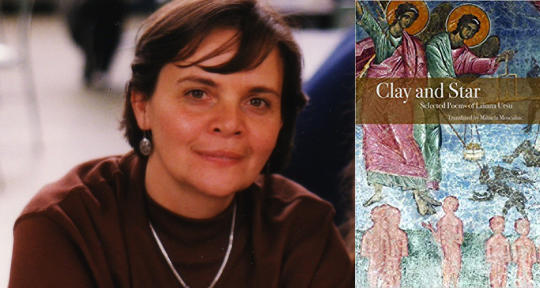

Clay and Star: Selected Poems of Liliana Ursu, translated from the Romanian by Mihaela Moscaliuc, Etruscan Press, 2019

With an impressive record of thirteen collections in Romanian and five collections in English translation, it is no wonder Liliana Ursu has now arrived with a generous (over seventy pages) collection of selected poetry, published by Etruscan Press in Mihaela Moscaliuc’s translation.

It is just that, unlike your usual (American) volume of selected poetry, the book does not divide the poems by their appearance in previous collections, but simply lists their titles in the contents, every now and then mentioning under their last line where and when they were written. Other poems mention the location in the very title—Văratec Monastery in northern Romania, for instance, is both frequently present and representative of the poetics, but Sibiu, Bucharest, Boston, and San Francisco also appear—while others are dedicated, in their epigraphs, to people met in those places. The book thus amounts to a sort of journey that, while capturing fleeting specifics of literal locales in snapshots, is most prevalently a progress of the soul.

The confessional therefore sets the tone, but is at the same time placed in multifaceted perspectives that render the speaker both observant and observed. The title of a poem meaningfully speaks—for instance—of the “poem composed while being watched by a bird.” The multiple angles are accompanied by a functional synaesthesia that brings together the senses and speech alike.

Let your soles touch the grass

gracefully, as in childhood,

when you swam among stars.

Let your step be soundless,

and wordless your glance.

Walking barefoot in the grass, with its rich, occasionally ancient, references (in the way that Plato’s speculations on love find a different scenery than his usual urban settings, far away while treading the grass) mark a decidedly tactile intro. But unlike in, for example, modernist Lucian Blaga, instead of bringing about Dionysian frenzy, this occasion is a more feminine, motherly initiation—

To hush your headaches,

bare your feet and tread the grassas if learning your first words

on mother’s lap.

Mother Nature teaches us how to speak, yet its rustling manifold presence also takes us beyond. Its multiple angles conjure angels: “. . . while angels’ lips / teach you once more / how to pray.” While far from being as metaphysical as the above-mentioned high modernist Blaga, Ursu still shares with him in a long Romanian literary tradition of a deep yet immediate familiarity with the sacred, and particularly with angels (in Blaga’s terms, “cerul megieș,” “the neighboring heaven”). A contemporary voice, Ursu is less of a philosopher, but her simultaneously ethereal and acutely sensorial approach allows her to lodge the (at times decorative) sacred in confessional contexts and briefly sketched locales, which brings her closer to other modernists, notably Ion Pillat, contemporary poets like Adrian Popescu (who has actual recollections of a specific locus he identifies as paradise), and the practicing theologian Ioan Pintea (who charts esoteric eastern orthodox tradition and Transylvanian village life alike). Her topography is more mobile and diverse, however, reflecting not only her international trajectory (she is a two-time Fulbright grant recipient) but also her (in Pierre Joris’s terms) “nomadic” sensibility and the minimalist touch shared with kindred women writers such as Mihaela Moscaliuc, the translator herself, and another internationally known and awarded Romanian poet, Ana Blandiana.

Moscaliuc, also a Fulbright scholar and a gifted poet and translator in her own right, is not concerned in her brief preface with any such Romanian connection, kinship, or filiation. She prefers instead to speak of the connectivity between the poems themselves, and the way in which they “connect vast territories and cultures . . . into spaces of spiritual intimacy.” It is perhaps this spiritual determinacy—“unabashed” indeed, as Moscaliuc calls it—that will most likely strike the American reader. A poetry so incessantly and unequivocally speaking of prayer (“honey of prayer” reads a representative line), conversing quotidianly and candidly with angels, and undauntedly evoking the (capitalized) Him (and “His light”) has—in spite of praises coming from towering figures such as Mark Strand, cited by Moscaliuc in the preface—a significantly distinct tone and diction from what one can usually find in a mainstream collection and in the dominant (MFA and literary journal) culture.

There are still poetries available in translation with relatively similar dictions, particularly the ones coming from the middle east. A collected poems of Yehuda Amichai, for instance, released a couple of years ago, may have baffled (unwarned) readers with a defiant voice in which words like “prayer” and “God” made similarly leading features, even if the tone was now and then strikingly unorthodox (when not downright heretic). Mahmoud Darwish, another major example, has been a consistent presence, and so has been his American curator, poet Fady Joudah. Still, Liliana Ursu originates from a different region that, in spite of post-communist turmoil, is past its recent historical catastrophes, soviet invasion, and Nicolae Ceaușescu’s subsequent rule (even if the latter’s ghost still haunts our memory, Romanian politics, economy, and demographics, and does therefore inevitably shortly resurface in the book’s preface as well).

Ursu comes, in fact, from a different kind of war zone—that of the personal apocalyptic journey. Sounds grand or antiquated? Not in her voice. She has no dogma to measure against historical disaster (unlike the middle-easterners above), as she is, for lack of a better term, a Christian universalist, effortlessly uniting eastern orthodox and western traditions and aiming not so much for the ideology as much as for (in the words of a major contemporary mystic), the “experience of God.” She does not live and write, in Adorno’s famous phrase “after Auschwitz”, so much less so than in Jerome Rothenberg’s Khurbn, in which poetry becomes possible again even after Auschwitz by dealing frontally, most explicitly, and even horrifically with the otherwise unspeakable literalness of modern genocides. No, Ursu, improbable as it may sound, comes from… beyond Auschwitz, from… Patmos (the place where perhaps the most celebrated apocalyptic vision was recorded), while actually directly referencing St. John’s Book of Revelation.

Consequently, the cross is not a symbol, but an actual path, a non-evasive way out—“the only stairs in the stairless hotel: / a crucifix” (poet’s emphasis). Relevant (and revelational) experience reaches therefore the brief and imagist aura of haiku:

At times I’m a scythe in a lonely woman’s hands,

other times the wild strawberry

on the mountain path.

Being mystical in Ursu’s case, though, does not mean “not of this world.” Quite on the contrary. Some of her most accomplished effects are, in fact, triggered exactly by a keen eye for details. She is spiritual within and by means of the mundane, and her ear seems to thrive best in briskly fresh, suddenly remembered—if intimately mediated—minutiae. A street corner, the name of a pub in her hometown, regulations in war time (as recounted by parents), haystacks and monastery walls at night, marketplaces in San Francisco and Bucharest rendered adjacent by the sight of a cabbage (and the poet’s meandering sensory memory), etc. Only long, silent, patient, and focused respites spent really close to things—little, prosaic, “insignificant” things—will perhaps spawn such indelible images:

Night sleeps in the village darkened by rain

like a key

rusting on the floor of the sea.

Mihaela Moscaliuc has masterfully brought us this key from Liliana Ursu into the English language, a small yet resilient key that might take us through the dark, corrosive, and relentless rain of our time.

MARGENTO (Chris Tănăsescu) is a transnational gypsy, half Romanian half Moldovan, half Romanian half Romanian, nationless immigrant. World-waste/neural-network cyber-poet, cross-artform multimedia busker, math maniac, teacher. Lover and father.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: