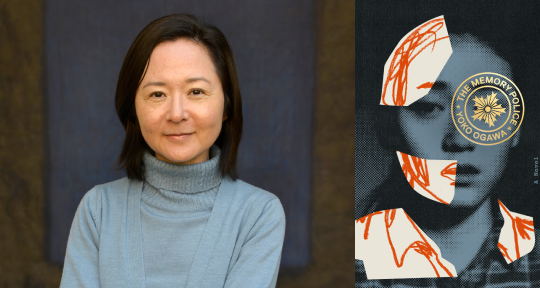

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa, translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder, Pantheon, 2019

It is easy to read Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police as a political allegory, along the lines of Milan Kundera’s oft-quoted proclamation in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting: “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Upon The Memory Police’s release in English this summer, publishing presses label the novel “Orwellian;” critics have similarly gravitated toward the timely themes of state surveillance and totalitarianism that form the novel’s backdrop, to which I relate in some way.

At the time of writing this essay, Hong Kong, the city where I was born, has been entrenched in protest for three months against the institutional violence committed by the government and the police force. With a crowdfunded campaign to place protest ads on international newspapers, a post on the August 19, 2019 edition of The New York Times asked readers to “[b]ear witness to Hongkongers’ fight for freedom. Tell our story—especially if we can no longer do it ourselves.” A month after, when two shafts of light went up in New York City to commemorate the eighteenth anniversary of 9/11, news headlines and Twitter posts abounded with the slogan “Never Forget,” used year after year to show the resilience of memory against trauma. Never have we been more well-equipped to record and share our experiences, but we are also more afraid than ever of not retaining control over our narratives, or of going unheard amidst the overflow of calamities documented around the world.

It might be useful to contextualize, however, that while The Memory Police is recently available in English—courtesy of the translation of Stephen Snyder, who has translated many of Ogawa’s other works—it was published in Japan twenty-five years ago. 1994 was a time when the world was just starting to mold itself into a semblance of what it is now: it is the year when the Internet went live, when Yahoo and Amazon, for better or for worse, were founded, and when Nelson Mandela won the first democratic election in South Africa. Unlike George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, which more violently demonstrates state power by means of espionage and torture, The Memory Police tells of characters genetically wired to forget things over time and the quiet ways by which they deal with its inevitability. More than political disaster, The Memory Police seems to challenge the very nature of memories as unfailing protectors of the past. Memories are easily lost and altered over time; their instability is what causes one’s sense of self to be equally precarious.

Little is known about the Memory Police on Ogawa’s unnamed island (by the time the story begins, maps have long since disappeared). Identified by their “dark green uniforms, with heavy belts and black boots,” the Memory Police operate “efficiently, thoroughly, systematically, and without any trace of emotion” for their sole inexplicable mission to see things disappear. While there are different ranks among officers, there appears to be no higher regime, no ulterior motive to consolidate power, only the intolerance of any delay in the process of forgetting. Whenever a disappearance occurs, it is not only the existence of the object or creature, but also the associated memories and emotions that get erased, as the narrator states:

Then I spotted a small brown creature flying high up in the sky. It was plump, with what appeared to be a tuft of white feathers at its breast. I had just begun to wonder whether it was one of the creatures I had seen with my father when I realized that everything I knew about them had disappeared from inside me: my memories of them, my feelings about them, the very meaning of the word ‘bird’—everything.

Memory has also featured as a theme in Ogawa’s other works. The Housekeeper and the Professor, one of her novels, is about a mathematician who can only hold memories for up to eighty minutes after a traffic accident. While the mathematician’s ailment is tragic but constant, memory loss in The Memory Police knows no bounds. The things people forget are numerous and grow increasingly absurd: from ribbons, birds, roses, and novels to people’s limbs, and at last their entire bodies.

Characteristic of Ogawa’s writing, the narrator and the characters in The Memory Police remain largely anonymous. One day, when meeting her editor, R, to discuss the manuscript of her novel, she discovers that he belongs to the persecuted minority whose genetic makeup causes them to retain their memories—just as her mother did, who was eventually taken away and killed. Determined to save him, the narrator enlists the help of her former nurse’s husband, an old man, and builds a secret room in her house, where R would stay. Over time, on R’s request to keep items that have been forgotten and are supposed to be destroyed, the secret room becomes a treasure trove of banned but endearing memorabilia: ferry tickets, harmonicas, ramune candy.

The secret room in fact receives more emphasis in The Memory Police’s original title, Hisoyaka na Kessho (密やかな結晶), which can be roughly translated to “secret crystallizations.” In an interview, Ogawa speaks about getting inspiration from Anne Frank’s experience for the secret room, which resembles the Dutch annex where the Frank family hid, and accords the start of her writing career to her own diary. “I read The Diary of Anne Frank when I was fourteen and realized that writing was a way for human beings to free themselves,” she said. “I gradually realized that storytelling begins in the very act of putting memories into words.”

Through the perspective of a novelist, The Memory Police illustrates the fear of being eroded until the self becomes “a hollow heart full of holes,” and writing as a medium of expression that, though unable to counteract that loss, nevertheless allows one to tell their tales. Living in trepidation of the next disappearance, the narrator works on her latest manuscript about a typist who has lost her voice and can only express herself with a typewriter. Sectioned between chapters of the book, this story-within-a-story explores the typist’s relationship with her teacher, which becomes increasingly manipulative and ends in the typist’s incarceration in a clock tower, surrounded by dysfunctional typewriters. Losing her ability to put thoughts into words, the typist slowly withers away and her will ceases to exist. Before her demise, she expresses a surprising sense of calm:

I close my eyes, realizing that the end is coming soon… But I suppose there’s no need to worry. It must feel much like a typewriter key falling back into place after rising for a moment to strike the page.

For a typist to compare her existence to a part of the machinery she orchestrates is a most helpless fate. Eventually, novels disappear from the island, and citizens set their books and the public library on fire. Like the typist, the narrator loses her mode of expression. However, unlike her character, who forfeits her chance to escape from the clock tower for fear of not adapting to the outside world after a long imprisonment, the narrator attempts to salvage what remains of her craft with R’s encouragement. Over a process of what may be described as a rather fitting portrayal of writer’s block, the narrator picks up her pen again, initially by staring at blank pieces of paper, then by copying characters. After some time, she reaches a point where her statements become poetic:

I soaked my feet in the water [ . . . ]

Not a speck of dust floated on the water.

I looked out on the grassy meadow.

When the wind blew, it made patterns in the grass.

Patterns like those in cheese nibbled by mice.

Although the narrator fails to find “the sense of a story” in her string of words, the imagery of translucence and erosion reflects the state of her existence of being ephemeral and emptied by forgetfulness. When the narrator vanishes, body part by body part until she herself disappears, she leaves her manuscript with R, which is to say she leaves her soul with him, along with the secret room. What, after all, are words to a writer but crystallizations of their being?

Turning to Kundera once more, as dystopian as the setting of The Memory Police seems to be, forgetfulness is intrinsic to the present moment. In Ignorance, Kundera states:

For after all, what can memory actually do, the poor thing? It is only capable of retaining a paltry little scrap of the past, and no one knows why just this scrap and not some other, since in each of us the choice occurs mysteriously, outside our will or interests. We don’t understand a thing about human life if we persist in avoiding the most obvious fact: that a reality no longer is what it was when it was; it cannot be reconstructed.

Scrappy as memory may be, and although reality cannot be reconstructed as it was, Ogawa emphasizes the importance of bearing witness to the past all the same. At the end of the novel, the hidden room is like a museum, filled with “secret crystallizations” that testify to people’s lives and ordinary moments. Like the narrator’s mother who once cherished a ferry ticket that no longer has any use, to treat the past with care is to show an appreciation for humanity and the values that were upheld. In the case of the ferry ticket, to the mother, it symbolizes freedom and hope for a better world beyond the island, a sentiment passed to the narrator as she tries to save the life of someone who will remember, at all costs.

Jacqueline Leung works in the arts and is an independent writer, translator, and editor. She is the Editor-at-Large for Hong Kong at Asymptote and a graduate of University College London and the University of Hong Kong in literary studies.

*****

Read more about Japanese literature on the Asymptote blog: