According to Sylvia Plath, August is an “odd and uneven time” so it’s all the more fitting that we’ve chosen Juan José Millás’ spectacularly surreal and cerebral novel, From the Shadows, as our Book Club selection this month. Millás is an author known for bringing existential thought into dreamlike spaces, and in this exemplifying work, the narrative carves a labyrinthine path through a mind withstanding both physical and mental confinements, and the language, rife with darkness and comedy, traces the fine walls of worlds both real and imagined with Kafkaesque soliloquy.

The Asymptote Book Club strives to bring the best translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. From as low as USD15 a book, sign up to receive next month’s book on our website; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page.

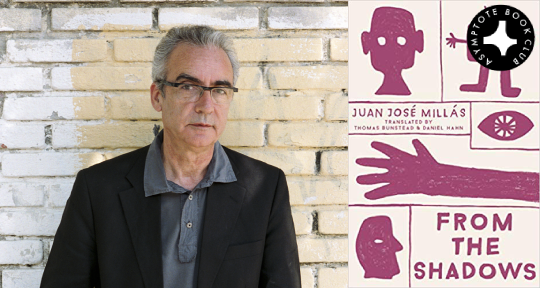

From the Shadows by Juan José Millás, translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead and Daniel Hahn, Bellevue Literary Press, 2019

“Every love story is a ghost story”: David Foster Wallace’s epigraph encapsulates the phantasmagoric search for love and acceptance in Juan José Millás’ From the Shadows, the author’s much-anticipated English debut. Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead and Daniel Hahn, From the Shadows follows the story of Damián Lobo, an unemployed maintenance worker, who, in a strange turn of events, hides himself inside an old wardrobe and gets transported to the home of a young family. Instead of escaping from his physical confinement, Damián inhabits the space behind the wardrobe and becomes the “Ghost Butler,” a spectral being who tends to chores around the house in the daytime when the family is out and slips back to his hiding place in the master’s bedroom at night.

With what appears to be an absurdist plot, Millás explores the psyche of an individual made redundant by society. In an age where things are replaced rather than repaired, Damián has spent the last two years of his job largely idle and alone in the basement of his company building, with only the internet, mice, and the gurgling sounds of pipes for company. Even in his family he feels like an outcast; he fantasizes about his Chinese sister who, in his mind, is more valuable to his parents because she was adopted, therefore embodying his parents’ charity, while he was the accidental child they had no intention of conceiving. Like “a moray eel hiding in a seabed crevice,” a comparison cited at various points throughout the text, Damián withdraws into the recesses of his mind and engages in imaginary and extensive TV interviews. Large parts of the novel are in the form of conversations despite Damián’s self-isolation, and it is through these interviews that Damián divulges the decisions and emotions he can never convey in real life, a confessional exercise that is at once cathartic and anxious. Pretending to be a celebrity on air, Damián revels in the gratifying reactions the audience has toward his humor, but also treads with caution in wording his responses, for, ultimately, his imaginary viewers are most eager for tragic and salacious content.

Millás’ prose switches between the physical world and the make-believe TV studio seamlessly, showing both dimensions to be concrete realities to Damián. It has been suggested that Damián’s mental conversations are symptomatic of dissociative order, a state of depersonalization and detachment from oneself, but what is interpreted as psychological deterioration is in fact a liberation of the mind from the capitalistic society that has failed him. As Damián adapts to his new lifestyle, he ponders on the time he has spent trapped in “the fictitious freedom of the outside world”; paradoxically, it is in the claustrophobic space of the wardrobe where he discovers a “new kind of liberty [marked] by great mental fluidity, his thoughts flowing where they would, as though just one more bodily secretion.”

However, even as Damián progresses toward a ghostly existence—his body turns increasingly ephemeral by ingesting less food and producing less waste, and his senses develop an “internal vision” that allows him to visualize the events happening in the house with just his hearing—the fact remains that his phantom existence is only real to those wanting to interpret reality via the lens of paranormal phenomena. It is therefore his fortune to find a sympathetic believer in Lucía, the woman of the house, who is unfulfilled in her marriage and takes Damián to be a benevolent spirit that has come with the wardrobe, a memento of her childhood. Their strange but reciprocal relationship casts Damián as a spectral guardian watching over Lucía and causes him to imagine his integration into the family:

He sometimes wondered how long the situation might last. He fantasized about it lasting forever. And about things progressing, too, in the sense of a day arriving when he would be able to step out of the wardrobe and move among them, while remaining invisible. They would all be in the kitchen, living room, hall, all four of them at the same time, but the other three would not see him.

Damián’s desire to belong, which ultimately leads to tremendous consequences for the family, is indicative of the ramifications of modern-day solitude From the Shadows seeks to portray. Like the existence of ghosts, simultaneously manifest and invisible, the novel articulates our contradictory impulses to withdraw and express ourselves, and the ease with which we descend from the ordinary to the perverse. It may be difficult to embrace Damián for his aberration, but Millás’ unflinching narration shows all the more our willingness to go to great lengths to salvage our significance in the world, however meagre and tenuous.

Jacqueline Leung works in the arts and is an independent writer, translator, and editor. She is the Editor-at-Large for Hong Kong at Asymptote and a graduate of University College London and the University of Hong Kong in literary studies.

*****

Read about previous Book Club selections on the Asymptote blog: