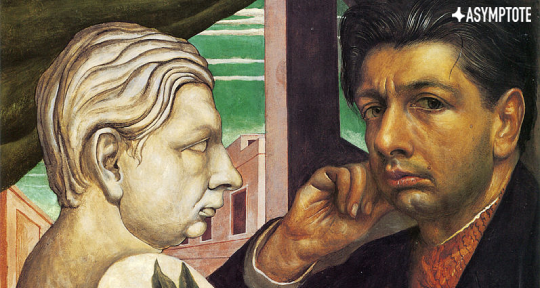

Ut pictura poesis. The language of painters has long been a source of inspiration for poets, and a sense of poetics has equally been an irreplaceable element in painting. In this evocative, sensual essay on the iconic painter and poet Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), Stefania Heim illustrates the various intersections between literature and visuality, between translation into text and translation into images, and between life and the page. This piece has been adapted from the original introduction of Geometry of Shadows, the first comprehensive and bilingual collection of de Chirico’s Italian poetry and translated into English by Heim, which will be published by A Public Space Books in October 2019.

Sun-scorched piazza, marble torso, rubber glove, arched arcade tossing shadows, smoke puffing from a background train: the landscapes of Giorgio de Chirico’s imagination have become iconic. It is a kind of magic to imprint the scenes created by your yearning onto the malleable backdrop of so many minds.

The uncanny emotive power of de Chirico’s visual compositions has gotten him called a poet, even a great poet. “He could condense voluminous feeling through metaphor and association,” writes art critic Robert Hughes about the painter’s canvases, marveling that, “[o]ne can try to dissect these magical nodes of experience, yet not find what makes them cohere.” Metaphor, juxtaposition, unsettling connections, meaning evoked in the missing connective tissue between somehow familiar objects—these are a poet’s tools. De Chirico cultivated this association. He addresses the two “goddesses:” “true Poetry” and “true Painting.” With allusion, symbols, and mythmaking, he connects his work to the great striving of the ages.

The idea of the poet crops up again and again in de Chirico’s painting titles: “The Uncertainty of the Poet,” “Delights of the Poet,” “The Nostalgia of the Poet.” In every case the poet appears as a vessel for feeling’s vicissitudes and registration. Two paintings are purportedly portraits of de Chirico’s friend and early supporter, Guillaume Apollinaire, but for the most part the perspective of these canvases zooms out. If a represented figure, the poet is a mannequin, a bust, or a tiny, silhouetted shape walking across the immense still heat of the frame. More often, I think “poet,” for de Chirico, refers to the mind that views and composes.

De Chirico didn’t only paint about poets; he risked the title for himself. A painter obsessed with materials—he wrote tracts on how to prepare a properly viscous canvas binder (the basis of all good painting, he cautioned, is the priming)—,he manipulated language too, with palpable attention to technical properties and textures. In de Chirico’s overlapping efforts, you can see his particular attention to what illuminations each set of tools might yield from the scenes that haunted him: iron artichokes, statues on low pedestals, an avenue shaded by pepper trees. He continually put the pieces together, looking at them through different arts.

—

Giorgio De Chirico was born in Volos, Greece, on July 10, 1888, the middle child of an Istanbul-born, railway engineer father of Sicilian descent and a mother of Genovese origin. His sister and father both died during those early years in Greece and he moved to Germany, then back to Italy with his mother and younger brother, the well-known writer, composer, and painter Alberto Savinio. Over the course of his life, de Chirico would live in Munich, Paris, Ferrara, Florence, Milan, New York, and Rome, where he finally settled and lived from the mid-1940s until his death in 1978. From these locations he participated, if sometimes unwillingly, in some of the most important art movements of his day—surrealism, dadaism, his own metaphysical art—and developed often-contentious relationships with the era’s most famous artists and writers. De Chirico’s Memoirs contain meticulous (if petulant and one-sided) delineations of his many perceived slights and parries in his moment’s effort to imagine the artist’s work—what art might be; how it should continue, break with, or respond to the ideas that came before.

De Chirico wrote throughout his life across a range of forms, going back and forth between French and Italian, sometimes intermixing Latin and English and imperfect Spanish. Often his writings were overtly polemical: essays on art, artists, and philosophy, memoirs, and autobiographical sketches. His French novel, Hebdomeros, was declared by John Ashbery to be the finest example of surrealist literature, and his French poems have been translated by renowned artists, Ashbery and Louise Bourgeois among them. Still, de Chirico’s writings are often treated like an apparatus to support the study of his much more well-known visual art. His Italian poems have not yet been recognized. Geometry of Shadows, collecting all of de Chirico’s known Italian-language poems, posits de Chirico not as a painter who happened to write, but as a poet.

The first poems collected in the book are from the period between 1916 and 1918 when de Chirico and Savinio came back to Italy from Paris, where de Chirico had been celebrating his first successes as a painter, having held shows at the Salon d’automne and the Salon des indépendants, which earned him the notice of Apollinaire and Picasso. War had broken out (“friends and acquaintances would disappear from Paris one after another, swallowed up in the war”) and the brothers returned in order to report for military duty. De Chirico describes this decision as having less to do with politics or the call of duty and more with their shared feeling of natal alienation. Enlisting, as de Chirico tells it, was an attempt to finally and officially “belong to one country.” This moment highlights de Chirico’s anxiety and conscious attempt at self-fashioning rooted in heritage and language. Many people, he asserts in his memoir, “feel that kind of modesty and shame due to being born in one country while possessing the nationality of another,” continuing: “even I and my brother had it and at that time we naively thought that in presenting ourselves for call-up, and doing our duty, as they say, we would change something.”

It’s hard to know what de Chirico thought would change, precisely, or how it didn’t. But de Chirico’s return to Italy did occasion an outpouring of creative work. In a 1919 essay, de Chirico links—in that grand, essentializing language he sometimes gives his prose over to—his motherland and his creative vision: the metaphysical art that emerged in 1910 in Florence and then developed in Paris and in these fertile Ferrara years. He writes, “From a geographic point of view, it was inevitable that the first conscious manifestation of great metaphysical painting should arise in Italy. It couldn’t have happened in France.” The French, he explains, had too much cultivation and facile talent, the Greeks too much artistic and natural beauty. “Our land” (he writes with all the conviction of that first-person plural), however, land of “inveterate gaucherie” and “chronic sadness,” is perfectly calibrated to nurture the “prophetic spirit.” For de Chirico, Italy and the metaphysical were inextricably, if somewhat painfully, bound. It was on desk duty during the war that de Chirico wrote his first Italian poems: strange, haunting, roving pieces, unsettled in either time or place—“My room is a beautiful vessel”; “My easel is a mast without its sail.”

The last section of poems in this book date from what is now known as de Chirico’s “neometaphysical” period, in which he revisited themes, scenes, images, and sometimes compositions from his earlier work. De Chirico’s practice (which began as early as the 1930s) of returning to earlier pieces and concepts has sometimes been seen as a problematic aspect of his career: “copies and ‘later’ versions—a euphemism for self-forgeries—are everywhere,” complains Hughes. For the art world, with significant money at stake in the constitution of its markets, de Chirico’s play with dates and copies could, of course, feel like a cynical maneuver. Outside of the anxiety of valuation, though, audiences have also struggled with how to understand these practices. Does de Chirico’s return to earlier ideas suggest the artist’s mania for self-improvement, also evidenced in his “Morning Prayer of the Perfect Painter”: “make it so that my craft as a painter / Is always further perfected”? Does it belie his overweening preoccupation with ideal forms, which so alienated his former friends, the surrealists? Or can these practices that were once, as Gavin Parkinson describes, “inexplicable and ridiculed,” now be celebrated for their avant-garde play with “irony, bad taste, camp, kitsch, appropriation, pastiche, parody, and plagiarism”?

Almost all of the poems in the final section—whose Italian iterations were penned or spoken in the 1970s—had earlier lives in French. These poems are thus reimaginings, revisions, translations, elaborations, and truncations. As one more instance of de Chirico’s “eternal return to himself,” they are, to my mind, the apotheosis of the metaphysical exercise as he describes it in his memoir: “The scene itself would not have changed; it is I who would be seeing it from a different angle.”

Line lengths and word order shift between the different iterations of the poems, similes are added, what was unclenched is maybe clenched, the point of view is refocused, a fragment is severed from what was an earlier whole. But, more than anything, the new angle of vision de Chirico brings to these older, haunting scenes and compositions comes through the window of language. He wrote these Italian poems when he had been living in Rome steadily for thirty years. Perhaps that something he had wished for—a way of seeing and, in turn, being seen—had finally changed?

Many other poets have left complex archives of versions, scraps, and iterations, upending any fixed location of, or approach to, their work—Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Fernando Pessoa spring readily to mind. Other poets have written the “same” piece across the different languages in which they think and dream and live. There are Juan Felipe Herrera’s facing pages in his own Spanish and his own English, Mónica de la Torre’s experiments in self-translation. (“Only by rubbing one language against another might we perceive a differential that charges words with near animistic power,” she writes.) It feels illuminating to encounter de Chirico’s play in language beside this kind of writing, reading, and translating—writing that is at once a reading and a translating. Despite acropolises and marble statues that seem to embody endurance and the ideal, vision and meaning are not static or still in these works. The statues walk off their low pedestals and into the crowd. Pallas Athena awakens, leaning upon her staff. The metaphysical idea, after all, is that memory and history are always erupting into the present. Any present we make must be open to their interventions.

—

Culling and compiling the texts that would become Geometry of Shadows, I thought of translator and theorist Karen Emmerich’s argument that every translation instantiates “an original” where no such stable thing existed to begin with. “So-called originals,” she writes, “are not given but made, and translators are often party to the making.” Her insights felt urgently true in the case of de Chirico’s writings with their tricky dating and paper trails, their self-references, their edits and shifts, their self-quotation and repetition.

I started working from issue number 7/8 of Metafisica, the journal of the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, which presents all of his known poetry and prose poetry: his versions in Italian and French, his notes, his cross-outs, pulled from manuscripts as well as myriad publications that had appeared both during the artist’s life and posthumously. I began by translating the early, free standing Italian metaphysical poems and prose poems. Though immensely difficult in terms of language, imagery, and syntax—perhaps because they were difficult in these quintessentially poetic ways—the poems were immediately legible as early twentieth century literary experiments. And, indeed, they had come into the world precisely as such: published in the European magazines where modernist visions and ideologies of contemporary art making were being articulated and argued over. These pieces are in direct conversation with other writers, in their references, dedications, and forms.

De Chirico’s exploration of language’s material textures can be felt within this body of these poems. Some have lines and phrases in other languages, which I have kept in the English translation. Others have elements that push against the boundaries of Italian. Sometimes a single letter locates a word at the intersection between tongues: for example, “immurabili,” a word so close to “immutabile” (unchanging), but with an “r” that constructs mura, walls, within it. I added that “r” into the English, as well. Some words put up greater resistance. What are the falling “iguerros” in “Canzone”? Are they the large, spherical, gourd-like fruits of the Calabash tree (Crescentia cujete)? Or are they the common fig, la higuera? With a word, de Chirico made languages collide, and with them, landscapes, worlds. In translation, I have tried to honor these textures, tried to stay hovering just a bit between.

A landscape with contradictory vanishing points, sentences that pick up speed wending precariously across lines: de Chirico’s poems manipulate grammar as his paintings manipulate space. In Italian, word endings can provide an orienting principle—connecting a verb to its agent, an adjective to a noun, even across a great distance. De Chirico’s poems often stretch these connections to their breaking point. English is more beholden to word order and its syntactical connections snap quickly. Translating, I played with how to maintain de Chirico’s energy and enigma without introducing mere confusion. In both form and content de Chirico’s poems ask: What connects us to the things we remember? To the spaces we inhabit? How are landscape and memory connected to each other? How strong are those connections? Can anyone else see them? The word for room in Italian is “stanza,” and it seems inevitable that the stanzas of poems would house de Chirico’s “metaphysical interiors,” becoming a container for his wild and domestic musings across space and time.

The most complicated choices came as I moved from de Chirico’s middle period to the last poems, his versions from the 1970s. In Metafisica, these mostly short, late pieces are presented among and sharing pages with their notes and multi-lingual variations. Getting a hold of two essential objects clarified my sense of these poems as poems on their own terms and turned up new pieces that had not been in the foundation’s collection.

The first object, the ephemeral art volume Tic di Guelfo published by collector Guelfo Bianchini, is filled with de Chirico’s poems both typed and written in his hand, alongside testaments of friendship, photographs, and facsimiles of artworks both major and minor by de Chirico, Bianchini, Saviano, Hans Arp, Man Ray, Joan Miró, and others. It is a kind of intimate museum of artistic experimentation, out of which these late Italian poems shine and resonate with each other.

The second object is the 1976 RAI television segment, “The unpublished poems of Giorgio de Chirico,” one in a series of short art documentaries directed by Franco Simongini. A camera tracking de Chirico as he walks through his Rome apartment, Simongini opens the twenty-minute segment with some words about de Chirico the poet: calling him “lyrical and meditative” as well as “paradoxical, quick-witted, rich in humor and irony, even regarding himself.” In the film, Simongini, peppering de Chirico with questions both deep and banal, keeps handing him sheets of paper with his poems to read for the camera—all of them these late, Italian-language lyrics. The eighty-eight year-old artist protests, “You are making me work too hard.” “You put too much of yourself in your poems,” Simongini suggests, feeling for an interpretive hook. “I suffer,” de Chirico deadpans. It is the quickest of volleys—the poet’s hand moves to his heart, one mischievous light sparkling from an otherwise grave face. He reads the next poem.

Every translation, of course, is an argument about the how as well as the what of a text’s meaning: that light that escapes from behind the mask of gravity. I entered the world of de Chirico’s imagination attuned to particular objects and scenes, eager to render them. I was continually surprised by what I found there, both inside and outside of his geometric, refreshing shadows. I offer my translations as a metaphysical undertaking: one momentary angle of attention on this remarkable landscape.

Stefania Heim received a translation fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for her work on Giorgio de Chirico. Geometry of Shadows, her volume of translations of de Chirico’s Italian poems, will be published by A Public Space Books in October 2019. A founding editor of CIRCUMFERENCE: Poetry in Translation and a former poetry editor of Boston Review, Heim is the author of two collections of poems, HOUR BOOK, which was selected by Jennifer Moxley as winner of the Sawtooth Prize and published by Ahsahta Books in 2019, and A Table That Goes On for Miles (Switchback Books, 2014). She is an assistant professor of literature at Western Washington University.

*****

Read more essays on the Asymptote blog: