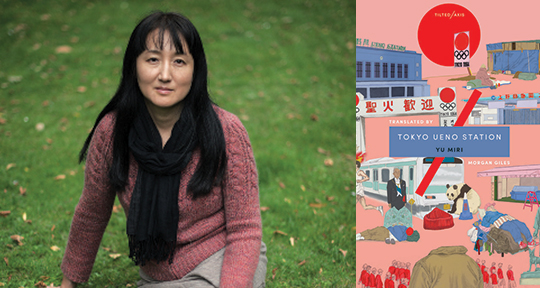

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yū Miri, translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles, Tilted Axis Press, 2019

Tokyo Ueno Station, originally published in Japanese in 2014, is Yū Miri’s latest novel to arrive in English via the efforts of translator Morgan Giles and publisher Tilted Axis Press. Yū Miri was born in Yokohama, Japan, as a Zainichi, or a Korean living permanently in Japan. In 1997, she was awarded Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize for her semi-autobiographical novel Kazoku Shinema (Family Cinema). Her past writing has explored damaging family relationships and outsider identity in a predominantly homogenous Japanese society.1

In Ueno Park, one of Tokyo’s most famous public grounds, the blue tents of homeless communities, or “squatters,” have become an unfortunate icon. A simple Google search of “homeless Ueno Park” will return videos, articles, and even tourist reviews of the park, detailing the homeless camps found there. In Tokyo Ueno Station, Miri tells the story of a homeless man named Kazu who lives in one of these camps. Told from Kazu’s perspective, the novel reflects on the tragic events that landed him finally under the blue tents of Ueno Park. But no story can exist or be told in isolation: Yū Miri brings the periphery of tragedy into focus in dreamy, kaleidoscopic visions, intertwining Kazu’s past, the history of Ueno Park, and the state of modern Japanese society. Tokyo Ueno Station is a shattered mirror of prose, made of misshapen shards that don’t always connect but together reflect an image of a lost life and inevitable misfortune.

Kazu’s story begins in the form of a poem, a self-spoken elegy in which he laments his entire life, which he views as a disorienting and regretful failure. The poem serves as a platform from which to dive into the story. As many good poems do, it leaves a space for the reader to fill with meaning and interact with. In this case, the space of the poem is filled by the subsequent narrative. The novel is punctuated throughout by non-chronological flashbacks which portray cornerstone moments in Kazu’s life. Some are characterized by undertones of love—a distant father and his children, briefly reunited, hands held walking toward home. The majority of the flashbacks, however, are tragic and swift, like a flash storm in summer, like an unforeseen death. As Kazu’s story is unearthed, the prelude poem becomes imbued and enriched by the melancholic life it represents.

Fate is a major theme throughout the novel. In the prelude, Kazu says of his life, “I had no luck.” Later in the novel, when his son passes away, Kazu’s mother says through spilling tears, “You never did have any luck, did you?” Though he lived a life of sacrifice and familial duty, a life that Japanese society would deem virtuous, Kazu is inundated by senseless loss. As Herman Hesse has said, “[M]an suffers destiny. Destiny is earth, it is rain and growth. Destiny hurts”—and this seems to be the entire thesis of Tokyo Ueno Station. Along with the literal acts of fate, Miri manifests fate symbolically in the form of rain. In the prelude, Kazu introduces the symbol with this statement: “[M]y eyelids twitched and trembled as if they were being hit by raindrops . . .” In a later scene, it rains and two old women under umbrellas discuss a stepmother’s cooking and the opening of a new Starbucks near Ueno Park. The carefree conversation suggests that these two are untouched by the cruel hand of fate, creating an acute juxtaposition with the homeless encampment they walk past. In another scene, Kazu lies awake in his tent during a rainstorm:

Raindrops suddenly began to fall, wetting the roofs of the huts. They fall regularly, like the weight of life or the weight of time. On nights when it rained, I couldn’t stop myself from listening to the sound, which kept me from sleeping. Insomnia, then eternal sleep—held apart from one by death and the other by life, brought closer to one by life and the other by death, and the rain, the rain, the rain, the rain.

It rained on the day that my son died.

Rather than solely exploring what it means to suffer at the hand of fate, Miri asks how that must feel in a world where those in power coexist in seemingly uncaring prosperity with the powerless. Tokyo itself is painted and characterized by the presence of its homeless inhabitants, communicating with them via signs often translated in alternative, simplified terms. The government never communicates directly with the homeless, only passively through signposts, and this small detail reveals the lack of understanding between the two groups. The city government is cold and distant, and the conversation is always one-way—an apathetic dictation that mirrors Kazu’s destiny. In one of the final scenes, the Emperor and Empress parade by Ueno Park and glance over at the displaced homeless people: “The pair gave us a look which could only be described as gentle, and a smile came across their innocent faces, ones that had never known sin or shame.” Kazu, born the same year as the Emperor, is wrought with emotion, and the reader feels it too—personified suffering and opulence meet for a moment, and the contrast is acute.

The novel also features a series of mini history lessons on Ueno Park, provided by a character named Shige. Shige also lives in a homeless encampment in the park and is the closest thing to a friend that Kazu has. He recounts how Ueno Park had served as a safe haven during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, how victims were temporarily buried in the park during the American firebombing of Tokyo, and so on. Through these recollections, Ueno Park is revealed as a place that has seen its fair share of traumatic events. By weaving the park’s history into the narrative, Miri successfully evolves the setting of the novel into a character in its own right. Ueno Park arises from the background as a complement to Kazu’s character—a partner in pain, a sympathetic place to rest his head.

The intertwining of narrative styles can be disorienting at times. Though the novel is technically told from Kazu’s first-person perspective, his voice often dissolves into the background in favor of a history lesson from Shige or an observational perspective of present-day Ueno Park. The latter perspective is voyeuristic and listens in on strangers’ conversations, even following a couple of women through an exhibition featuring 169 of Redouté’s rose paintings. In this section, we get descriptions of very specific roses interlacing mundane conversation between the two women:

Rosa gallica purpuro-violacea magna, the bishop rose: deeply colored, tinged with black, the outer petals of this rose turn up once past its peak, while the inner petals, just beginning to bloom, are purplish red . . .

“Are you going to go to Nagano again?”

“Back to Yatsugatake? No, never again. I can’t. Takeo and I always went together, anyway.”

Translated by Morgan Giles from Miri’s original Japanese, the voice of the English text has a certain vague, indistinct quality to it. Though the novel begins with a tangible first-person narration, that voice and its personality become diluted in descriptions of mundane activity around Ueno Park and its history. Even when the first person style returns to the forefront, some phrases feel distinctly non-idiomatic: “I heard the sound of water gushing from the rain-spouts. It must be a rather big downpour . . .” It’s possible that Giles chose to favor linguistic accuracy over literary embellishment, the former being a formidable challenge in and of itself. And that is not to say that there aren’t some standout quotes in this translation as well: “To speak is to stumble, to hesitate, to detour and hit dead ends. To listen is straightforward. You can always just listen.”

With Tokyo Ueno Station, Yū Miri is experimenting, abandoning a more defined narrative structure and style for something more poetic, loose-fitting, and juxtaposing. One loses track of the distinct and disjointed pieces and instead perceives the poignant whole, the tragic story of a man living under one of the many blue tents of Ueno Park.

Ben Saff is an avid reader, writer, musician, and technologist currently living in Philadelphia. He is a Responsive Layout Designer at Asymptote. He creates music as a part of the alternative rock band Kintsugi. His personal writings can be found on Medium.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: