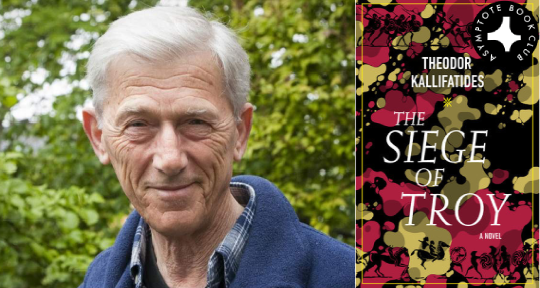

Contemporary writers have continually found original ways to tell enduring stories, as demonstrated masterfully in our September Book Club selection, The Siege of Troy by Theodor Kallifatides. By weaving the retelling of a classic myth with a World War II-era bildungsroman, this stirring novel simultaneously enlivens The Iliad while delivering a potent and poetic demonstration of war’s senselessness. Psychologically probing and structurally unique, The Siege of Troy is a thoroughly modern work that proves why we return again and again to timeless themes—there is always something new to be found there.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page.

The Siege of Troy by Theodor Kallifatides, translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, Other Press, 2019

No matter how many stories we’ve heard about love, war, and growing up, they never fail to reach our hearts in the specificity of our own place and moment. This is the simple, poignant premise of Theodor Kallifatides’s The Siege of Troy, translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, which sets an adolescent boy’s coming-of-age story against a selective retelling of The Iliad.

A Greek immigrant to Sweden, Kallifatides grew up during the German occupation of Greece, and his nameless protagonist emerges sweetly and painfully into his early manhood under the same conditions. The war is nearing its end; though both the occupiers and the occupied are exhausted, tensions continue to surge and survival is far from guaranteed. During regular air raids, the protagonist’s teacher recites The Iliad from memory to her class while they all take shelter in a cave.

Under the weight of war, adulthood genders its responsibilities in a way that the novel interrogates and criticizes. Men fight and defend according to principles that they haven’t determined or agreed to. Women soothe, mourn, and maintain homes for the men to come back to. The protagonist and his best friend Dimitra move between home and school trying to come to terms with the gap between their sense of self and the expectations placed on them, and the recitation of the Trojan War contains parallels that trigger reflection. After a particularly brutal part, the teacher and Dimitra comment: “‘A woman’s body is the field of conflict where men crush one another’s pride and honor.’ ‘I am fourteen years old, and my body is not a field of conflict. My body is me.’ Miss looked at Dimitra in surprise. ‘I hope you never forget that,’ she said.'”

Besides responsibility, love is the other inescapable feature of adulthood. The protagonist lives at the mercy of his love for his beautiful, mysterious teacher: “My only consolation was Miss. I never tired of gazing at her. She was small, dark, with burning eyes and beautiful hands, which she liked to move often. Officially we called her Miss, unofficially the Witch, because she could get the village’s bad-tempered, cowering dogs to stop barking. Otherwise they would even bark at their own shadow.” Meanwhile, Dimitra suffers from her own unrequited love for him. Arguably the more afflicted, she has to witness his infatuation while misidentifying with the female characters in The Iliad and lacking a truly successful female role model. Though problematically so, love is portrayed as a motivational force behind the impulse to survive.

The recitation of The Iliad occupies at least half of the novel, and this sneaky act of double translation serves a number of purposes. For one thing, it’s simply a compelling story that fits well with the central plot. For another, it offers a lens through which the characters process the traumas of life, love, and war. Finally, it makes this novel the site for a meeting between the ancient past and the eternal reader through the medium of narrative. Miss hints at this universality as she closes her recitation: ‘“He [Homer] wanted to talk about one thing and one thing only: the fact that war is a source of tears, and that there can be no victors.”’

Kallifatides has a stark, sensitive writing style that, in its simplicity, reveals a sense of reverence for his subjects; he creates multidimensionality subtly, through juxtaposition, hints, and suggestions. The drama of survival is muted by the banality of existence. . . and the mundane is simultaneously inflamed by its own precariousness. “We were young and powerless,” the protagonist tells us, “but Dimitra had discovered irony. The fact that life smiles at us with tears in its eyes.”

Lindsay Semel is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote. She holds a BA in Comparative Literature and works as a freelance editor from her home on a farm in Northern Portugal.

*****

Read about previous Book Club selections on the Asymptote blog: