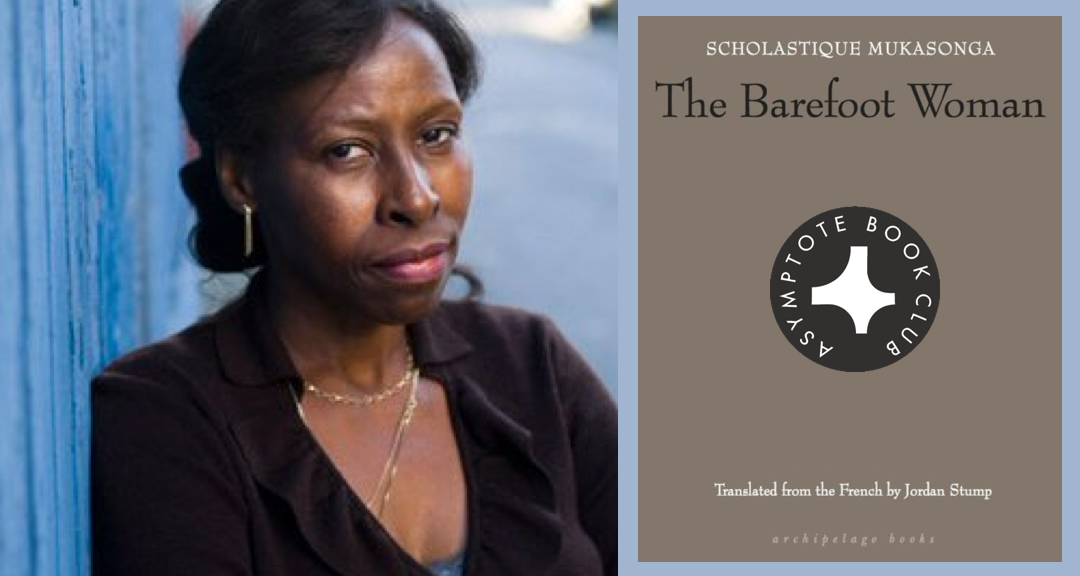

The Asymptote Book Club enters its second year with a first African title: Scholastique Mukasonga’s The Barefoot Woman, translated by Jordan Stump and published by Archipelago, is a moving tribute to the author’s mother, one of the victims of the Rwandan Genocide.

After visits to Turkey and Croatia in the previous two months, we again find ourselves confronting “the dark and bloody face of history” through the mirror of prose. Mukasonga’s homage to her mother, though, “radiates . . . with warmth and affection,” in the words of our reviewer. “This slim memoir,” says Alyea Canada, “is a haunted and haunting love letter.”

Head to our online discussion page to add your voice to the discussion on The Barefoot Woman. All the information you need to subscribe for future Book Club selections is available on our Asymptote Book Club site, together with a full overview of our first twelve months.

The Barefoot Woman by Scholastique Mukasonga, translated from the French by Jordan Stump, Archipelago, 2018

Reviewed by Alyea Canada

“You’ll have to cover me, my daughters, that’s your job and no one else’s. No one must see a mother’s corpse otherwise it will follow you, it will chase you . . . it will haunt you until it’s your turn to die, when you too will need someone to cover your body.”

Scholastique Mukasonga’s The Barefoot Woman, translated from the French by Jordan Stump, opens with a dreamy recollection of Stefania, Mukasonga’s mother, delivering this missive to her daughters. Despite taking these instructions quite literally, Mukasonga was unable to cover her mother’s body. In 1994 she lost Stefania and twenty-six other family members when the Tutsis were massacred by the Hutus in Rwanda. However, this isn’t the story of that genocide; this story is gentler. In a series of vignettes, Mukasonga tells the reader about brewing sorghum beer, interpreting omens, and courtship. It becomes a record of the ways Stefania, and the other Tutsi refugees, maintained dignity and survived while living in exile in the Bugesera. At its heart, this slim memoir is a haunted and haunting love letter to Mukasonga’s mother and the “beneficent Mothers, the benevolent Mothers . . . the ones the killers slaughtered as if to wipe out the very sources of life.”

In Cockroaches (2016, Archipelago), Mukasonga writes in detail about the violence her family suffered, but in The Barefoot Woman, violence is more a shadow overhanging the events described in its pages. Mukasonga devotes only a few paragraphs to how Belgian colonialism laid the foundation for genocidal hatred before shifting focus to the “tenuous survival” the Tutsis achieved. When the violence does move to the foreground, it is often to mark a shift in lives and traditions. When their home is raided by Hutu soldiers, Stefania begins running escape drills and marking a trail for her children to Burundi. However, more often the violence resides in the language Mukasonga uses. It lingers in the subtle shift of the phrase “in Rwanda” from a location to a memory of a place lost to the Tutsi refugees.

The book is peppered with words in Kinyarwanda, sometimes directly translated and sometimes defined through context, creating a tension deftly rendered by Stump. When discussing her mother building an inzu, Mukasonga refuses to name it in French because the words are too “contemptuous” to describe the straw-woven house central to her memories. These italicized words become a reminder that Mukasonga is not writing in her native language but in a colonial one. Her mother cannot understand the words used to “weave a shroud for [her] missing body.”

Despite the fate met by the women in the book, The Barefoot Woman doesn’t feel heavy. Some parts are quite funny, such as the lengths taken to find one girl a husband. But it is the final chapter, “Women’s affairs,” that radiates with a warmth and affection that is different from the rest of the book. In this chapter you feel the strength and courage of Stefania and the other mothers, but you also feel Mukasonga’s grief and the breadth of what was lost in 1994. In telling her mother’s story, Mukasonga returns agency to Stefania and the other women of her village. They become more than their deaths. Their bodies are covered.

Alyea Canada is an Assistant Editor at Asymptote. She currently works as a freelance editor and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

*****

Read more about the Asymptote Book Club here: