On June 9, 2019, more than 1 million people took to the streets to protest an extradition bill proposed by the Hong Kong government. If passed, the bill would make it legal for Hong Kong citizens to be extradited to Mainland China and tried under Chinese law—a legal system that not only threatens Hong Kong’s rule of law, but is also known for repeated human rights violations. Given China’s steady encroachment on Hong Kong since 1997, the “one country, two systems” policy that guarantees Hong Kong’s autonomy until 2047 is undeniably in jeopardy. The city’s concern over its future continually manifests in its local discourse, protests, and literature.

Although I grew up in Hong Kong, my interest in translating Hong Kong literature blossomed in Chicago, where I was studying English. Reading the work of Hong Kong writers allowed me to see my home city in a new light. One of the first Hong Kong poets I came across was Chung Kwok-keung, who writes about Hong Kong people, places, and politics with an attentive and empathetic gaze. In December 2014, he wrote a suite of poems (two of which were translated by Emily Jones and Sophie Smith for Asymptote) titled “Occupy Stories” about the Umbrella Movement—previously the biggest protests in Hong Kong in recent years. Now, with protests taking place again in the city, Chung is writing with an eye towards how the anti-extradition movement has shaped society.

I was not in Hong Kong when the protests began, so Chung’s poems became a unique way for me to connect with what was happening back home aside from relying on family, news, and social media. Since June, I have translated a number of his poems about the protests into English; two in particular, “When Yuen Long’s Main Road has lost its refuge islands” and “Beneviolent Force,” are strong examples that demonstrate how Hong Kong poetry reflects the city’s protests.

In his poem “When Yuen Long’s Main Road has lost its refuge islands,” Chung maps out key sites of conflict during the 2019 Yuen Long attack, an incident that shocked Hong Kong: on July 21, a mob dressed in white attacked protesters and civilians in Yuen Long. The “Main Road” that appears in the title of Chung’s poem is what locals call the Yuen Long section of Hong Kong’s longest road, “Castle Peak Road.” “Refuge islands” are raised platforms placed in the middle of roads to facilitate pedestrian crossing. As Chung explained to me, these refuge islands have been gone since the 1980s. In this way, the notion of safe passage on Hong Kong’s longest road (perhaps even preceding the road from 1997 to 2047) has long been in question. The physical identity of the city is analogous to its political reality.

| When Yuen Long’s Main Road has lost its refuge islands

When Peace Road is no longer peaceful When Teaching Road teaches us nothing Thin streets use a broad power To teach police batons, shields, vanished warrant cards How to stand up like people Rotten to the point where Winning Way shuts its door All that could be sold out has been sold out clean What is left in Forever Fragrant When tear gas bullets, rubber bullets, sponge bullets Bloom on the chests and heads of reporters When the officials crawl into their shells When the elderly are at the frontlines When the West Rail Line’s lobbies are welcome Wonderlands for Village dogs and the Raptors True Luck Street feels too long Blood is not so close to freedom Happy Together Street is for the police’s PR speeches White shirts prefer dark nights Flashes don’t come from stray fireflies Now blood enters our vision Heads become specks When Yuen Long’s Main Road has long lost refuge islands |

當大馬路沒有了安全島

當安寧路不再安寧的時候

當教育路教育了人們什麼

瘦瘠的街道以坦蕩的力量

教育警棍,盾牌,消失了的委任證

怎樣才能站得像個人

腐爛到了一個點

榮華便關上門

可以出賣的都出賣淨盡了

還有什麼東西在恆香

當催淚彈,橡膠彈,海棉彈

喜歡在記者的胸膛與腦袋上開花

當高官在龜隱

當老人在前線

當西鐵車站大堂是永遠開放的歡樂天地屬於村狗和速龍

泰祥街感覺太長了

血和自由之間沒有那麼短

同樂街讓給警民關係組的開場白吧

白衣人都喜歡黑夜

反光的不是迷失的螢蟲

到了連目光也見血

頭顱點點

當大馬路早沒有了安全島

7/28/2019

The poem is structured around actual roads in Yuen Long, the official English names of which are transliterations; for instance, 安寧路 is transliterated as “On Ning Road,” while 教育路 is “Kau Yuk Road.” However, the sonic doubling and wordplay in Chung’s poem would not be evident to an English speaker if they did not know what the road names signify: 安寧 means “peace,” and 教育 means “education/teaching.” As such, local street names take on a new life in translation (if you type “Peace Road” into Google Maps, you won’t find the actual street). For similar reasons, I also translated the names of the two iconic bakeries mentioned in the poem, Wing Wah (“Winning Way”) and Hang Heung (“Forever Fragrant”), even though their transliterated names are commonly used in Hong Kong. I was not able to exactly replicate the effect of all of Chung’s wordplay, however; for instance, the line “True Luck Street feels too long” is striking in the original because “True Luck Street” (泰祥 “tai cheung”) and “too long” (太長 “tai cheung”) are homonyms. Multiple puns in the poem reveal a city in crisis, posing the question: what does one do when familiar places no longer live up to their name?

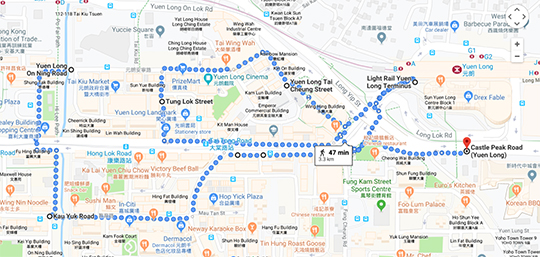

In her essay “The Poetics of Dislocation in Natalia Chan’s Poetry,” the scholar Esther M.K. Cheung argues that “the inclusion of general names and proper names is instrumental in giving verisimilitude to literary texts and establishing a cultural and historic setting…. Chan’s poems typify the close relationship between place-writing and place-naming in an urban context.” Both Chan (better known as “Lok Fung”) and Chung’s place-naming show us that the topography of the city reflects its times. In encountering their work, we are invited to read the city by walking the poem—which one may even do literally by mapping out the poems’ various locations:

Chung’s use of wordplay is even starker in the poem “Beneviolent Force,” in which he alludes to slang words that have taken root since the protests started. The title of the poem, 克警, is a nickname that Hongkongers have given to the Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF). 克 stands for 克制容忍, a phrase that police use to describe themselves; it means to exercise restraint, to be tolerant. At a time when police violence has been so visible in Hong Kong, it is of course deeply ironic that the police would call themselves tolerant or self-aware. 克警 is a homonym of 黑警, which literally translates to “black police,” what we would call a “bad cop” or “dirty cop” in English. I wanted to come up with a similarly oxymoronic title: thus, “Beneviolent Force” (a pun on “benevolent force”).

| Beneviolent Force

1 How gentle And wistful Is the brave man: Reporter my ass, motherfucker 2 All crows are the same shade of Bumping heads ‘til you’re blue and Tracing a darker and darker 3 The dogs have also come out To break ties with those animals 4 Don’t wave your nightstick around Even if you don’t show it We can all see Your withering cards 5 Officers buried in the Gallant Blossoms: Oblivious to the Han Dynasty Let alone the Yi Jin |

克警

1

多溫柔

念舊的

男子漢:

記你老母

2

天下烏鴉一般

頭頭碰著

越描越

3

狗也出來

跟牠們割蓆

4

別亂揮警棍了

即使不出示

我們都看見

你的萎荏症

5

浩園記:

乃不知有漢

無論魏晉

7/9/2019

What is striking about “Beneviolent Force” is the way in which it upends our understanding of commonplace phrases. Stanza 1 ends with 記你老母, a derivation of the common Cantonese curse 屌你老母 (“fuck your mom”). 記你老母 went viral when a cop used it against a man who said he was a reporter (記者); the police didn’t believe him and fired back with the curse. In stanza 2 of the poem, which was one of the most challenging parts to translate, the word “black” (黑) is removed from three idioms: 天下烏鴉一般黑 (“every crow under the sky is the same shade of black”), 頭頭碰著黑 (literally “heads bumping into black,” i.e. always running into bad luck), and 越描越黑 (“the more one traces, the blacker the picture becomes”). By absenting the final, crucial word “黑” from the poem, the poem perhaps mimics what the police themselves are doing: removing mentions of their corruption from the narrative. In Stanza 4, 萎荏症 (literally “flaccid/withering disease”) is a homonym of “warrant cards,” which the police have notoriously failed to show on multiple occasions. In Stanza 5, Chung alludes to “Gallant Gardens” (浩園), the cemetery where public officials (including the police) are buried in Hong Kong. 浩園 is phonetically similar to The Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源記), a classic Chinese tale about a secret utopia. The utopia’s villagers sought refuge in the Peach Blossom Spring during the Qin Dynasty and stayed there ever since, oblivious of the Han (漢) dynasty and the Wei and Jin Dynasties (魏晉). The police of the past who are now buried in Gallant Gardens are like the fable’s villagers—blissfully oblivious to the chaos reigning outside, wreaked by their fellow men. Moreover, 魏晉 is phonetically similar to “Yi Jin,” a term that has been used to denigrate police officers (the term derives from the Yi Jin Diploma programme, which is typically pursued by students who do not perform well academically).

Wordplay, and the act of translating it, is meant to be playful, and yet “Beneviolent Force” feels like a lament. Through language that subverts our preconceptions of familiar phrases, Chung shows how the city’s impression of the police has undergone significant change since the protests started. A once-trusting relationship has evolved into deep resentment and fear following demonstrations of police violence; indeed, one of Hong Kong protestors’ “Five Demands” is for there to be an independent inquiry into the HKPF.

What’s significant about both “When Yuen Long’s Main Road has lost its refuge islands” and “Beneviolent Force” is that their puns only exist when the poems are read in Cantonese. One would also have to know some of the slang used by protestors to recognize them in the poems—these words come straight from the streets into the lyric. Today, Hongkongers are inventing new words (journalist Mary Hui unpacks many of these phrases in this illuminating Quartz article) not only to express themselves, but also to survive. By communicating in a secret language, protesters have a better shot at evading police; by communicating in Cantonese, they keep Hong Kong’s local language alive.

As someone whose Cantonese is rusty and who was not in Hong Kong when the protests were at their peak, I did not have an easy time translating Chung’s poems. Understanding all the references involved doing research and communicating with Chung, whose feedback not only informed my understanding of translation, but also of Hong Kong. One of the main reasons I translate is to better understand the place I come from—and that process takes work. The discourse surrounding Hong Kong protests is complicated, as is the effort to translate it to different audiences.

Since the protests began, Hongkongers have taken up a famous quote by Bruce Lee as their motto: “Be water.” The full quote is as follows:

“Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water my friend.”

Aren’t translators also like water? Don’t our voices also adapt to fill the shape of whatever text we’re translating? Translation creates a powerful space for empathy, because you must write out another voice and adapt to it. You become like water, filling a cup and becoming the cup. When I translate a protest poem, I understand more about the real work of protest happening on the ground. So, perhaps it is because of the challenges posed by translation that I find it one of the most productive tools for facilitating understanding. Aside from translating Chung’s poetry, I also contribute to Hong Kong Columns (Translated), which translates local news articles that do not often receive mainstream English coverage. I’ve also translated for Lausan, a collective committed to “sharing decolonial left perspectives on Hong Kong.” Lausan welcomes translators working with multiple languages, and recently shared an article translated into Indonesian. If you are a translator or are interested in translation, you may find both productive platforms for engaging in Hong Kong politics. It is also important to keep an eye out for translations of Hong Kong voices on the protests, such as Andrea Lingenfelter’s recent translation of Hon Lai-chu’s essay “Hong Kong’s Sickness,” or Jacqueline Leung’s translation of Stuart Lau’s fiction in the Fall 2019 issue of Asymptote. The writer and translator Tammy Ho-Lai Ming has also been actively writing poetry about the protests since they began.

In a recent essay for Zihua Magazine, Chung wrote: “Poems should respond to their times. Poems should have humanity. I have always insisted upon this in my work.” The same can be said about translation, which is its own form of activism. Through shining a light on Hong Kong voices, I believe that advocates of Hong Kong literature can show the world that the city is worth fighting—and translating—for.

May Huang is a translator, poet, and essayist. Born in Taiwan and raised in Hong Kong, she graduated from the University of Chicago. Her work has appeared in Exchanges, InTranslation, Cha, and elsewhere. She was previously a social media manager for Asymptote. You can find her on Twitter as @mayhuangwrites.

*****

Read more essays on the Asymptote blog:

- Dispatch from PEN Hong Kong: In Conversation Jason Y. Ng

- Hong Kong, My Home

- The Day Got Hit on the Head With Books by Chan Koonchung

And don’t miss the following highlights from our Fall 2015 issue: