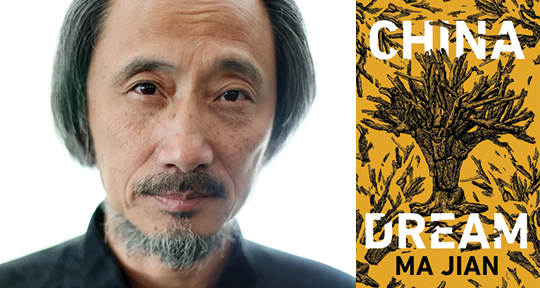

China Dream by Ma Jian, translated from the Mandarin by Flora Drew, Penguin Books.

The controversy over the cancellation and restoration of two public talks involving Chinese dissident writer Ma Jian by the venue provider, Tai Kwun, in last November’s Hong Kong International Literary Festival, has added to the topicality of Ma Jian’s newly published translated work, China Dream. Bearing a politically sensitive title that blatantly alludes to President Xi Jinping’s project of rejuvenating the Chinese nation, his “Chinese Dream” as portrayed in the novel is quite an oddity as a translated work. The translated English version was published before the original Chinese version, which is forthcoming from a Taiwanese publisher; however, this is within expectations considering the sensitiveness of the subject matter. Ma Jian’s scathing critique of autocracy not only targets the national project of the present Chinese government but all forms of rigid, state-controlled policies that annihilate individual subjectivity.

China Dream is in line with the tradition of dystopian fiction in its imagination of negative government. Different from its Chinese predecessors, such as Lao She’s Cat Country, which is more akin to a Swiftian satire, or Chan Koon-chung’s The Fat Years, whose dystopian vision is embodied in the form of science fiction, China Dream is more psychological, interweaving an increasingly uncanny present with a spectral past that eventually encroaches upon it. China Dream is about the will to oblivion and subsequent self-destruction of a Chinese officer who rises to power after his betrayal of his Rightist parents in the Cultural Revolution. The narrative centers on how Ma Daode, the director of the fictional China Dream Bureau, who is simultaneously a representative of state corruption and moral guilt, falls from his prime, and kills himself in a paradoxical moment of delirium and recognition.

As the director of the newly established China Dream Bureau, Ma Daode takes up the authoritative role as the engineer of President Xi’s national project. The proposal of developing a microchip that will be implanted in the residents of Ziyang City to wash their private memories and dreams away in order to be replaced with the China Dream seems to establish a sci-fi tone for the novel. But the expectation is soon overturned as the narrative about the present is intruded upon by the past memories of Ma Daode, often unconsciously and uncontrollably. The intervention attempts to draw a parallel between the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s and President Xi’s “China Dream”: while the former aimed to banish history, the latter extinguishes personal dreams and memories, both leading to the devastation of individual self. While the funding for the development of the China Dream Device is on hold, Ma launches the “Golden Anniversary Dream” as propaganda promoting the China Dream, which features a mass golden wedding anniversary celebration for fifty old couples who have been married for fifty years. Ma’s attempt to utilize the emotional pride of others becomes his own undoing when one of the couples accidentally induces him to publicly reveal his haunting memories of the Cultural Revolution.

Ma Daode longs for the elimination of his past self so that his power can be restored: “He is fed up of his adolescent self intruding on his thoughts. It has caused him the loss of his chauffeur-driven car and the suspension from his job. If I don’t destroy my past self, I will lose everything.” The tug between Ma’s power thirst and guilty past drags him further into his psychological swirl. Ma seeks help from a Qigong healer, Master Wang, to bring him Old Lady Dream’s Broth of Amnesia from the netherworld in order to erase his memories, and the narrative’s absurdity is heightened with this superstitious turn. In Chinese mythology, the Broth of Amnesia is only served to ghosts when they cross the Bridge of Helplessness after death. Unable to obtain the real Broth of Amnesia, Ma gets a recipe from Master Wang to make his own version of the broth. One of the memories he intends to expunge is the demolition of Yaobang Village. Although Ma is merciless in the destruction of the place of his exile, where he received re-education, the experience affects him. Despite the difference in status, Ma’s unfreedom is not dissimilar to that of the villagers or any other victims who have to subjugate themselves to the will of the state. That’s why when Ma climbs up the Drum Tower of the Ziyang City, attempting to drink the self-made Broth of Amnesia, renamed the China Dream Soup, to free himself, he is mistaken by onlookers for a poor migrant worker or peasant petitioner. His address to the crowd prior to his fall from the Tower is his most genuine yet, and its contents resonate strongly with the audience. In this way, one realizes that every subject of the state with a painful past is in need of amnesia: a man wishes to wipe out the memory of his wife, who left home to become a factory worker in Guangdong and did not return; a woman cannot forget her newborn son, who was killed by a family-planning doctor. They desire to renounce their past selves and embrace a new life.

However, Ma Daode is destined to belong nowhere. He has neither a way to atone for his past nor a hardened mind to persist with his mission due to his “debt of blood.” When Ma again meets the old woman who spoke in the “Golden Anniversary Dream” ceremony, her words confront him with his predicament: “You won’t be allowed across the Bridge of Helplessness. You’ll be flung into the River of Forgetting and will spend eternity as a feral ghost.” His inclination to repent and desire for forgiveness from his parents are offset by his nostalgic clinging on to his youthful zeal and commitment to the revolution. The brutal Ma, the ambitious Ma, and the remorseful Ma are integral to his identity. He asks: “But which Ma Daode am I?” His identity crisis culminates in a climatic realization of the connection between the Cultural Revolution and the China Dream through a slip of the tongue:

“Let us bid farewell to the past and sing in unison: ‘The Cultural Revolution is really good, really . . . ’ Forgive me, I mean: ‘The China Dream is really good, really good . . . ’ Just as he is about to sing ‘really good’ for the third time, Ma Daode sees his father, an English fountain pen clipped to the pocket of his white shirt and a two-toned brogue on his left foot, being dragged by Song Bin out of the Qingfeng Dumpling Store.”

Instead of shedding shameful tears, he drops his blood into the China Dream Soup. But without drinking it, he leaps off the Tower with a clear mind and attempts to embrace true freedom by embracing the void of death. Ma Daode is one of the many feral ghosts that haunt the China Dream: like the splintered tree branches of Ai Weiwei’s cover illustration, they are repressed and wretched individuals, crushed by the large machinery of the government and dictatorial revolution.

Charlie Ng Chak-kwan is Asymptote’s Hong Kong Editor-at-Large. She obtained her B.A. in English and M.Phil. in English (literary studies) from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2007 and 2009, respectively. She graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a Ph.D. in English literature. She is currently an assistant professor at the School of Arts and Social Sciences of the Open University of Hong Kong.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: