The April Asymptote Book Club selection sends us to Lebanon for the first time, trailing the footsteps of protagonist Samir as he searches for his father and “struggles to resolve the contradictions and scars of his upbringing into a cohesive identity.”

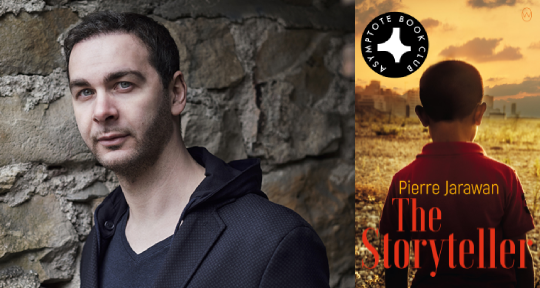

Pierre Jarawan’s debut novel, The Storyteller, “does for Lebanon what Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner did for Afghanistan, [pulling] away the curtain of grim facts and figures to reveal the intimate story of an exiled family torn apart by civil war and guilt.” The English version of the novel, co-translated by Sinéad Crowe and Rachel McNicholl, is available thanks to World Editions.

Our Book Club, catering to subscribers across North America and the EU (still including the UK!), has now published titles from seventeen different countries and thirteen different languages, and there’s still an opportunity to sign up for next month’s title via our website. If you’re already a member, join our online discussion here.

The Storyteller by Pierre Jarawan, translated from the German by Sinéad Crowe and Rachel McNicholl, World Editions, 2019

Reviewed by Lindsay Semel, Assistant Editor

The protagonist of The Storyteller, Samir, is born in Germany to Lebanese parents who fled their country’s civil war in the 1980s. Like many of his real-life contemporaries, he struggles to resolve the contradictions and scars of his upbringing into a cohesive identity. Grazing liberally from various cultures for its influences and allusions, Pierre Jarawan’s debut novel weaves between a past that feels too recent to be considered one, a present that feels too immediate to be already written about, and a future too intangible to trust.

The singular eponymous storyteller fragments into three distinct characters as Samir, the protagonist and narrator, searches for his beloved father, who disappeared when Samir was a child. As in the iconic 1001 Nights, storytelling is not just a form of entertainment, but a solution to a problem, a form of appeasement that holds at bay powerful and dangerous forces. Without giving away too much, the same three characters, one of whom is Samir’s father Brahim, remind the reader of the biblical progenitors of the monotheistic religions, a reference which casts doubt on the possibility that the characters will discover a peaceful resolution.

The most successful element of the novel is exactly this lack of a truly satisfying resolution. Samir spends most of the novel delving into Lebanon’s painful history of partisan violence in order to fill the gaps in his own family’s story. Though Samir finds answers to many of his questions, those answers leave Samir personally, and his generation generally, with even more questions and a lot of work still to be done. The characters search for a sort of Holy Grail, a mystical solution to complicated problems, and they don’t find it. This element of the novel seems the closest to a realistic depiction of truth.

Unfortunately, some other aspects of the novel are less successful. The family scenes that precede Samir’s father’s disappearance are just a shade too rosy, and the main female characters—Samir’s mother, sister, and love interest—are all essentially the same: sweet, pretty, faithful, and patient. Alina, Samir’s younger sister, is an angel from her birth to her early marriage. She doesn’t even hold a grudge against Samir for abandoning their relationship. Yasmin, Samir’s childhood friend and eventual fiancée, is beautiful, intelligent, ambitious, unflagging in her support, and always smells excellent—“a delicate mixture of honey and musk.” For no apparent reason other than their shared history, she allows herself to fall in love with him. She persists in her career seemingly without his taking any interest and meanwhile, with minimal exasperation, bears his egocentrism.

Samir and his father, as you may have already understood, are easy characters either to sympathize with or to condemn. The same could be said for Lebanon, itself a character in this narrative. Their challenge is to construct a viable future on such an uncertain foundation. To believe in success is a mandatory leap of faith.

Lindsay Semel is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote. She holds a BA in Comparative Literature and works as a freelance editor from her home on a farm in Northern Portugal.

*****

Read more about the Book Club on the Asymptote blog: