With our February selection, the Asymptote Book Club is taking subscribers back to school. Fortunately, Zsófia Bán’s Night School is a school unlike any other—populated by a cast of literary and cultural figures ranging from Frida Kahlo (and her double) to Laika the space dog. Each chapter of Bán’s textbook primer is filled with ‘defiant irreverence’ and the perfect combination of wit and profundity.

We’re delighted to be sending our subscribers one of the year’s most coruscatingly original short story collections, in Jim Tucker’s superb English translation. If you’d like to join us in time for next month’s Book Club pick, you’ll find all the information you need on our web page. Once you’ve joined, head to our Facebook group to meet other Book Club members and contribute to the discussion. We look forward to seeing you there!

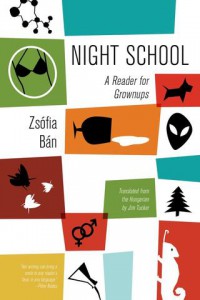

Night School: A Reader for Grownups by Zsófia Bán, translated from the Hungarian by Jim Tucker, Open Letter, 2019

Reviewed by Jacob Silkstone, Assistant Managing Editor

Let’s begin with a simple biographical detail: Zsófia Bán has spent much of her life in academia, and her first novel (originally published in Hungarian in 2007) is a textbook. It seems barely necessary to add that Night School is a textbook like no other.

Ostensibly divided into an assortment of subject areas (beginning with ‘geography/history’, and ending with ‘Hungarian’), Night School is an exercise in refusing to let readers remain passive. Each section, mocking the style of a school primer, ends with a series of questions and assignments. The question for the ‘chemistry’ chapter, for example, is:

Is it permissible for a lady chemistry teacher to scrunch up her eyes and say, I just lurve you my little bunnies? Can this be tolerated?

After reading up on ‘religion’, the reader is asked to ‘CALCULATE how many angels can fit on the head of a pin if each angel is approximately 45mm and faithless’.

The textbook itself is a miscellany of short stories, freewheeling between fact and fiction. Beethoven’s ‘Fidelio’ is retold as a ‘blog opera’; both Frida Kahlos are allowed to step out of ‘The Two Fridas’ painting, although one ‘[dreams] in Spanish and the other [counts] in Hungarian’; Flaubert proposes to Maxime du Camp, ‘goes whoring’, and is told to ‘get fucked’ by Louise Colet; Laika, the first dog in space, relates the story of her ‘eve of no return’.

Aside from her fiction, Zsófia Bán is perhaps best-known for her essays on imagery and visual arts: she has written extensively on both Sebald and Sontag, in addition to the role of images and photographs within the context of cultural memory. Each section of Night School is illustrated, but the images are a world away from the grainy, enigmatic black-and-white visuals you’d expect to find in a Sebald novel. In the ‘religion’ section, we find an image of a dog in a skirt, staring wistfully up towards the camera, while a page on Maxime du Camp and Flaubert is illustrated in the style of South Park. Rather than Sebald or Sontag, Night School recalls Andy Warhol. Literary and pop culture icons are redrawn in brighter, bolder colours, with a healthy dose of irreverence towards the narratives that bind together societies.

That defiant irreverence is Night School’s greatest strength. Other reviewers have highlighted the novel’s rebuttal of the ‘closed and ideologically committed’ system in which Zsófia Bán grew up, but Night School speaks with equal relevance to a contemporary audience. Bán is Hungarian, and her bursts of laughter in the dark offer a refreshing antidote to the rightward march of both countries. One thing Daniel Kalder’s Dictator Literature revealed, if it wasn’t already clear, was that despots are united by a complete lack of humour, in both writing and life. Night School offers us a world in which the underdogs of history are free to tell their own stories (literally, in Laika’s case), and boundaries are transformed and transgressed. Under the heading ‘religion’, two lesbians meet for a clandestine tryst at a zoo in ‘distant Borneo’. Homosexuality in Malaysia remains illegal, but the language used to describe the meeting is anything but coy:

the entire company of gods bore witness to us drinking, licking, sucking the manna out of each other to the very last drop, like hungry jackal pups, then again and again until the storm subsided.

In several stories, the great white male cultural figures of the past are re-examined with a healthy mixture of respect and scepticism: in addition to the lascivious Flaubert, we’re offered a pompous version of Longfellow (‘Henry, the national poet, writes verse like a bird sings . . . It hits Henry hard that people think just anyone can write poems’), and a continuation of Dangerous Liaisons via email.

Zsófia Bán’s textbook parody is a bravura performance, and perhaps it has more to teach us than we might initially think.

Jacob Silkstone is an Assistant Managing Editor for Asymptote. He was previously Managing Editor of The Missing Slate (Pakistan) and has worked at international schools in Bangladesh and Norway.

Image credit: Dirk Skiba

*****

Read more about the Book Club on the Asymptote blog: