Inari Sámi Folklore: Stories from Aanaar by

Whatever the cosmopolitan politics of many people living in cities like London, New York, or Paris, the majority of museums in such places continue to struggle with the colonizing narratives forwarded not only by the layout of the physical space of the museum—a prime example being the room dedicated solely to Egypt, separate from the rest of the African continent—but also by the fact that many objects within these collections were stolen, looted, or otherwise removed from the communities that produced them.

Should these objects be returned or, in an argument that many see as dripping with colonial paternalism, are they indeed “safer” under the protection of Western institutions? One only need think of the ongoing controversy surrounding the so-called “Elgin” Marbles and their possible repatriation, or any number of recent developments concerning Native American peoples in the United States requesting the return of sacred objects, to understand how such objects touch on themes like intellectual and cultural sovereignty in the twenty-first century. The “Elgin” Marbles may have inspired Keats’s meditation on truth and beauty, but how would these same marbles appear, at a distance, to a poet writing from Greece during the Romantic period or in the age of Brexit? How would the nature of the marbles’ famed “truth” and “beauty” appear to someone who understood them as a piece of cultural heritage that had been looted for the express benefit of a cosmopolitan other? What would the return, or so-called repatriation, of such objects mean not only for those who have been robbed of such items, but for the descendants of those who stole them in the first place?

Although perhaps a commonplace by now, it remains worth stating that literary study itself is not immune from these dynamics. For example, non-alphabetic forms of script such as that found on what are most likely Mayan ceramics are all too often reduced to non-verbal visual art. Although disciplines like Anthropology, Archaeology, and Folklore certainly valorize these so-called “non-Western” traditions, they can also give literary scholars the freedom not to recognize these traditions as such, in favor of focusing on “real” literature.

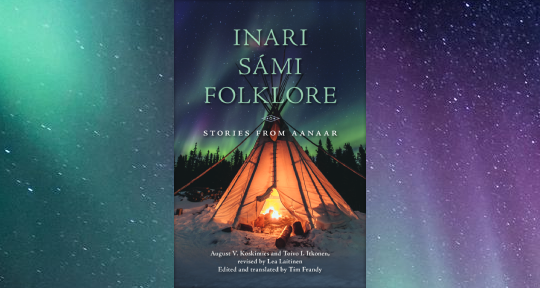

This is perhaps a useful way of understanding Tim Frandy’s English translation and edition of August V. Koskimies and Toivo I. Itkonen’s 1917 dual-language Inarinlappalaista kansantietoutta: as a work of intellectual and cultural repatriation that re-asserts Sámi intellectual and cultural sovereignty within the field of global literature. At its core, the work consists of works of Sámi-language oral literature that Koskimies collected and transcribed in the Sámi town of Aanaar in northern Finland in 1886. As Frandy notes, while Koskimies’s primary focus was scientific, focused on his own research in linguistics, the original production of the book took place at a time when European nation-states were seeking supposedly pre-modern cultures within their national borders as a way of buttressing a sense of autochthonous national identity. From the perspective of nineteenth-century nationalism, a culture like that of the Sámi might provide fertile ground for the elaboration of such nationalizing projects given that they are an Indigenous people whose whose ancestral territory, or Sápmi, spans large swathes of land on either side of the Arctic Circle. Indeed, Sámi presence in Sápmi, which includes parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula, dates back millennia. With parallels to more famous projects, like that of the Brothers Grimm, such a projectas Koskimies’ uses folklore as a way of elaborating a national past, in many ways reducing “the folk” to cultural ancestors who happen to share the present of the folklorist. Itkonen later edited and translated the fruits of Koskimies’s labor into Finnish for publication in a dual-language Sámi/Finnish format in 1917. Some sixty years after that, in 1978, the text was published once again in an edition compiled by Lea Laitinen. Frandy’s edition thus intervenes in an ongoing process of the stories’ framing and reframing for different audiences over time.

As for the role an English-language translation plays in forwarding Sámi culture over a hundred years later, in the Introduction Frandy states that, in addition to the usual academic and non-academic audiences, he hopes that the text also appeals to “the growing community of North Americans of Sámi descent, who have limited access to English-language materials about their heritage.” In other words, on a certain level the text—particularly in translation—can be seen as reproducing Sámi culture in the twenty-first century. It not only reproduces the stories in terms of their content, but, keeping in mind Frandy’s appeal to North Americans of Sámi descent, also claims the English language as a legitimate medium for the expression of Sámi culture, thought, and literature. Moreover, Frandy’s edition openly rebels against the moment when these stories were first recorded and takes pains to flesh out the collection’s stories as being part of a living literary tradition among the people of Aanaar.

On the one hand, Frandy presents the reader with painstakingly researched biographies for most of the storytellers found in the original work, which underscores the fact that stories, even communally held oral ones, are nonetheless told in particular ways by particular people in a particular moment. Gaps in these individual histories, as well as the fact that the two women storytellers are acknowledged though unnamed, underscore the uneven nature of the context in which these stories were originally recorded. On the other hand, Frandy also takes pains to provide the overall collection with a deep cultural context. He not only includes stories and “jokes” omitted from the 1978 edition, which flesh out the broader literary context of the stories, but also begins each chapter with a brief introduction. Informative and very useful for the scholar and popular reader alike, these introductions serve to further ground the texts generically and to reinforce the thematic connections across the stories themselves. While Frandy admits that these introductions are limited in their overall scope, they nevertheless prod the reader into reflection on the collection, individual stories, and Sámi culture as a whole.

The selection of stories provides a window, however small, into literary oral storytelling culture of the Sámi of Aanaar, Finland, as practiced in the late 1800s. Despite the collection’s aforementioned limitations in terms of gender (indeed, the only female storytellers are the two anonymous women), the collection does a better job than many similar collections of representing a wide range of stories. Legendary narratives like those concerning the stállu, a “vaguely troll- or ogre-like” being, stories from the legend cycle of the figure Päivän Olavi, and universal tales like “The Poor Boy and the King’s Daughter” exist alongside more shocking fare like “The Man and the Bear,” a story in which a farmer not only tricks a bear into castrating himself, but features a borderline pornographic ending in which the bear, in the most Freudian way, mistakes a woman’s vulva for a castration scar. This combination of the bawdy and the heroic prevents the collection from falling into the realm of puerile romanticism and reminds the reader that the Sámi are as human as anyone else. In addition, they throw into sharper relief the fact that, as Frandy himself notes, “stories that definitively centralize women’s experiences are absent from this collection,” which in turn underscores the role that Koskimies, as an outside male observer, played in shaping the original collection, as well as the wealth of female stories that undoubtedly exist.

In calling attention to the fullness of Sámi storytelling traditions through the volume’s re-edition and translation into English, Tim Frandy has done an excellent job of handling the material and communicating its lasting importance to a contemporary audience. As a model of narrative repatriation that reasserts a kind of literary sovereignty, the text demonstrates how even texts and monuments taken hundreds of years ago in the name of nationalizing projects can be re-appropriated, re-signified, and ultimately returned to their communities.

Paul M. Worley is Associate Professor of Global Literature at Western Carolina University. He is the author of Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures and with Rita M. Palacios is co-author of the forthcoming Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (2019).

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: