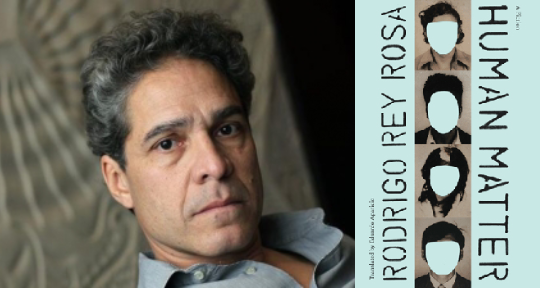

Human Matter: A Fiction by Rodrigo Rey Rosa, translated from the Spanish by Eduardo Aparicio, University of Texas Press, 2019

As noted over the years by scholars such as Arturo Arias, Central American cultural production remains largely at the margins of academic study. As Arias points out in Taking Their Word, because popular knowledge of the region is so sparse, and because geographic ignorance (particularly in the United States) is so widespread, Central American immigrants will often identify Mexico as their country of origin, both for reasons of Latinx solidarity, and to protect themselves from discrimination and prejudice. This erasure is not even a recent phenomenon: the protagonists of the 1983 film El Norte, the Guatemalan-Maya brother and sister Enrique and Rosa Xuncax, are told to tell people that they are from the heavily Indigenous state of Oaxaca, Mexico, to avoid being taken advantage of in both Mexico and the US. However, from the United Fruit Company in the early twentieth century to the practices of Canadian mining companies, and even US president Donald Trump’s facilitating, in the words of the Guatemalan-American author Francisco Goldman, “organized crime” in Guatemala’s 2019 presidential elections, global forces have always played, and continue to play, an outsized role in the region.

Despite its apparently marginal status, the region has made a number of enduring contributions to world literature. Foremost among them is one of the fathers of Latin American modernism, the Nicaraguan Rubén Darío, and the Guatemalan Nobel Laureate Miguel Ángel Asturias, not to mention one of the most important works of Indigenous literature in the Americas, the K’iche’ Maya Popol Wuj. Outside of these points of reference, however, much of the region’s vast, rich literature remains untranslated, which makes Eduardo Aparicio’s translation of Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s El material humano as Human Matter all the more important.

Rey Rosa, perhaps Guatemala’s most important living novelist, has had an eclectic literary trajectory. Having gone to New York in the early 1980s, he eventually became the protégé of the US-expatriate author Paul Bowles, spending a good deal of time with the author in his adopted home of Tangier, Morocco, and even becoming executor of Bowles’s literary estate upon the author’s death in 1999. Tellingly, one of Rey Rosa’s previously translated novels, the magnificent The African Shore, deals with the intersection of tourism, privilege, and migration in the border zone not between Guatemala and the US, or even between Guatemala and México, but between Morocco and Spain.

By comparison, Human Matter takes up the nameless protagonist’s exploration of Guatemala’s infamous National Police Archives. The actual archive is a largely unorganized mass of documents, discovered in 2005 in an abandoned munitions building, and contains papers going back to the nineteenth century, including countless files on people who were targeted by the Guatemalan state, disappeared, and/or were murdered during the country’s bloody civil war. With many of the perpetrators’ family members, such as Zury Ríos, the daughter of the ex-president Efraín Ríos Montt, still important political players, the archive and what it may or may not contain remains a potentially explosive topic within Guatemalan society. In a brief note at the beginning of Human Matter, the author himself takes pains to assert that the book in question, “Though it may not seem to be, though it may not want to seem to be, is a work of fiction.” Nonetheless, in a move in which fiction clearly holds a mirror to reality, when the protagonist is undertaking research into the Archive’s Identification Bureau, and into the mysterious character of its founder, Benedicto Tun, he is discouraged from moving forward: “For my own safety, and because some of the cases opened after 1970 could still be active or pending in court, [the head of the Archive Recovery Project] asked me not to consult any documents dated after that year.” As records from the Identification Bureau are literally unearthed and the slow march of the government’s documenting and, indeed, constructing of the category of “criminal” moves forward, the protagonist is denied access to the official archive. The novel continues unfolding episodically, day by day, across vignettes, such as conversations with the aforementioned Tun’s son, the protagonist’s recounting of his own mother’s kidnapping and release some six months later, his daughter’s teacher confessing that she thinks people are watching her, and a friend’s attempt to gain asylum out of the country. Past violence, whether that of Guatemala’s countless coups, the Spanish conquest, or Guatemala’s oppression of its Indigenous peoples, so infuses the present that historicity and documentation seem to be ever more pressing needs and yet ever more impossible as daily survival becomes the horizon of human existence, documented or not.

An exercise in the resilience of human memory, the novel integrates a broad swath of literary and global cultural touchstones that situate it as a novel that is simultaneously a great work of uniquely Guatemalan literature and a masterful piece of world literature. Moreover, despite its fictional status, moments such as the protagonist’s having dinner with Paul and Jane Bowles’s French translator are sly, metafictional nods to the fact that the world of the novel remains all too real. Aparicio’s meticulous translation is beautiful, inviting the reader into the text without shying away from asking them to engage Guatemalan reality on its own terms. On the very first page, for example, the Guatemalan Civil War is referred to as the “domestic war,” which I imagine as a translation of the oft-used phrase guerra interna. The use of the word “domestic,” with its connotations of home and family in English, imbues the conflict with precisely the intimacy that it still has for Guatemalans, conveying that unsettling reality to readers. For readers who are encountering Rey Rosa for the first time, or continuing their familiarity with the region, the book offers a tragic, uncomforting window into the long processes of death, war, and hopeful reconciliation that have haunted the Americas for over five hundred years.

Paul Worley is Associate Professor of Global Literature at Western Carolina University. He is the author of Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures (2013; oral performances recorded as part of this book project are available at tsikbalichmaya.org), and with Rita M. Palacios is co-author of Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (2019). He is a Fulbright Scholar, and 2018 winner of the Sturgis Leavitt Award from the Southeastern Council on Latin American Studies. In addition to his academic work, he has translated selected works by Indigenous authors such as Hubert Malina, Adriana López, and Ruperta Bautista, serves as editor-at-large for Mexico for Asymptote, and as poetry editor for the North Dakota Quarterly.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: