To live, to remember, and to forget—these are the mainstays of nearly every narrative both real and imagined, and this month, we have selected Burhan Sönmez’s masterful novel, Labyrinth, which traverses these themes with a lucidly Borgesian, yet stirringly original hand. A highly anticipated publication in Sönmez’s award-winning body of work, this profound book navigates the psychogeography of Istanbul to interrogate that most mysterious creature: the self.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

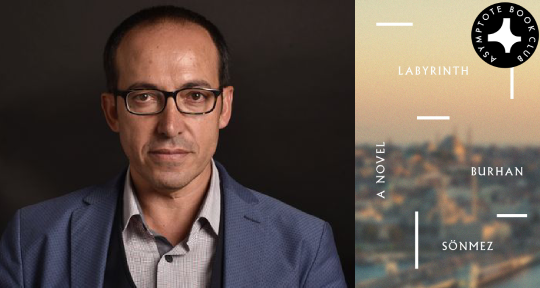

Labyrinth by Burhan Sönmez, translated from the Turkish by Ümit Hussein, Other Press, 2019

Boratin Bey knows that his name is Boratin, that he lives in Istanbul, that he is a blues musician with a tattoo on his back, but he doesn’t know why. And, more urgently, he doesn’t know why he jumped from Bosphorus Bridge—a fall he survived but which has now caused total memory loss. At the beginning of Burhan Sönmez’s Labyrinth (deftly translated by Ümit Hussein), Boratin wakes, disorientated in his unfamiliar apartment with no knowledge of who he is. Luckily, he has a few anchors that can guide him through his now estranged surroundings. Firstly, his bandmate, Bek, who takes care of practical matters, informs him of his likes, dislikes, habits and tries to settle him back into his old rhythm. His sister helps as well, taking great joy in remembering the past and recounting tales of his childhood to Boratin over the phone.

His experience of the world may only just be commencing, but it doesn’t take long before the big philosophical questions start to appear. “Did I choose and buy the furniture in this house?” and “Have I always lived alone?” are suddenly supplanted by “What does beautiful mean?” and “What brings on the desire to die?” A change that is, of course, understandable as Boratin is suddenly forced to step into his own life through the eyes of a complete stranger to it.

Sönmez’s most recent novel, highly anticipated after the publication of Istanbul Istanbul (2015), is a vertiginous exploration of identity, memory, and history, and translator Hussein’s English prose is both dreamlike and profound. The early shift in narrative form from the first person to the third introduces a masterful weaving of perspective, voice, and time. It is no surprise that the two epigraphs to the book relate to Borges; the pervasion of clocks, mirrors, dreams, libraries, and mythology (not to mention the title!) are a clear homage to the Argentine writer. Without his memory, Boratin’s knowledge of the world is not always bound by physical laws, and as his identity continually slips away from him like a mirage, so too does reality swim and refract: “Can the opposite of dark be sound?” he asks at one point, allowing the reader to experience Istanbul and its inhabitants through this synaesthesia.

The novel begins with the ringing of an alarm clock and before long, Boratin has set out to purchase a new clock from a watch seller. Within each of Boratin’s fresh encounters with the inhabitants of the city, Sönmez embeds layers of different narratives. From the watch seller, we hear anecdotes of his grandfather who claimed that the three greatest human inventions were the clock, the mirror, and . . . well, he (fittingly!) can’t recall the final invention. From the grocer, we hear the tale of a young man and an old man who must help a woman to cross a river. The young man carries her across on his back whilst the older man disapproves of this: “customs state that touching a woman is forbidden.” The whole narrative is woven together with such moral fables, as traditional wisdom and knowledge are passed on through storytelling.

Yet, as in the clash between the old and the young man, this is a novel where tradition and novelty collide. Boratin exists as two people: the person who existed prior to his fall, whom the city and those around him are familiar with, and the person who survived the fall without his memory, who must decide between rediscovering and recreating himself. “New books are cheap, old ones expensive. In life, too, old time is more important. It’s yesterday that’s valuable, not today, and the day before that even more so.” In this exploration of the passage of time, Sönmez is at his most philosophical and his most political. Recurrently throughout the novel, the value of remembering the past is challenged: “Boratin, you have freed yourself of your past, losing your memory has set you free,” one character says to him, while another patient in the hospital ponders to him that: “maybe you are unfortunate to still be alive and fortunate to have lost your memory.” Boratin is afraid of his past, afraid of what he might discover if it all one day comes flooding back to him.

Yet Sönmez makes a clear distinction between the past and history. Boratin can still recall many landmark events—the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the crucifixion of Jesus—but he cannot place them within a clear historical time frame. Similarly, he can recognise landmarks in Istanbul but has no indication of their relevance or history. It is only in their immediate impact upon him in the present that history comes to life once again. He is fixated by a small statue in his apartment of the pietà, and is moved deeply by the simultaneous sorrow and tranquility on Mary’s face. That he had never shown any regard for it prior to his fall becomes irrelevant—his recognition of human suffering and its impact on him in the present has made its history relevant and alive once again.

The novel’s setting, Istanbul, is also integral to the exploration of such themes. It is a city where ancient and modern, East and West, the religious and the secular coexist, and from Boratin’s apartment we witness such variety: views over Galata tower, the rooftops of Topkapı Palace, Beyazıt Tower, Balat Hill and, on the other side, concrete walls, “cats and dogs instead of birds,” and piles of rubbish. Many important scenes take place at the border between Asia and Europe—Boratin jumped from Bosphorus bridge whilst crossing over to the European side, and the novel ends at the abandoned Haydarpasa railway station at the beginning of Anatolia. Sönmez, who was born in a Kurdish village in Turkey before moving to Istanbul, and who now divides his time between Cambridge and Istanbul, reveals the importance of place, specifically through these meeting points, areas of encounter and possibility.

One final meeting point integral to the novel is between the body and the mind. As Boratin says: “Memory loss doesn’t count as bodily injury.” Yet a question that hounds him is what caused him to throw himself from Bosphorus bridge. “What can be worth dying for? Was there anything that valuable in my life?” As he searches for clues, and as nobody can remember any cause or indication behind Boratin’s jumping, we are asked to question how well we can ever know anyone. How much is physical recognition ever worth, and to what extent can it truly define us?

Sarah Moore is a bookseller and editor from Cambridge, UK. She currently lives in Paris and is an Assistant Blog Editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: