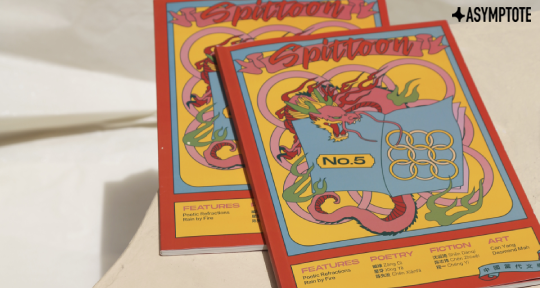

Spittoon is a literary and arts collective born in Beijing, China, with the aim of bringing together Chinese and foreign writers, artists, and creators. Consisting of monthly events, poetry-music intersections, and literary and artistic publications, Spittoon has set down roots in Beijing, Chengdu, and Gothenburg, Sweden. In June 2019, Spittoon Literary Magazine Issue 5, a bilingual publication that translates and publishes China’s best contemporary voices, was published. Xiao Yue Shan, Managing Editor of the magazine and Assistant Blog Editor at Asymptote, writes from Beijing about the days leading up to the launch.

Drivers here love talking politics, my aunt says to me after my hour-long ride into Xiaotangshan, the oddly idyllic suburban town in northwest Beijing. Really? I reply. They’ve been telling me the stories of their lives.

Beijing is brimming to burst with stories, occasionally startling, occasionally brilliant, told in voices bred by an immense variousness, from the sandy waters of the Yellow River to the steaming skies of Hunan, the stillness of Heilongjiang winters to glittering Kunming greens. It is a city that collects and bounds the language of its citizens, between circling highways and sky-bound apartments. So it is that one is never beyond the reach of a story, told as regularly as the hour tells the clock.

The literature of contemporary China is represented in the contours of Beijing—a place you must visit a great number of times, an ongoing landscape impossible to traverse by foot alone, wayward beginnings which speak nothing of ending. Any attempt to define it would be a disservice, as it openly resists definition; one is only able to catch at its hems, glancing, in search of openings that allow light to come in, any small light that would lend sense to the vastness. So it is with this knowledge that we, at Spittoon Literary Magazine, set out to compile a selection of China’s most engaging and original literatures, carving a door by which one can visit again and again. This publication is an entryway toward something lasting, a portrait of a national body that refuses to stay still. Within it, we celebrate the immense, wondrous heights of the Chinese language.

I have arrived in Beijing, leaving behind an atypically cold Tokyo June, to welcome Issue 5 into the world. After staring at the text wrapped up in the blue light of a computer screen for months, it is thrilling to think that deep in the city, there are stacks of copies, physical copies that have real weight, that can be passed from hand to hand and marked up inky and take up space on a shelf. Half-asleep, I look out from the window into the yard laden with fallen apricots and early-afternoon daze, and reread in my head the stories and poems I know now almost by heart, anticipating their weight.

表面上,愿意站多久都可以;

但实际上在一株盛开的山桃树下

一个人究竟能驻足多长时间

是早有规定的。It seems as though you could stay as long as you wish,

but how long you’re allowed to stand

under a blooming mountain peach tree

has long been a truth unspoken.反艳遇学入门 Gateway to the Art of Anti-Dalliance

臧棣 Zang Di, translated by Zuo Fei and Kassy Lee

The literature had arrived to us by a convoluted system of luck, series of hard-won personal connections, and intuition. From poets of significant renown to the young and prodigious, to fiction writers of surrealist, realist, and absurdist nature, Issue 5 seeks to represent, without any notion that in representation there could be finality. While writing the editor’s note, the first thought that came to my mind was distance. Distances measured and unable to be breached, distance we briefly have language for. Distance travelled in certain patterns from the minds of writers, words turning now towards us, distance translators seek to forget or commemorate. One must learn how to read again, not just again but better.

在晚上睡觉前祈祷下一个梦是全然的中文。只有在用中文做梦之后的清晨,她会显得迷蒙又愉快,她会说她昨天做了个好梦。

Before she went to bed she said a prayer that her dreams would be entirely in Chinese. It was only from Chinese dreams that she would wake up in the morning and announce, with a bleary feeling of contentment, that it had been a good night’s sleep.

中国特色的译文读者 A Reader of Translations (With Chinese Characteristics)

沈诞琦 Shen Danqi, translated by Dave Haysom

In Beijing, the concrete is gravity. Past gutters rainbow with oil and low summer branches whispering down the tired hutong walls, I arrive at a low door which seems to present a test of sorts, entwined with open-ended candy-coloured wires, framed by sunned stones. People are eating apples and sharpening knives and fixing broken bicycle bells. The driver asks me (Guangdong accent), this is it? He had been in the middle of talking about Pearl River. This is it. Behind the door are people whom I have worked alongside to bring Issue 5 into reality, and they are people who have previously only taken on the shapes of disarmingly green text boxes or crackling voices blurred at the edges. We meet in pages, then in life, and the feeling is simultaneously miraculous and anticlimactic—of course they were here the whole time, but how was I to know that?

In translation, the non-language is gravity. One meets the work with the intention of having to settle a debt, stemming from some innate sense that one must do “justice” to the original. Yet justice cannot be defined by the perfect transference of one language to the next, because one must not forget that language is the medium by which impressions arrive, all these senses outside the realm of language. So the piece already exists, but how is the piece yet to be written supposed to know that?

有时候,一些低语声不断地从那 无尽回环往复的螺旋通道中抵达他身体内部的那个深渊,然后从那里飞快地掉落下去,无始 无终。这是一种非常奇怪的感觉,这些由螺旋走廊构成的回环往复的世界,仿佛他自己就置 身于这个世界的里面,但他知道她是在外面。

Sometimes, some utterances reached down to him through the endlessly looping, spiral halls before plummeting straight down into the depths with no beginning or end. This looping world of spiral corridors, produced within him a strange feeling, as if while he was inside it, he knew she was outside of it.

在病房 In the Ward

程一 Cheng Yi, translated by Deva Eveland, Remington Gillis, and Yidan Liu

The story of Spittoon Collective (told by those before me) is that it started in these hutong bars crossed and glimmering, with understuffed couches and neglected twinkling lights and friends who wanted their language to create spaces one could go and return to. Yet the magazine has taken on the task of bringing a country to the table for a conversation. The individuals that make up Spittoon Collective are collected from around the globe in another instance of defying distance, yet we are all identically enamoured with the urgent and rogue nation of stories.

I have an emotional attachment to the Chinese language. It will always be that which gave me the names of colours, the wetness of water, the morning scent of my mother. So it is that Chinese literature in translation presents a particular difficulty in which I am relegated to saying: that just doesn’t feel right. Sometimes this can be a little better explained by the components of the character (there’s the radical of fire, so it feels like it should be a little more aggressive, more biting) or the resonance when said aloud (Beijingers tend to shrink that last word away and lilt it upward), but just as often, it comes down to something like—but the feeling. I am more likely to give up in an argument pertaining to the translation of a single word, out of fear of sounding like a petulant child. It is not a loss; in this process I have learned that every dialogue is one that opens up wider avenues, splintered here and there with one’s own history and attachments to language, towards the work at hand.

站在结构的空白处

听窗前孩子

读出你的诗足够。To stand in the empty structure

And listen to children by the window

Reading your poetry is enough.知不死记 Notes on Knowing Immortality

陈先发 Chen Xianfa, translated by Nell Greenhouse

We’ve got it pretty good, my uncle says, echoing the words of my father. You can’t even imagine how poor we were before. I look out the window as we speed through 5th Ring Road. I don’t know what everybody else is complaining about these days, but China is a good place to live, it has become really a great place to live.

The urgency I speak of in Chinese literature comes from not only the tumultuous and traumatic history of the country, but is also attributed to the fact that as the country grows in both wealth and in measurable satisfaction, its people are given more opportunities to consider their lives deeply. The literature of revolution and survival was potent and indispensable, but so is the work that arrives in seemingly quieter times, when writers are afforded the occasions to sit deeply with themselves. The contemporary writing of China is rich with curiosity, beatific with knowledge, chasmic with contemplation, and blazing with an immense and timeless need to tell its stories.

Of all that Spittoon Literary Magazine has accomplished in its young existence, Issue 5 marks another step forward in both breaching and honouring distance. All things forgotten and remembered are kept—in words, in voices, in this volume of literature created by one’s fellow travellers in language. The covers open to a rich spread of identities and crafts, linked by the nation known for its enormity. The light has been lit; we invite you to sit with us awhile.

All the pieces excerpted in this essay can be read in Spittoon Literary Magazine Issue 5.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and essayist born in China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, published in early 2019, was the winner of the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize. She currently works with Spittoon Literary Magazine, Tokyo Poetry Journal, and Asymptote.

*****

Read more essays on the Asymptote blog: