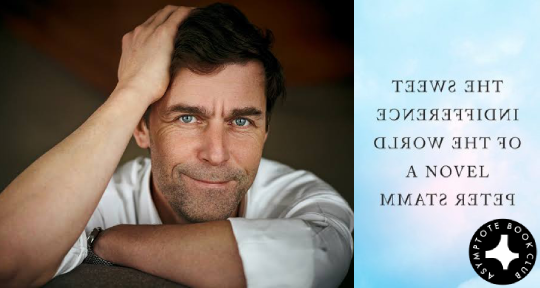

Do writers aspire to live forever? Is literature a cultivated method of extending our capacities, prolonging the temporary, and rectifying our past mistakes? In this month’s Book Club selection, Asymptote has selected lauded German author Peter Stamm’s latest novel, The Sweet Indifference of the World, which probes such questions with a graceful awareness of how human relationships materialize and dissipate. Cohered by a love story told and retold, Stamm deftly enwraps complex psychological themes of identity and memory in his polished prose, translated into English skillfully by poet Michael Hofmann.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

The Sweet Indifference of the World by Peter Stamm, translated from the German by Michael Hofmann, Other Press (US/Can) & Granta (UK), 2020

What casualty of a failed love affair doesn’t leave some phantom of themselves wandering eternally through their memories, in search of what could have gone differently? Peter Stamm’s The Sweet Indifference of the World, translated from the German into understated, efficient English by Michael Hofmann, invites the thrilling possibility of the alternate ending. Christoph, middle-aged and still coasting on the success of his first and only novel, recalls his relationship with actress Magdalena, grasping at a slippery opportunity to finally salve his unsatisfied soul.

The masterful craftsmanship of both author and translator animates a universe that trembles on the limit of realism. An elevation from the typical love story, the novel invites meditation on topics like the nature of narrative, the unreliability of perception, the standards by which we judge the value of a human life, and even the act of translation.

Christoph has aged and has no idea what’s become of his Magdalena when he comes across a young couple, Chris and Lena, their doppelgängers. Christoph invites young Lena on a destinationless walk during which he will recount his love story, which she quickly recognizes, from that most elusive perspective: the other one. In retrospect. The driving question for both becomes whether or not the two stories will follow the same trajectory—and whether the telling itself will impact the answer. Where Christoph is repentant, Lena is accusatory, a tension with an unpredictable resolution: “Did you say that to her? Lena asked me with an urgency that surprised me. Did you try to win her back? I didn’t reply. Lena let go of my arm and stopped. When I turned towards her she looked at me sharply and said, I don’t think he’s anything like you.” The telling of the story revises it, liberating it from teleology.

Mythologically, doppelgängers are often harbingers of bad luck, especially when spoken to; the fact that Christoph provocatively begins stalking them inverts the trope, troubling one of the basic assumptions of the novel. Christoph is presented as the protagonist, and the novel is written almost egotistically from his perspective. He calls Chris his doppelgänger, and Lena Magdalena’s, but what if Christoph, who fancies himself the leading man, is actually the couple’s bad omen, or their savior, or simply a neutral factor in the free decision-making process of two autonomous individuals? The doppelgänger is a shifty figure, akin to a twin or a clone, frustrating Christoph’s conviction that he knows it—or himself. Chris interrogates Christoph about their life:

When I answered correctly, he gave a quick nod, and went on to the next question. If my answer didn’t satisfy him, he shook his head, and said, You see! There are deviations, I said, there are bound to be. It’s not possible, he said . . . So, tell me, what’s the book going to be called that I’m going to write in a few years’ time, the one you say you published a long time ago? I told him the title, and he took out his phone, typed something into it, and said with a malicious smile, There’s no such book.

The deeper he involves himself in the living version of his old story, the more marginal he makes himself.

The novel’s brilliant twist on the doppelgänger trope begs a general interrogation of the conceptualized “original,” which can be extended to the act of translation. In Christoph’s case, his story has its own life and struggles to free itself from its origins. By his own standards a failure, neither a writer nor a lover, Christoph must choose between his story’s obsolescence and his own.

That’s when I noticed that my memories had changed . . . It felt dimly as though I could remember our Barcelona meeting, not from my point of view but his. An older man had told me his life story, and to begin with I had listened in disbelief that turned into the agitation you feel when patterns are crystallized out of life’s chaos, and stories emerge. Hadn’t this conversation in fact been the beginning of everything?

Despite some initial chafing, he lets go of his ownership of the narrative that’s defined his adult life. In the same way, when a translator, Hofmann for example, sits down to work, he troubles the reification of a story in favor of the intoxicating possibility of multiplicity.

The act of walking serves as a kinetic analogy to the theme of storytelling. Christoph and Lena’s central tour through Stockholm serves as a touchpoint as Christoph’s narrative diverges, each recollection sending him on a wander someplace else—in the mountains, for example, or “through the little crooked lanes” of Barcelona. Forward motion anchors us in the story more than time or place, so we don’t always know how to situate ourselves, which creates a vertiginous feeling, like walking during an earthquake. You don’t know if the ground will meet your foot when you put it down. Stamm and Hofmann, however, have precise control over the universe they’ve created. They know exactly where to divulge, where to suggest, and where to leave the reader to explore on their own.

Lena and Magdalena, depicted from Christoph’s perspective, have little personality of their own, but Christoph’s obsession with his own gaze proves to be his fatal flaw. “For the first time in my writing, I had the feeling I was creating a living world. At the same time, I could feel reality slipping through my fingers, daily life was getting boring and shallow to me. Yes, my girlfriend left me, but if I am to be honest I had left her months before in my imagination, I had slipped into fiction and my artificial world.” It is in Lena’s actions, not in her description, that we find her agency, rendering Christoph’s egotism absurd. Just as contemporary men have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of their patriarchal forefathers, Chris has the opportunity to live out an improvement on Christoph’s myopia.

This novel draws its energy from the powerful twin forces of love and shame. The desire to go back and tell a loved one, or to be told, with clarity, how much you were in fact loved years after you’ve yielded to your doubts. The possibilities, though indefinite, are irresistible. And that, one could argue, makes a living story.

Lindsay Semel is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: