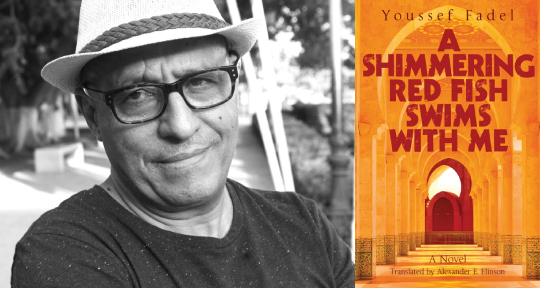

A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me by Youssef Fadel, translated from the Arabic by Alexander E. Elinson, Hoopoe, 2019

A massive construction project looms in the background of Moroccan author Youssef Fadel’s novel Farah (2016), beautifully translated from the Arabic by Alexander E. Elinson and published under the title A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me (Hoopoe 2019). The project in question is the building of Casablanca’s Hassan II Mosque, named after the Moroccan ruler who commissioned it. As Elinson explains in a concise and illuminating foreword to his translation, King Hassan II (r. 1962-1999) announced his plan to build a grand mosque on Casablanca’s Atlantic shoreline during his 1980 birthday celebrations. The mosque was inaugurated in 1993, on the eve of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday. Designed by a French architect and built by a French firm, the mosque project required the labor of over thirty thousand workers, including thousands of master craftsmen who carved, chiseled, sculpted, and formed its dazzling array of tile mosaics, stucco moldings, and decorative woodwork. The structure that emerged from this massive effort accommodates up to one hundred and five thousand worshippers, making it the largest mosque in Africa and one of the largest mosques in the world—but such grandeur comes at a huge cost, both financial and human. The mosque came with a whopping price tag of over half a billion US dollars, and much of the financial burden fell on Moroccan citizens, who were required to help pay for the mosque through a public subscription program. The project also upended life in Casablanca, particularly for the people who lived in the densely populated neighborhood that was razed to create room for the new mosque.

These upheavals are at the heart of Fadel’s novel, which explores the experiences of the Moroccans who both lived in the shadows of, and contributed to, the construction project, and who were eventually displaced to make room for the massive mosque that they had helped build. A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me is Fadel’s tenth novel and the final book in a trilogy about contemporary Morocco. The novel centers on an ill-fated love story between two young Moroccans: Farah, who escapes her hometown of Azemmour and comes to Casablanca to pursue her dream of becoming a singer, and Outhman, who works with his father as a carpenter at the mosque. The lovers’ fate is sealed in the novel’s first chapter, where we learn that Farah is the victim of a brutal acid attack, witnessed by Outhman. The rest of the novel is devoted to unpacking the events leading up to the acid attack on Farah. The story is told through an intricate narrative structure that unfolds along multiple timelines and from multiple perspectives, meting out information in suspenseful portions whose full meanings do not become clear until the last page. Each of the novel’s seven sections opens with a chapter narrated from the perspective of a third-person omniscient narrator located in the present, some twenty-three years after Farah’s death. The internal chapters of each section are narrated in the first person from Outhman’s perspective, beginning at the time he met and fell in love with Farah while working at the mosque’s construction site. The last chapter of each section is narrated in the first person from the perspective of another character in the novel, such as Farah or Outhman’s mother. The result is a kaleidoscopic view of working-class life in Casablanca, one that uses the tragic love story between Farah and Outhman as a launch pad for exploring the tensions running through Moroccan society in the 1980s and ’90s and, in particular, for laying bare the tremendous costs that the Hassan II Mosque inflicted on the people living around it.

The mosque is not just a backdrop or a silent witness to these stories but a living agent that shapes the trajectories of the people living in its midst. Fadel’s novel is deeply human and humane, but it also envisions a world where the human realm is porous and open to intimate connection with nonhuman actors. In Fadel’s hands, the entire nonhuman world is brimming with life, and even with volition. A pit bull cajoles, a crow feels smug, a giant excavating machine crouches, and a plastic bag dances in the wind while experiencing a rich range of emotions, from “brazen indifference” to “calm haughtiness.” In the second half of the novel, Outhman’s father, a master carpenter, points to the geometric designs that he has carved in the mosque’s ceiling and explains to a group of tourists: “There can be no humans or animals or anything else without the connections that tie them together. There exists nothing but connections, neither in the world of human beings nor in the world of objects.” Such connections drive Fadel’s novel: not only the connections between lovers, neighbors, or citizens, but also the connections between people and animals, people and things, and people and the places they live, work, and worship. In this novel, places and inanimate objects are not just passive vessels for human action; rather, they act alongside—and, in the case of the Hassan II Mosque, over—human action. Fadel’s characters are richly drawn, but so are his animals, machines, and stones. Perhaps on account of the novel’s attention to nonhuman animacy, one of Fadel’s preferred literary devices is onomatopoeia. In Fadel’s novel, the nonhuman and inanimate worlds teem with speech: a sewing machine goes tak tak tak, footsteps say taf taf taf, and a man and a magpie converse in tweets. Everything is talking, humming along in its own language.

Some of Fadel’s literary devices, such as his frequent use of onomatopoeia, are easy enough to render in English, but others require a very sensitive ear. Luckily, the novel is in expert hands with Alexander Elinson, who is a specialist in Moroccan literature and has already translated another novel by Fadel, A Beautiful White Cat Walks with Me (Hoopoe 2016). Take, for example, the imaginative strategies that Elinson deploys to render the novel’s use of popular idioms, slang, and song lyrics. In a chapter narrated by Outhman’s mother, the narrator finds herself humming the following lyrics: “The blanca, mon amour. I’ll marry her without any magic allure . . .” These lyrics come from the raï classic, “Baïda mon amour,” made popular by the Algerian performer Cheb Hasni. The challenge that the translator faces here is that Cheb Hasni’s lyrics not only playfully combine two languages (colloquial Algerian Arabic and French), but they also feature a translingual rhyme between the French mon amour and the colloquial Arabic word sḥūr (“magic”). Elinson’s creative and elegant solution preserves not only the rhyme but also the code-switching between languages. Here and elsewhere, Elinson’s translation conveys the playful diglossia and multilingualism of Fadel’s novel and of North African culture, in general.

Elinson’s translation also preserves a sense of place and cultural specificity without falling into didacticism. Although the novel is rich in cultural references and details that speak to the Moroccan context, Elinson does not offer explanatory footnotes. Instead, he lets the novel’s references and details speak for themselves, trusting that his readers will appreciate the rich sense of place, whether or not they follow all of its nuances and inner workings. Consider the following description of the cabaret in which Outhman first meets Farah: “A group of cheikhat were singing songs while they danced, clapped, smoked, drank, and shook their fat bellies like bears, all to the drunks’ delight.” One does not need to be familiar with the professional women folk singers known as cheikhat to envision the lively scene or to appreciate Elinson’s rendering of Fadel’s muscular prose, which is light on adjectives and strong on active verbs.

Elinson’s choices give life to the novel and recreate Fadel’s loose and wise-cracking style and his occasionally wicked sense of humor. An illustrative example comes in the chapter narrated by Outhman’s neighbor Kenza, who works as a prostitute in order to raise money to support her son’s dream of immigrating to Spain. In the following passage, Kenza complains about her lover, who is in prison:

Even while he’s in prison there’s this idiot woman who provides for him, borrowing money and drowning in debt so he’ll lack for nothing. And one month before getting out of prison he has the nerve to say that I’d written him off. Great. I swear this New Year’s Eve I’ll sleep with ten men in one night. Just so he knows what sort of pen women use when they’re intent on writing someone off once and for all.

Here, Elinson makes effective use of contractions (“he’s in prison,” “I’d written,” etc.) to recreate the orality of Kenza’s internal monologue. With the interjection “Great,” Elinson evokes the rhythm of informal speech and also captures the meaning and tone of the Moroccan colloquial term mezyān (“Great,” delivered here in sarcasm). The pièce de résistance is the final sentence, in which Elinson finds an idiomatic English equivalent for the Moroccan phrase, “I mopped the world with him” (roughly meaning “I wrote him off”). By substituting a pen for the “mop” of the original Arabic phrase, Elinson builds on the English idiom “I’d written him off” and playfully adds a phallic connotation to it.

In conclusion, Elinson’s masterful translation brings to life an astonishing Moroccan novel about love, betrayal, frustrated dreams, emigration, government corruption, and the bonds that connect us to our neighbors, our cities, and the animals and inanimate objects that surround us. This work will, of course, be of interest to readers who are already engaged with Moroccan and North African literature, but it would be a shame if such a beautiful and poignant work only circulated among specialists. If you are looking for an introduction to contemporary Moroccan culture or even, I dare say, to contemporary Arabic literature, then I can think of no better starting place than Elinson’s translation of Youssef Fadel’s A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me.

Eric Calderwood is an Associate Professor in the Program of Comparative and World Literature at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of Colonial al-Andalus: Spain and the Making of Modern Moroccan Culture (Harvard University Press, 2018). In addition to his scholarly publications, he has contributed essays and commentary to such venues as NPR, the BBC, Foreign Policy, and McSweeney’s Quarterly.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: