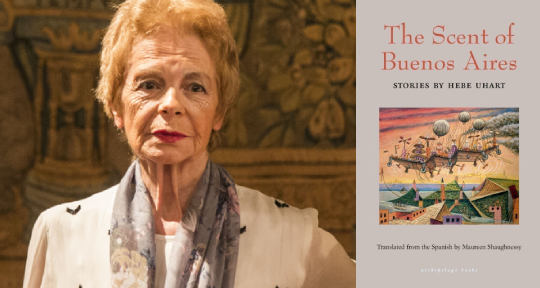

The Scent of Buenos Aires by Hebe Uhart, translated from the Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy, Archipelago, 2019

Hebe Uhart’s The Scent of Buenos Aires is a series of musings on the complex makings of place that embodies the spirit of this city, revealing a secret magic woven into the countless lives that buzz at its center. Her stories highlight mundane, quotidian experience—from dinner parties to rides on the subway—but the aura of each piece is tinged with the surreal, the uncanny, emanating a subtle strangeness unique to her characteristic voice.

Prior to her death in 2018, Uhart’s life was defined by her meticulous attention to the world and its inhabitants, a perspective that enriched her interest in literature and philosophy. Her authorial career spanned several novels, Spanish-language short story collections, and literary workshops; she also served as a professor of philosophy at Argentina’s National University of Lomas de Zamora for several years. Uhart’s work has won numerous accolades (including Argentina’s 2015 National Endowment for the Arts Prize) and is defined by its ambiguous narrators, quietly humorous characters who display a certain skepticism about the world and the fickle nature of life. Although her stories reverberate with rich description, intricate details, and lively personalities—often functioning as direct projections of her own lived experiences—plot is never of major importance, the absence of which renders her work somewhat still, devoid of much action or narrative thrust. Instead, Uhart’s concern is that of the particulars, the subtle ways that perception unfurls from a specific point of focus, and though her life was dense with movement and progression, her work invites us to pause and pay attention to how we, ourselves, perceive our surroundings.

The Scent of Buenos Aires is no exception to this trait. Translated by Maureen Shaughnessy, this collection is the first of Uhart’s work to appear in English, and her signature narrative style remains wholly intact. Peppered with colloquialisms and a conversational tone, each story offers an intimate glimpse into lives both strange and somehow familiar, a penchant that underlies much of Uhart’s writing. Uhart is regarded as one of the most renowned voices in contemporary Spanish-language literature, and her ability to convey wisdom through natural, accessible diction emerges brightly in this collection. For instance, the young protagonist in “Bees are Industrious” tells himself: “Everything that’s part of the human condition, that’s within my power, I’ll analyze on my own, in my own way. I’ll look at it from all sides. Whatever I can’t analyze . . . I’ll leave up to God.” While this affirmation applies directly to the narrator’s dream of priesthood, it also serves as an example of Uhart’s keen tendency to impart almost allegorical lessons onto the reader. The youthful voice of the narrator feels authentic, yet it is conveyed with a tactful maturity that resonates with an adult audience—Uhart’s characters often tread this line between innocence and incredible wisdom, her ability to balance simplicity and depth marking her deft narrative skill.

An avid traveler, Uhart’s ability to measure people’s perceptions of the world—and their place within it—is evident in The Scent of Buenos Aires, revealing an astute and intuitive understanding of the often conflicting nuances of human nature. In “Tourists and Travelers,” Uhart’s narrator expounds on the difference between the two, asserting that “a tourist is when you let yourself be led around like a sheep, and you don’t notice anything around you.” This claim highlights Uhart’s emphasis on observation, her reliance on the minutest of details to build a complete and authentic reflection of each character’s unique reality. Her remarkable way of revealing a character’s core through highly limited, casual language expands beyond the human realm, too, taking root in the plant and animal kingdoms. Here, she demonstrates the links between all living things; when describing a zany relative, for instance, the narrator of the titular story “The Scent of Buenos Aires” is shocked that Aunt Maria could grow “normal plants . . . [for] when the plants sprouted, they should have looked deranged,” a notion that reflects the idiosyncrasies of the person responsible for the plants’ survival. (Perhaps Uhart’s focus on flora is unsurprising, as she was known to have cited Felisberto Hernández in saying that “a story is a little plant that is born.”) Cultivating a sense of respect for (and kinship with) other levels of sentience, Uhart’s manner of acknowledging the interconnectedness of consciousness allows us to see Buenos Aires—any place, really—as its own organism, composed of endless living, breathing parts. Further, Uhart takes us into the internal worlds of these beings, shining light on both the typical and extraordinary ways we perceive our environment and ourselves.

This sense of communion and connectivity is embodied by the short story collection’s form. Argentine writer Inés Acevedo said of Uhart: “Hebe is the best and the strangest. After decades of writing and publishing narrations, Hebe became an author that dominated a central genre for the Argentine tradition: the short story.” While her work challenged traditional approaches to narrative, there is no question that Uhart was a maven of the genre, aptly utilizing the short story collection to formally convey the myriad content between its covers. Dense with tales that trail off into their own dimensions, The Scent of Buenos Aires is collage of sorts, a mosaic of experiences that coalesce into a greater shape, as Buenos Aires serves as a container for the individual lives of its myths and citizens, its flora and fauna. In this sense, Uhart demonstrates her mastery of the form/content relationship, her capacity to bend and mold language to mimic the makeup of life.

Overall, The Scent of Buenos Aires reaffirms Uhart’s almost indefinable place in South American fiction. A writer who supersedes genre, Uhart writes of very specific experiences that somehow function on a universal level, impacting readers through the grammar of allegory. Finally available to the English-speaking world, these short stories offer a beautiful bridge into existence as Uhart saw it, and Shaughnessy’s sharp and sensitive translation brings new life to these vibrant tales of Buenos Aires.

Leah Scott is a freelance writer and editor from Denver, Colorado. Her love of language has taken her all over the world—right now, she lives in Oviedo, Spain, where she is working on a long-form fiction translation project. She currently serves as Social Media Manager for Asymptote.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog:

- Teeming with Speech: Youssef Fadel’s A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me

- The Harmony of Normalcy: Wang Anyi’s Fu Ping in Review

- What’s New in Translation: November 2019