March brings with it a host of noteworthy new books in translation. In today’s post, Asymptote team members cover two novels set in the early twentieth century: Ida Jessen’s A Change of Time and Marcus Malte’s The Boy.

A Change of Time by Ida Jessen, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken, Archipelago Books (2019)

Review by Rachael Pennington, Assistant Managing Editor

Weaving together diary entries, poems, letters (both opened and unopened) and song, Ida Jessen’s A Change of Time, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken, is a stirring reflection on death and mourning, loneliness, and female identity in a changing 20th century Denmark. Fru Bragge—almost always referred to by her married name—has just lost her husband. During a loveless marriage spanning more than two decades, she endured Vigand’s lack of affection and derisive comments in silence. Although she has finally gained her freedom in losing him, she has also lost all direction in life:

I feel like a person standing in a landscape so empty and open that it matters not a bit in which direction I choose to go. There would be no difference: north, south, east, or west, it would be the same wherever I went.

It is in this vast landscape, the heathlands of Denmark, that she begins to sift through her memories, uncovering the girl she was before she became Fru Bragge. During the day, she welcomes courteous visitors who come to pay their respects and packs away her late husband’s belongings for donation; during the evening, after darkness has fallen and the oil lamp in the window of her empty home is lit, she feels most comfortable. Here, surrounded by a “silence greater than silence” she writes in her diary, giving voice to a part of herself she had almost forgotten: “Thinking back, I almost feel envious of that young school-mistress. In fact, there is no almost about it.”

It is through this rediscovery of people and places from her past that she begins to rebuild her life in the present. As we learn through her diary entries between 1905 and 1932, this was a time of change for Denmark and its women: from women gaining the vote and the first women’s movement to the passing of equal opportunity laws. Yet, with Vigand by her side, time seemed to halt for Fru Bragge, and now she must make sense of a world she no longer recognises:

We were married for twenty-two years, and although it has been a time in which many things have happened—a world war, motor cars, electricity, women’s suffrage—indeed an entire world would seem to have wound down and been replaced by a new one, I would still venture that those years have been one long and unbroken day.

For me it has been a quiet time.

Despite now forming part of the community of “unseen” widows, Fru Bragge dares to be seen: she obtains a driving license despite being the talk of the village—“It has caused a stir that I have become a motorist”; she finds solace in Hilda, also a widow, in a friendship Vigand would have never approved of, and she eagerly takes on the position of librarian.

Fru Bragge does get on with her life, yet her grief is present in each line she writes at lamplight. Her mourning is a responsibility that she bears with graceful humility, and, through Ida Jessen’s eloquently translated prose, we are reminded of “the deathly circumstance of our human life”. It is through these beautifully rendered recollections of the past and musings on the present that Fru Bragge can conclude, along with the many changes it brings: “time is more than sufficient”.

It is in the final pages of the novel that Fru Bragge is addressed by an old school friend and we learn her first name. Considering the unfamiliar name, we ask ourselves if this is the “change” she was longing for all along.

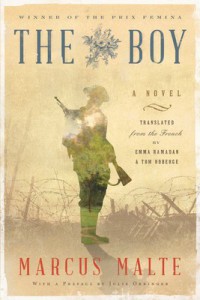

The Boy by Marcus Malte, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge, Simon & Schuster (2019)

Review by Filip Noubel, Editor-at-Large for Central Asia

“Even the invisible and the immaterial have a name, but he does not. Though hard to believe, the only evidence of his existence that remains is this.” “This” is Marcus Malte’s dark and intriguing novel The Boy, which won the Prix Femina in 2016 in his native France. Known and celebrated as a crime novelist, Malte plants his plot in familiar literary ground: the bloody Grande Guerre, as the French name World War One. Fractured skulls, severed limbs, entrails of humans and animals litter the ground. But something is amiss in this all-too-recognizable story: the main character, the Boy, whose presence feels more like an absence over the nearly 500 pages of the book.

The Boy has an unusual childhood: he is brought up in the wild by a lone woman, his mother. In a world devoid of other humans, of language, nature is his only companion. Primeval, brutally uncompromising, unabashedly playful: “On a riverbank he plays by splashing the swarms of tiny grasshoppers around his feet, those mischievous and Lilliputian escorts. In a field of lavender he floats on a flying carpet woven by a swarm of blue butterflies. He always makes sure to urinate on the domes of anthills so he can watch the hordes of panicked workers file out. These are the pleasures offered to him that he accepts.”

As his mother dies, those pleasures come to sudden halt, and the novel appropriately turns into a Bildungsroman. Encountering other humans, the Boy begins a new kind of education. Adopted by villagers, he experiences work and the scale of human emotions. Blamed for what he has not done, he is chased and rescued by a fist-fighter, the “Ogre of the Carpathians,” who takes him on as his son and assistant in his shows. The Boy finally gets exposed to the intricate rules of society, is taught human language, but he will never speak. He will not let his thoughts be translated. His life journey continues as he meets a woman, Emma, who literally crashes into his life at the wheel of her car, and falls in love with him. As the war catches up with them, she writes torrid erotic letters, but she, too, is unable to crack his silence. The Boy remains a mirror, absorbing the projections of others, puzzling the people around him, including the reader. And this perhaps is where Malte is at his best in this novel. What starts as Rousseau’s tale of the “Bon sauvage” (Noble savage), and seems to evolve into a traditional Bildungsroman, bifurcates into bitter and dark irony.

The Boy has observed and absorbed society, yet in the end nature will claim him back. The company of humans is not the best choice to make, after all. But the attentive reader had been warned, in the early pages of the novel: “Often at nightfall he’s crouched in front of a small basin of stagnant water puddled in a rock. Contemplating his reflection in this mirror for several minutes. A piercing look, without blinking, until he manages to separate himself, detach himself from himself, make himself into a perfect stranger: friend or enemy, it doesn’t matter as long as it’s someone else. As long as there are two of them.”

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: