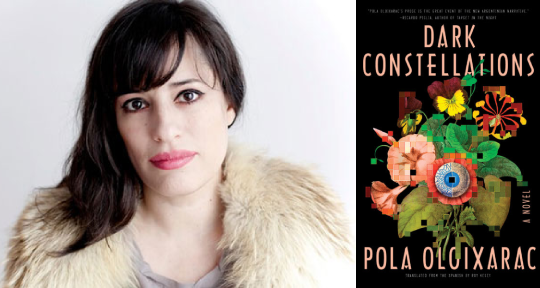

Dark Constellations by Pola Oloixarac, translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey, Soho Press, 2019

The Incas, according to Pola Oloixarac’s Dark Constellations, didn’t see the night sky as we do: instead of what we might call “connecting the dots,” they focused on the darkness between the stars, the shapes formed by negative space. If true—and it’s hard to know what, exactly, is true in Dark Constellations—it’s an intriguing image, one that informs our understanding of the novel’s structure as well as its content.

Dark Constellations, translated into English by Roy Kesey, is the second novel from Pola Oloixarac, one of Argentina’s rising literary stars (pun intended). Like her countrywoman Samanta Schweblin, whose story collection Mouthful of Birds has recently garnered considerable attention, Oloixarac tends to blur the line between science and the supernatural, taking a certain kind of pleasure in repeatedly throwing the reader off balance. Dark Constellations, however, has a much wider range than Schweblin’s stories, skillfully handling subjects as varied as botany, world history, and computer programming. The book’s publisher, Soho Press, calls Dark Constellations “ambitious,” and while I agree completely, I would argue that the novel’s ambition is its greatest weakness as well as one of its strengths.

Coming in at just 216 pages, Dark Constellations is divided into three main sections, each named for its central character. The book begins in 1882, when a group of European explorers, including the Darwin-like botanist Niklas Bruun, lands on a mysterious island somewhere off the coast of Africa. The expedition quickly devolves into chaos when the men get lost in a network of caves, stumble upon a group of natives, and are promptly incorporated into a set of unsettling sexual rites. For Niklas, this misadventure is just the beginning: he returns to Europe a celebrity and goes on to travel the world in search of botanical wonders. Much later in the book, we catch up with him in the Amazon.

Oloixarac’s keen eye for historical detail comes through most strongly in Niklas’ sections, which are interspersed with rambling journal entries and quirky but realistic details (one of Niklas’ contemporaries, for instance, has written a book with the wonderful title of “Orchidaceaen Dithyrambs”). Niklas’ encounters with native people, and particularly native women, clearly echo Columbus’ first letter about his arrival in the New World, one of the foundational texts of Latin American literature. By opening Dark Constellations with a scene of conquest, both colonial and sexual, Oloixarac situates her readers in a familiar literary tradition and primes them for two of the book’s main themes: gender dynamics and the exploration of uncharted territory.

These ideas are probed in greater depth in the second, and longest, section of Dark Constellations, which centers on a young man named Cassio. We are led to believe, at the end of the first section, that Cassio’s work on the dystopian-sounding “Project” is somehow connected to Niklas Bruun, but we don’t return to that link until much later. Instead, we’re transported to the 1980s, where we follow Cassio’s Argentine mother and Brazilian father as they meet, marry, and divorce. Baby Cassio returns with his mother to Argentina, where he grows into a lonely child, a computer-obsessed teen, and then a world-class adult hacker.

It’s at this point in Dark Constellations that the downside of the book’s ambition starts to become clear. Oloixarac writes with total authority on complex scientific concepts and excels at vividly capturing the mood of a particular time and place, but the intricacy of her world-building often comes at the expense of character development. The wide lens required to encompass multiple lifetimes and continents also has the effect of flattening characters out, preventing the reader from becoming fully invested in them. More than half of Dark Constellations is devoted to Cassio, but by the end of the section, he’s still unpleasant and off-putting; while there’s a case to be made for unlikeable protagonists, this one in particular has the effect of dampening the reader’s interest and enjoyment.

At least part of Cassio’s lack of appeal may stem from his attitudes towards women and the role they play—or don’t play—in his life. When I first picked up Dark Constellations, I assumed (perhaps wrongly) that because it was written by a young female author, it would be full of complex and compelling women. But midway through the book, I had encountered more descriptions of male genitalia (“meaty joystick” and “his pole in all its splendor” are particular standouts) than female characters worth mentioning. Sonia, Cassio’s mother, mostly disappears from the story once her son has reached adolescence; Melina, the receptionist at Cassio’s otherwise male office, has a brief sexual relationship with him. By the time I reached the end of the book, I had forgotten Melina’s name.

I was preoccupied by this conspicuous lack of female representation until I realized how purposeful it was. In its pigeonholing of women and off-putting descriptions of sex, Cassio’s story is meant to demonstrate how successfully Argentina’s machista culture—and its roots in the European culture of colonial explorers like Niklas Bruun—has minimized women. In placing Niklas and Cassio side by side, Oloixarac shows how little has changed in the hundred years that separate them: each of their cultures has managed to keep women off the front lines of exploration and technology. It’s no coincidence that Cassio’s mother, Sonia, is forced to become a housewife while her husband works at a high-level aeronautics institute in Brazil.

In its reversal of the gender dynamics mentioned above, the third and final section of Dark Constellations stands in stark contrast to the other two. Its title character, Piera, is a renowned biologist who has been hired to work on the Project, and when she first arrives, her new coworkers stare at her, confused: “the boys of the Project must think she’s on the administrative staff, here to look for something that’s gone missing.” Piera fits almost too perfectly into the “strong female character” mold that has been so noticeably absent from Dark Constellations up to this point—she is intelligent, competent, and courageous—but her inner life, like Cassio’s, leaves something to be desired. What Piera most resembles is the star of an action movie: while the reader is happy to follow her adventures, there’s very little about her that is memorable or unique. Even at the novel’s end, Piera retains a certain opacity. The idiosyncrasies and inner conflicts that keep characters alive for us long after we’ve finished a book are, in her case, mostly left out.

Interestingly, though, Piera’s seemingly straightforward role as a woman who has come to upend the patriarchal Project is complicated by two unusual authorial decisions. For one thing, both Cassio and Niklas’ narratives interrupt Piera’s section, a structural choice that, while necessary for plot purposes, is strikingly at odds with Piera’s apparent function as the book’s feminist champion. The other point worth mentioning is Cassio’s repeated comparison of Piera to Monica Lewinsky. It’s hard to know what to make of this image: is it a commentary on Cassio’s own unshakeable sexism, his inability to see women in any context other than the sexual? Alternatively, does it reflect the kind of rethinking of Lewinsky that has emerged from the #MeToo movement, a new narrative in which she emerges the victim of a gendered power imbalance? But since there’s very little of the victim in Piera, could it be an even more radical reframing of Lewinsky, one in which an underdog, an intern, has the power to nearly upend the world’s most powerful government?

This may be a question best left to the reader, as I don’t want to spoil Piera’s role in the (somewhat disjointed) conclusion of Dark Constellations. The problem, yet again, lies in the book’s ambition: keeping track of a relentless stream of characters, high-level scientific concepts, and the relationships between them proved nearly impossible, and I often found myself looping back to previous chapters to double-check names or reread dense technical passages. Niklas Bruun’s storyline, which I initially enjoyed, ventured much too far into the supernatural for my taste, and certain aspects of Cassio and Piera’s plot never fully became clear to me.

While the individual sections of Dark Constellations don’t necessarily come together to form a successful whole, the book is still an enjoyable and enlightening read; Cassio’s philosophizing about the role of technology in human life is particularly thought-provoking, and the lush descriptions of Niklas’ Amazonian expedition read beautifully in Roy Kesey’s translation. While the plotlines aren’t entirely resolved, there is no shortage of impressive passages in this novel, and readers are bound to close the book with an appreciation for Oloixarac’s erudition and skill.

And this brings me back to the image of negative space, the “dark constellations” that serve as an entryway for understanding the book as a whole. The characters and plot points can be imagined as stars in the night sky, glowing dots that give Dark Constellations its visible, traceable structure. However, I would argue that what is most valuable about the book is everything in between those points, the shapes of fantastical creatures and unimaginable technologies that begin to emerge from the dark.

Nina Perrotta is an assistant blog editor at Asymptote. Since graduating from Brown University with a degree in literary translation, she has worked as a translator and ESL teacher. She recently completed a Fulbright scholarship in Curitiba, Brazil.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: