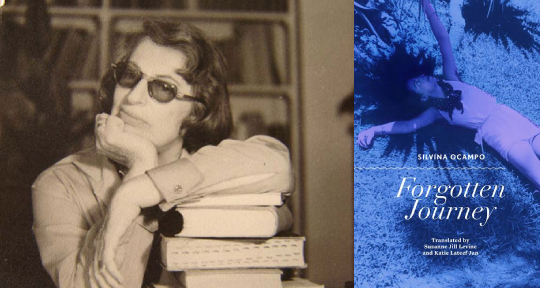

Forgotten Journey by Silvina Ocampo, translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan, City Lights Books, 2019

Silvina Ocampo (1903-93) was once called “the best-kept secret of Argentine letters.” Luckily for Anglophone readers, however, more of her work is being gradually revealed, most recently with two publications by City Lights Books: The Promise and Forgotten Journey. The Promise is a novella which Ocampo spent twenty-five years completing, whilst Forgotten Journey, translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan, is her debut piece of fiction, a collection of twenty-eight short stories originally published in 1937 as Viaje olvidado.

Ocampo may be under-recognized outside of Argentina, but during her lifetime she was part of an elite literary and intellectual circle formed by Jorge Luis Borges. Along with Borges, and her eventual husband Adolfo Bioy Casares, she collaborated on a famous anthology of Fantastic Literature and formed friendships with authors such as Virginia Woolf, Paul Valéry, Lawrence of Arabia, Federico García Lorca, and Gabriela Mistral. She was also a visual artist, having trained in Paris under Fernand Léger and the surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico.

These surrealist influences are evident in her writing, and there is undoubtedly a fairytale quality to Ocampo’s stories: fairytale in the sense of its truest origins—innocence is flooded with the dark and the ominous, childhood confronts and battles adulthood. Throughout Ocampo’s tales, there is always a moment when death enters, knocking the innocent out. And these stories are dark: a horse is whipped to death, a servant murders the young son of her mistress, a woman’s pet is brutally killed by a jealous lover. The duality of dream and nightmare is always present, similar to writers such as Leonora Carrington, Angela Carter, and Clarice Lispector. In a 1982 interview with Noemí Ulla, Ocampo says that Lispector wanted to meet her in Buenos Aires, and Ocampo was devastated not to have done so before Lispector’s death in 1977.

However, to only compare her to these writers is definitely to overlook her own style and invaluable contribution to Argentine literature. Ocampo’s conjured worlds are wondrous, bold, and unique. Common topics for her stories include childhood, young girlhood, an awakening sexuality, the threat of death, shifting identity, fate, and memory. Her stories give voices to historically marginalized characters: servants, women, and children. Settings are often domestic, but portray a domesticity that has been disturbed and where family relationships are strained, unpleasant, cruel, or even lethal.

One of the most interesting facets of her writing—and indeed, one that makes any truly great writer of short stories—is that of perspective. Her narrators’ glances never come from somewhere expected, and always land on something unpredicted. In the very first story in the collection, “Skylight,” our gaze is pulled voyeuristically upwards, to watch firstly the elevator with its “uncoiling elevator cables,” and then up to the glass skylight through which the young narrator observes the family living above. The short story encapsulates a whole family’s world through this tiny opening into their lives’ rhythm. Each person’s character, activities, movements, motives, and emotions are shown to us by their feet and clothes seen from below, or by their voices descending—perhaps this visuality can be attributed to her initial training as a painter. Ocampo is a master of fitting an entire life’s meaning, desire, and regret into a miniscule amount of space, into a fleeting moment. Miniature and giant inflate and shrink before our eyes.

As the academic Patricia N. Klingenberg writes in a study of Ocampo, “the child provides an ideal vantage from which to project the estranged world.” Ocampo does favor child narrators, and from these always-unusual perspectives, it is as if what we thought we knew of the world suddenly contorts into new realities. Reading her short stories has the effect of seeing an enlarged eye behind a held-up magnifying glass: her studied, silent observation reveals the significance of the seemingly mundane. Ocampo is so in tune with nuances of emotion that they come to carry the stories, taking on physical forms themselves. In “The Enmity of Things,” the unnamed protagonist, who has become overwhelmed by the heavy burden of accumulated objects, revisits his childhood home and fondly remembers having taken walks there when “joy would take him by the hand, leading him across the courtyard.” Later in the story, in one of the most remarkable passages in the whole collection, he becomes anxious at the growing distance and unfathomability of his girlfriend:

“What are you thinking about?” To which she replied with an impatient wave of her hand, and that impatience ballooned, spring-loaded, from contact with his gestures, from contact with his words. From then on he could no longer walk without stumbling or swallowing without making a strange noise, and his voice flowed freely in the moments when silence was most needed. The hatred or indifference awakened that day loomed before him, solid and palpable as a stone wall.

Eventually, as their relationship resolves itself, his girlfriend’s voice on the telephone is “tenderness for him alone—a bed to sleep in when exhausted.” Yet Ocampo is never sentimental; the devastating heartbreak of her stories comes from the suddenness of emotion, which is always comprehended too late, through memory. For so many of her characters, the narrative arc of their lives pivots on the memory of a moment at which a loved one, or the opportunity of intimacy, was lost to them. In “Eladio Rada and the Sleeping House,” Eladio lives alone in a large, dusty house and keeps a photograph of a past girlfriend in “a big box full of nails, newspaper clippings, and old pieces of wire.” Although they had only gone out together several times, “it seemed like these were the only memories of his life.”

The title story, “Forgotten Journey,” reveals two of the collection’s major themes: travel and memory. Both concern Ocampo’s preoccupation with identity—especially the fear of losing an identity or the hope of discovering a new one. In “Forgotten Journey,” the unnamed female protagonist tries to remember the day she was born but “could never reach back to the memory of her birth.” The fantastical stories she creates to explain how we are born are eventually mocked and corrected by her sister (“cruelly three years older than she was”) and her mother. “In each memory she was a different little girl but always with the same face,” yet the revelation of the truth induces enormous anxiety and darkness in her: “when her mother said that the sun was lovely, she saw the black sky of night where not a single bird sang.” Similar ideas take on different form in “The Backwater;” two sisters grow up on a ranch together, in seemingly innocent happiness. However, as they grow older and become more and more estranged from themselves, increasingly sadder, and outgrow their clothes, they “take two divergent paths . . . Libia married the first man who offered to take her away to live with him near a paved road” while “That same day Cándida, without any goodbye to her parents, took a train to Buenos Aires, carrying with her a bundle of dresses with the empty sleeves of her friends.” Her female characters often face a choice between remaining or escaping. Clothes also hold enormous significance throughout her writing, as both an immediate marker of identity, like a passport, and as a restraint. Her female narrators seek freedom—both economic and geographical, as well as an internal, spiritual freedom. Throughout Forgotten Journey, people move like light and shadow, pass into the frame, and disappear from view, just as they do in our lives. In “Eladio Rada and the Sleeping House,” the titular character interprets the changing seasons, not by the sky or the temperature, but by the comings and goings of the people around the house. It seems that what Ocampo is really grappling with is the question of how to endure instability and the inevitable transience, impermanence of human life and human relationships.

This translation from the Spanish is a tremendous accomplishment and, interestingly, was a collaboration between Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan. Ocampo is known for her unusual and playful Spanish. When her own sister, Victoria, reviewed Forgotten Journey for the first time in her well-known journal Sur, she criticized Ocampo for using grammatical mistakes. Ocampo used colloquial Spanish, absurd language, and broke the rules of traditional grammar. Levine and Lateef-Jan have very skillfully kept this wit and imagination alive in their translation. A literal translation is often foregone to save the humor or spirit of the original.

English translations of Ocampo are overdue, and I hope that more of her work continues to be made available in English. Italo Calvino said of her: “I don’t know of another writer who better captures the magic inside everyday rituals, the forbidden or hidden face that our mirrors don’t show us.” Like watching the world through a glass prism, Forgotten Journey is wonderfully strange, mesmerizing, and utterly original.

Sarah Moore is a bookseller and editor from Cambridge, UK. She currently lives in Paris and is an Assistant Blog Editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: