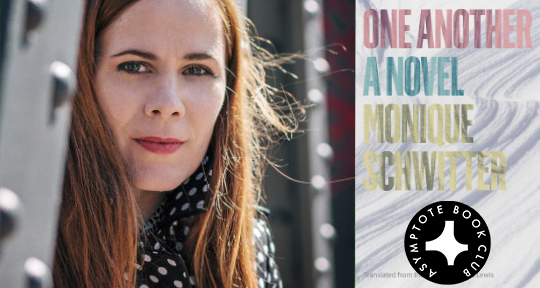

Monique Schwitter’s multi-award-winning One Another, a contemporary set of love stories with classical echoes, was described in Switzerland as having “the gentlest gaze and the hardest kick.” The original (Eins im Andern) was shortlisted for the German Book Prize before winning both the Swiss Book Prize and the Swiss Prize for Literature.

Tess Lewis’ English translation, published by Persea Books, is our Asymptote Book Club selection for March, and is currently heading to our subscribers across North America and the EU. To join us in time for next month’s title, you can subscribe via our website.

One Another by Monique Schwitter, translated from the German by Tess Lewis, Persea Books, 2019

One Another is an honest novel about love. The narrator, who also claims to be the author, and in later chapters references writing and titling the earlier ones, finds out about the unexpected death of a former boyfriend, Petrus. This provokes her to describe every romance she’s ever experienced. She devotes a chapter to each. The best part of this book is an honest account of contemporary womanhood that is not pious, ashamed, or guilty. An undramatic consensus ends almost every one of these vignettes. She never begs anyone to stay. She has cheated but she isn’t consumed with guilt. Certain complications in these affairs lead the reader to expect the familiar sentimentalism of broken hearts, but the narrator is much too rational for that.

In one chapter, deliberately written as a fairy-tale, the narrator sees a stranger at a bar and promptly falls in love. He follows her as she leaves the bar and enters the woods. He tells a tale of a knight courting a beautiful woman. She says nothing. They end up in an abandoned men’s restroom where they devour each other. His name (Johannes) is never mentioned again. This is not a love story that holds itself above the merely carnal. In a later, even more provocative chapter, the now middle-aged narrator navigates the advances of her seventeen-year-old student.

The narrator does not want to be provocative; she wants to tell the truth. It’s entirely realistic that a middle-aged teacher might be flattered by the sprawling glances of her student. This novel admits that such experiences, however fleeting, are continuous with sacred, eternal love. If such a thing exists, it certainly at least borders, if it isn’t completely mixed up with, lust or even familial love. In one of the most vulnerable and delicate passages, which reminded this reader of forms of childhood intimacy so total as to be embarrassing, the narrator recounts bathing with her older brother, her then-protector. They giggle while secretly tinkling. Only they know. These chapters are not stories of failed relationships; they are stories of a woman trusting herself and giving herself to others without regret.

She intends to write the last chapter about her husband, but that isn’t how it works. She acknowledges, in writing this work, that the place her conscious mind wants to accord to her husband is in fact occupied by memories of past romances and by a not-yet extinguished desire. That this acknowledgement is not intended to be scandalous or fraught with guilt is the strength of this novel and the measure of her freedom.

Photo credit: Matthias Oertel

Chris Power is an assistant editor at Asymptote who lives in Brooklyn.

*****

Read more about the Book Club on the Asymptote blog: