Winner of France’s Prix Roger Nimier in 1973 and now published for the first time in English, this month’s Book Club selection is a powerful portrait of childhood and the struggle between freedom and nostalgia. Written by Inès Cagnati, who was born in France to Italian immigrants, Free Day vividly depicts feelings of estrangement within a community and the surrounding environment. Through the interior monologue of fourteen-year-old Galla, Cagnati poignantly conveys the conflicts of childhood experience: hostility, fear, cruelty, yet overwhelming curiosity and desires.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

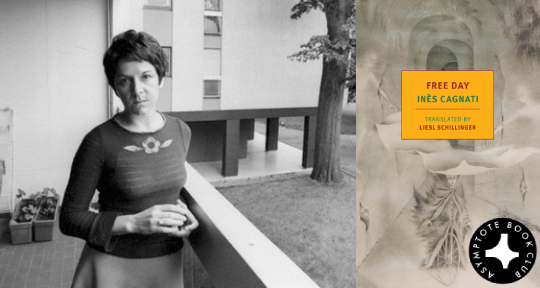

Free Day by Inès Cagnati, translated from the French by Liesl Schillinger, NYRB, 2019

In Free Day, Inès Cagnati—with evidently great subtlety and focus—examines a young girl’s manner of interacting with the world around her, in addition to developing that which lies within her. Though the basis of the book is that of a poor Italian family of farmers in mid-century France, the novel is in actuality a character study of fourteen-year-old Galla, chronicling the sacrifices she makes in order to attend high school.

Initially, the reader senses a degree of ambiguity regarding the narrator’s age before it is revealed, as Galla seems to pendulate between the thinking of a child and that of an adult—indeed as one does at that in-between age. Though by no means convoluted or rambunctious, here one could argue that there is something Joycean in Cagnati’s book, as the dramatic guise is stylistic in a manner that we have originally come to know and love in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Cagnati immediately sketches Galla not as bratty or melodramatic, as teens are sometimes written, but as a likeable freethinker despite her condition: “The English professor, too. He talks to us endlessly about people who’ve been dead forever, instead of leaving them in peace, which they definitely deserve, or telling stories of his own.”

In light of current events and “hot topics,” I am more inclined to believe that the book is less a metaphor for our current political situation (specifically Trump’s immigration policies) and more about the universal and unfortunately never-ending trappings of poverty. This is reinforced by the fact that the status of “foreigner” is only barely touched upon, and that no language besides French is spoken or even mentioned in the book. The memorable essence, however, is far removed from all of this; it’s precisely where philosophical transcendence interweaves with the narrative that the book becomes an object of interest, given Galla’s unique worldview.

When we went back into the house, we saw all my sisters silent and motionless, their mouths open in song. We buried them all together in a box made from the wood of a poplar my father chopped down for the purpose. Now, on windy nights, when there has been a lot of sun, and the strong fragrance of syringas and flowering vines fills the countryside, you still can hear my dead sisters singing.

Cagnati is not afraid to create a paradoxical protagonist, bringing her a step above the archetype she represents—that of the seraphic “little match girl” character that we encounter in Emilia Pardo Bazán’s “Las Medias Rojas” or Joyce’s own “Eveline.” Though sensitive and thoughtful, Galla is as sassy as a real teenager: “And if they are the last to laugh, as I suspect, they’ll be laughing under the humps on their backs. That consoles me. Only a little.” Of course, Cagnati departs from obvious sources of inspiration by bringing things closer to and clearer than conventional writing. There are times when the novel reads like advanced YA fiction, while at other moments it is profoundly lyrical in a classic style:

Because we live in the heart of a land choked with wild waters, where strange, mute flowers grow, and ghost birds live that we only know by the cries we hear on the murkiest nights, and then there are those crazy mists into which the trees and our hills vanish; and, because we live in the middle of these watery lands without ever meeting anyone, I believe we no longer have any idea what life is like elsewhere, or if people and towns even exist elsewhere.

Lucidly written and rarely departing from its intent, the book feels like an exploration of complicated familial relationships, pervasive with senses of internalized guilt, complexes, and low self-esteem. Galla self-flagellates and dissociates, feeling sorry for her ugly dress instead of herself for wearing it. We readers, used to idealizing Arcadia, are reminded of the fear and constraint that can be a part of being, in a way, another person’s property.

One might suggest that there is more than meets the eye when one considers the Catholicism of the region and era, though this is never explicitly addressed. In a similarly clever fashion, things are spelled out in a language that becomes illusory, with the father first being portrayed as a one-dimensional villain, and later perhaps simply the product of his circumstances. Solitary, the narrator flexes her power of perception, troubling the reader as much as the ending eventually does. The psychological intensity is reminiscent of Herta Müller’s writing—being at times bitter and piercing and at other times swinging between oneiric and realistic, as Galla is overwhelmed by the strong emotions characteristic of her age.

Liesl Schillinger’s translation feels close to the French, retaining the deliberate awkwardness of the original’s particular syntax, as well as the narrator’s repetitive verbal ticks, mimicking an obsessive thought process. Even the cognitive dissonance that she experiences is apparent through her way of mixing the high register she learns at school with the low one that is characteristic of her origins. Subtle and unexpectedly profound, Free Day absolutely has its place in the NYRB corpus.

Andreea Iulia Scridon is a Romanian-American writer and translator. She studied Comparative Literature at King’s College London and is currently studying Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. She is an assistant editor at Asymptote Journal and The Oxford Review of Books.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: