Room in Rome, by Jorge Eduardo Eielson, translated from the Spanish by David Shook, Cardboard House Press, 2019

Knots

That are not knots

And knots that are only

Knots

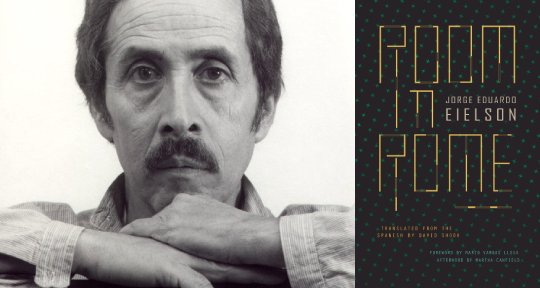

- Peruvian poet Jorge Eduardo Eielson once said of César Vallejo: “There is no superfluousness in Vallejo’s poetry, just as there isn’t any in Christian mysticism, although for opposite reasons”. This reason, according to Eielson, is that Vallejo’s poetry, as opposed to Christian mysticism that supposes a martyrdom of the body, is “a descent of the body—fleshly and social—into hell, that supposes another martyrdom, that of the soul.”

- Eielson writes the fleshly and social descent of the body into the Eternal City. Just looking at the title of the opening poem confirms Eielson’s commitment to the body: “Blasphemous Elegy for Those Who Live in the Neighborhood of San Pedro and Have Nothing to Eat.” Room in Rome was written in 1952, shortly after he had left Peru for Italy, where he would settle until his death in 2006. Vallejo, his hero, would also leave Peru for France. Despite this, Eielson’s book was widely available until 1977. During this period, he produced the novel El cuerpo de Gulia-no (The Body of Gulia-no). Again, its title suggests a rigorous investigation of the body and its descent into the worldly. Eielson would write, in 1955, Noche oscura del cuerpo (The Dark Night of the Body)—a shout-out to the Christian mystic St. John of the Cross.)

- “i have turned / my patience / into water / my solitude / into bread”

“here i am headless and shoeless”

“our father who art in the water”

“love will be reborn/ between my parched lips”

- The epigraph to Room in Rome is a line taken from Virgil’s Eclogue I. Meliboeus asks Tityrus: Et quae tanta fuit Romam tibi causa videndi? And what so made you want to visit Rome? And Tityrus answers: Libertas, freedom. I would ask Eielson what martyrdom made him want to go to Rome, the city that he kisses day and night. Perhaps his answer would have been freedom, too.

- Eielson was not only a poet; he was also a remarkable visual and performance artist. One cannot fully appreciate his written dimension without his visual and conceptual work. Eielson was known especially for his quipus—talking knots in Quechua—which were devices used by the Inca people to collect data and keep records. He started producing quipus (knotted canvases and twisted textiles) in 1963, which were exposed in the Venice Biennale, and continued to develop a distinct visual (and verbal) language of knots that sing, rather than talk.

- The language of Room in Rome is close to the knots of his quipus; each line is charged with tension and torsion. In “Valle Giuglia”, dedicated to Giuseppe Ungaretti, he writes:

where does the ma

n want to go with his cane that

breaks always bre

aks on turning the cor

ner

lead limbs before stairs

that rise daily

from so fragile an egg

and return to the egg

so fragile

The verbs in this fragment—to go, to break, to turn, to rise—are his violent and uncertain wanderings through the streets of Rome and many of the poem titles are names of streets. In “Via della Croce”—a lively street close to the legendary Spanish Steps—the knotting appears: “I have the sensation / of falling into an abyss / tied to my clothing / and to my chair.” The white pages are treated like canvas, and the lines as singing knots. However, like his knots, Room in Rome has poems that are not poems (they are knots) and poems that are only poems.

- Alejandro Tarrab, in an essay on Eielson, writes: “Knots, however intricate, must never be cut; there’s what happened to Alexander the Great with the Gordian Knot.” In the legend, Alexander tried to undo an intricate knot of cornel bark that tied an ox-cart to a post. Some versions have it that Alexander drew a sword and cut it; others say he successfully untied it. The Macedonian king went on to conquer the Persian Empire, fulfilling the oracle’s prophecy. Vargas Llosa, in his foreword to this translation, writes: “Eielson always kept something secret, an intimacy he preserved even beyond the reach of his closest friends.” If the knot is cut the song goes mute, the cipher of the oracle is destroyed, the secret of Jorge Eduardo Eielson is lost.

- I cry with the opening verses of “Obligatory Cry (In front of a Fountain in Rome)”:

there are things i don’t comprehend

except when crying

river of blood by the way

but in his hands a glass of water

and between his eyes the atrocious sound

of broken glass

Maybe you should cry, too.

- In the English-speaking world, Eielson’s textile art might be even more known than his textual art, but I believe David Shook has done a remarkable job in conveying Eielson’s earthy, precarious tone, making him available to the wider audience the poems deserve. There is a poem magically titled “Alongside the Tiber, Putrefaction Twinkles Gloriously”,—Shook has effectively captured that twinkling. Eielson has other important works that I hope become available in the future, and Shook is certainly up to the task.

- César Vallejo is the greatest Peruvian poet (I think he is the greatest Latin American poet) but Peruvian literature (in Spanish and Quechua) is rich and diverse, and authors such as José María Arguedas (he was Eielson’s high school teacher,) Magda Portal, Gamaliel Churata (El Pez de Oro is truly a wonder, think Jean Toomer’s Cane), Rodolfo Hinostroza, siblings Nicomedes and Victoria Santa Cruz, and Blanca Varela, are yet to be properly translated.

Sergio Sarano is Spanish Social Media Manager at Asymptote and Editor-in-Chief at Meldadora. His translation of Testimony by Charles Reznikoff is forthcoming from Matadero Editorial in 2020. He lives in Monterrey with his wife.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: