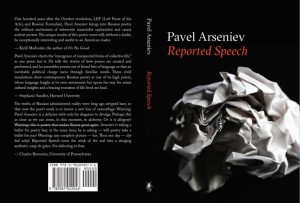

Reported Speech by Pavel Arseniev, Cicada Press, 2018

Reviewed by Paul Worley, Editor-at-Large

I tell my students that literature does things, but I prefer to do so in even less polished terms. From a more abstract perspective, I see current attacks on the humanities (especially literature) in the United States and elsewhere as being so vicious precisely because of the fact that literature does do things. It changes how we, as humans, relate to and understand others, as well as ourselves.

That said, there are moments when I profoundly doubt this. For example, I was recently discussing the fabricated crisis at the US-Mexico border and Trump’s wall with someone I had just met. During our discussion, this person informed me that Stephanie Elizondo Griest’s nonfiction All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the US Borderlands, a work that gives a nuanced, highly sensitive portrait of the US-Mexico border, actually serves to justify that border’s further militarization. It was like being told by someone with a very serious face that Shelley’s “Ozymandius” is a laudatory poem on the subject of indelible human achievement or that Swift’s A Modest Proposal provided a brilliant roadmap for the betterment of the Irish economy. And yet, even when my doubts about literature and its power dominate my thoughts, events like the murder of Iraqi novelist Alaa Mashzoub snap me back to reality. Literature matters, so much so that in other parts of the world literature can get you killed, even as I safely type this up in my home in the United States. Perhaps this will soon be the case here, too.

This is precisely how I understand the various interventions of Pavel Arseniev’s Reported Speech. In a bilingual Russian-English format, Arseniev’s work articulates intimate, defiant, and at times desperate responses to a world in which culture seems to be increasingly prefabricated, predetermined, and designed to numb the mind and soul. “***(Reports from the Field),” for example, provides us with a list of political and economic happenings before ending,

Also, the Russian Bureau of Consumer Protection has expressed concern

over the recent rise of websites

containing ambiguous information,

which is difficult to interpret.

Which after all, at least in the English translation, what precisely is difficult to interpret? The website containing ambiguous information? The rise in such websites? The pronouncement by the Russian Bureau of Consumer Protection itself? Of course the reader alert to matters of translation will be tempted to defer to the original text in Russian, and yet here the poem (and perhaps in the original as well) has precisely placed its finger in one of the great open wounds of the early twenty-first century: interpretation itself has become difficult, if not impossible, awash as we are in information, “Fake News,” and attempts to weave such detritus into an easy consumable narrative. There may be a there, there, but it is likely not the there we think it is.

Exposing the absurd vagaries of the present moment is where the volume shines as a tremendous piece of internationalist literature. In a gesture reminiscent of the work’s title, the poem “***(l’influence)” begins with an epigraph from a train car that states, “If you haven’t been vaccinated this season, don’t bother. The vaccine against the new virus hasn’t been invented yet.” Taking up this advice, the poem then develops its central conceit of non-vaccination against such vague threats despite the fact that the epigraph could equally be official instructions from a government bureau or graffiti. Either way,

if you are not vaccinated

this season

then don’t make a fuss

don’t make promises.

An italicized section tells us that,

Meanwhile in Belarus, they’ve gathered 820 tons of

high-quality blueberries. But they’ll ship them to

Poland, to Germany and Iceland.

What is happening? What is going on? These read as unrelated bits of information whose sole claim to coherence lies in the fact that they are juxtaposed in the poem. Again, the reader takes up the increasingly impossible yet mundane task of interpretation.

And yet for all of the absurdity the volume draws upon, the final poem maintains that,

We don’t need

augmented and improved reality

what we need

is an updated

and expanded

edition.

Through art like Arseniev’s poetry, we gain a toehold, however momentary, from which we are better able to grasp the present and prepare a future.

The volume itself contains both a Foreword by Kevin M. F. Platt and an Afterword by Sergey Zavyalov. Staying true to the work’s content, the former is in monolingual English and the latter in monolingual Russian, a move which will frustrate some readers while producing in others a self-knowing smirk. Platt’s Foreword, “Pavel Arseniev’s Intervention in Lyric,” does an excellent job situating the poet, his politics, and his work within contemporary Russia, and provides the reader with a sense of the milieu in which Arseniev came of age in the early 2000s. The poems themselves are drawn from several volumes published from the year 2008 to the present, and definitely leave the reader wanting more. As a keyhole into contemporary Russian experimental poetry, the volume should find a broad readership in the English speaking world, and in the United States in particular, where the country’s political future (or lack thereof) is bound closer by the day to that of Russia, Putin, and his cadre of oligarchs. In essence, the book represents poetic strategies for resistance and survival under fierce oppression, underscoring that literature matters, as well as how it does things.

Paul M Worley is Associate Professor of Global Literature at Western Carolina University. He is the author of Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures and with Rita M Palacios is co-author of the forthcoming Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (2019).

Pavel Arseniev (b. 1986) is a Russian artist, poet and theoretician. He is also known for editing and galvanizing intellectual forces around the St. Petersburg-based journal of poetics and theory, Translit – an activity for which he received an Andrei Bely prize, Russia’s most prestigious literary award – and for inventing the slogan that became a rallying cry of the 2012 anti-Putin protests. His poems have been translated into English, Italian, Danish, Dutch, Bulgarian, Polish and Slovenian.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: