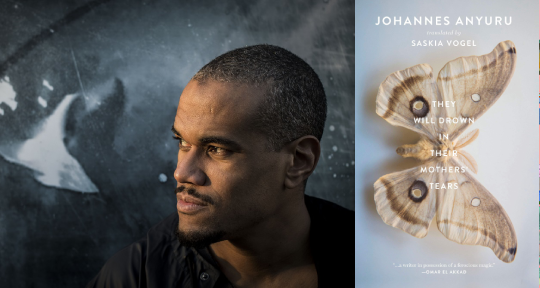

They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears by Johannes Anyuru, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel, Two Lines Press, 2019

As I’m reading the English translation of Johanne’s Anyuru’s They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears at the end of 2019, a news report catches my attention. The Sweden Democrats, a right-wing populist anti-immigration party with increasing support since entering the Swedish parliament in 2010, has proposed limiting the access to Swedish public libraries. Non-citizens in Sweden would lose their right to borrow books or use other library services. I’m talking about a proposed bill in the real Sweden, in the real now.

Terrorist attacks have become a familiarity in western European cities over the past years, and that’s starting to be reflected in the fiction that’s published. Anyuru’s latest novel starts with a bomb attack at a comic book store in Gothenburg. While this is fiction, there are clear references to both the Parisian publication Charlie Hebdo and the controversial Swedish artist Lars Vilks.

It was five years ago, in January 2015, that the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo was attacked by terrorists. Twelve columnists, editors, cartoonists, and other workers in the building were killed and eleven more were injured. You might remember the Je suis Charlie manifestations that followed across multiple countries. Probably less known around the world is conceptual artist Lars Vilks, a survivor of several targeted attacks, including the February 2015 attack in Copenhagen that killed one person. Lars Vilks has lived under death threats since 2007 because of his depictions of the prophet Muhammad.

Anyuru, a writer of numerous books of poetry, prose, and plays, had an international breakthrough with the 2015 novel A Storm Blew in from Paradise. At the onset of They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears, he picks fragments from both Charlie Hebdo and Lars Vilks when he creates the fictive Hondo comic book store and the artist Göran Loberg, the main target of the attack. Anyuru doesn’t shy away from complicated issues—instead, he utilizes a complex story structure to take us right to the core of them.

They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears is told through two narrators. There is the girl, one of the terrorists, who is called Nour, even though she claims to be someone else. The authorities identify her as a Belgian girl named Annika Isagel, a convert to Islam at fourteen, who had been previously detained at al-Mima, a prison located in Jordan and run by a security company with interests in Europe. Her passport states that she is Annika, her parents recognize her as Annika, but the girl herself claims to have nothing to do with the Belgian girl, and no one can explain how she is able to speak Swedish.

The girl called Nour survives the attack at the bookstore and ends up in the criminal psychiatric clinic Tundra. While there, she begins writing down her story and what she believes to be her background. By giving us the story through her—one of the terrorists’—perspective, Anyuru draws us into the complexities beyond the black and white of who is good and who is bad, even when it comes to terrorism.

The girl, however, is not the only narrator in this story. She requests to meet with a writer, the novel’s other narrator, who is a young man with a small family. At first, he doesn’t understand what she wants out of their meetings, though he assumes that she wants him to write a book about her. As they begin talking, however, he finds himself more and more curious of the girl and her story, and so continues to see her. The lack of a clear purpose of their meetings becomes less important to him.

Throughout the book, I often find myself confused as to which narrator is speaking; sometimes it takes a few sentences into a new chapter before I realize that the perspective has switched. Considering Anyuru’s close attention to detail in every other aspect of the narration, I’m inclined to think that this hint of a merging between the two characters is intentional. The medicated girl whose life is so difficult for everyone to grasp, and the young writer-father who detests her acts of terrorism—they seem so different, yet both are Muslims in a Sweden that perceives them with suspicion.

Though a complex story, the novel is not particularly long—not even three hundred pages. Anyuru applies a poet’s sense for the weight of each word as he builds the story:

“Back off!” / It happens first in her head. / She wants to tell Hamad to get down. / Click on the link to watch the video … The body is on its back, arms and legs flung out, breathing fitfully through its mouth, face swollen, bluish. / She thinks she sees a moth, large as her palm, crawling over Hamad’s face.

There are succinct, sometimes terse sentences where each word matters, along with swift jumps between focuses, thoughts, perspectives, or timelines. And then the continual application of seemingly symbolic devices like the moth, or snow in summer, or a willow tree. I don’t recommend skimming.

It’s not just the alternating narrators and sometimes abrupt switches that cause confusion. The timeline is—the timelines are—a challenge to keep up with, because here is the thing: the Tundra girl claims that she comes from the future. “I no longer think time is a straight line,” she says. As threads from her future become linked to the writer-narrator’s present, the different points in time become harder to distinguish. Add to that how this all connects to my present reality as reader—the confusion is unsettling in multiple ways. It’s one thing to read a dystopia, but another to see how well it fits with our own present.

The girl’s story—the one she is writing while hospitalized and that the writer keeps reading—describes a Sweden about fifteen years after the comic book store attack. This is a place and time where people who are not considered Swedish can be questioned by anyone, at any time. If they refuse to sign a contract, they are declared enemies of Sweden and forced into a ghetto, the Rabbit Yard. Her claim to come from the future, of course, is hard for the writer to accept, but still, there is something about her and her story that he can’t let go of. He continues investigating what he can about her: the comic book store, Annika Isagel’s family, the al-Mima prison, the area called the Rabbit Yard. He tries to make sense of her situation, to figure out the logical explanation of how the girl who says she is not Nour and not Annika has ended up where she is.

In her translation of Anyuru’s novel, Saskia Vogel pays as close attention to language as the writer himself. The English version of the book stays very true to the Swedish original and doesn’t deviate unnecessarily. The only time I’m thrown a bit by thinking about the translation is for a moment during the initial terrorist attack. The phrasing of “his train of thought is interrupted by an indistinct cry that comes from a man in the crowd, he or wha… or maybe he’s screaming gun in English?” forces me to start thinking and comparing the two languages. The Swedish han (he) and va… (what) copies the sound of the English gun in a way that the English he and wha… doesn’t, but I guess even if other words had been chosen for sound, the “in English” would have thrown me off slightly anyway. I might have personally opted for another solution, but I understand the reasoning behind this choice—other than this one instance, the English feels so close to the Swedish version I almost forget I’m not re-reading the original.

This is an intricately woven story, written with a wonderfully poetic sense of language. The book was published in Swedish in 2017 and was awarded the August Prize, the most esteemed literary prize for Swedish literature. In a time and place where things previously thought of as impossible—like the Sweden Democrats becoming one of the largest political parties in Sweden, and legislative proposals include limiting public library access only to those considered “Swedish enough,”—it might be a good time to question what is perceived as realistic and what is not. Sweden is a country that often thinks of itself as “multicultural.” There are those of us who like to think of multiculturalism as a positive asset, and then there are those, like the Sweden Democrats, who believe that multiculturalism is the cause of everything they find problematic in our society. What we have in common is the idea of Sweden as multicultural. With this important novel, Anyuru lets us see, from the inside, how far away from that ideal (or if you prefer to call it something else) we really are—and how close to the unsettling life of the Rabbit Yard we already are. These are scary times, and Anyuru helps us think about that.

Eva Wissting is a Swedish writer, editor, and creative writing instructor who currently studies English literature at University of Toronto. She is an editor for the Toronto-based Hart House Review, the Swedish poetry journal Populär Poesi and serves as Editor-at-Large to Sweden for Asymptote.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: