying its functions.

Narration also create a lapse in our temporal knowledge, in the way that cinema always defies time. Literature is more impotent in this regard, as it is always grounded—at least by way of its physicality—in bounded, categorized time. Literary narration, mobilized to cinematic narration, reinforces the origin of cinema as an art of viewing; the authorial voice directs, but is relieved of the role of describing. Yet it is also powerful in that it continues to infuse the film with cogent sincerity, meaning that is synonymous with honesty and truth, and creating a coherent hyphen between beginning and end. Noting that the voiceover is in English, however, is an activation of the transference of language from the dead to the living—Mishima can’t speak, and so it is the spectacles and consequences of his creations that must speak for him. It evokes the profound pronouncement in the last line of The Temple of the Golden Pavilion: “I wanted to live.”

Sarah Moore is a bookseller and editor from Cambridge, UK. She currently lives in Paris and is an Assistant Blog Editor for Asymptote.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor, born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her poetry chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was the 2018 winner of the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize. She currently works with Spittoon Literary Magazine, Tokyo Poetry Journal, and Asymptote. Her website is shellyshan.com.

Rachel Allen is a writer based in New York. Her work has appeared in Best American Experimental Writing 2018, Full Stop, The Fanzine, and Guernica, of which she is an editor. She is also an assistant blog editor at Asymptote and a graduate student in philosophy. In 2019 she was in residence with the Tulsa Artist Fellowship.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: