In today’s dispatch, Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Slovakia, Julia Sherwood, reports on the high points of the European Literature Days festival, which she attended in Spitz, Austria from November 22-25. This year’s festival, whose theme was “film and literature,” featured many of Europe’s best film directors and screenwriters alongside high-profile novelists and essayists.

What is the relationship between film and literature? How does narrative work in these two art forms and what is lost or gained when a story is transposed from paper to the screen? These questions were pondered during the tenth European Literature Days festival, amidst the rolling hills on the banks of the Danube shrouded in autumn mists, on the last weekend of November. As in previous years, the weekend was full of discoveries, with the tiny wine-making town of Spitz and venues in the only slightly larger town of Krems attracting some of the most exciting European authors, this time alongside some outstanding filmmakers.

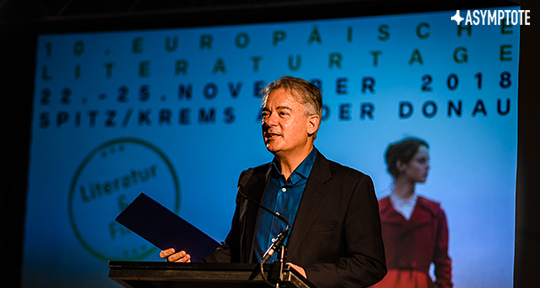

Robert Menasse and Richard David Precht. Image credit: Sascha Osaka.

Bookended by two high-profile events, the gathering opened with a discussion between Austrian novelist and essayist Robert Menasse and German celebrity philosopher Richard David Precht, moving at breakneck speed from the theory of evolution to a critique of the current education system, sorely challenging the hard-working interpreters. The closing event saw Bulgarian-born writer Ilija Trojanow receive the Austrian Book Trade Honorary Award for Tolerance in Thought and Action and make a passionate plea for engaged literature: “As a writer I have to live up to the incredible gift of freedom by writing not about myself but away from myself, towards society.”

The remainder of the weekend focused on this year’s main theme—film and literature—introduced by German novelist Katharina Hacker in a keynote essay. Her text probes the transformation that her novel, Die Habenichtse (The Have-Nots in Helen Atkins’s English translation), underwent as it was condensed into a film version, by using the “artistic means of light and human flesh.” Hacker spurns the notion of “authenticity” and mistrusts its apologists, putting her faith instead in things that are complex and unfolding, and in the freedom of expressing things that move and puzzle us. She sparred with Romanian scriptwriter (The Death of Mr Lazarescu) and novelist Răzvan Rădulescu (winner of the EU Prize for Literature for his novel Theodosius the Small), who is resolutely opposed to his books being turned into films, contending that they exist purely to explore words and ideas, and that film adaptations succeed only when they are based on plot-driven novels that are themselves based on a never-made film series.

Connections between real life and the novel were next explored by two artists pursuing their own unique, genre-stretching vision. Dutch director, screenwriter, and publisher André Schreuders has created his own film language, at the intersection between philosophy, poetry, fiction, and documentary. In his film Along Chapel Road, he visits locations connected to a milestone of experimental Flemish literature, Louis Paul Boon’s Chapel Road (De kappelekensbaan, 1953), quoting from the book but focusing on the images reflecting his own emotional and intellectual response to the novel. Schreuders has long been fascinated by the philosophical legacy and metaphysical aesthetics of Russian absurdist writer Daniil Kharms, having written a book about him and creating Phenomena & Existences No. 3, a visual installation for the Writers Union of St Petersburg, and a film of the same title. Tim Krohn, a German writer based in Switzerland, introduced his staggeringly ambitious project Menschliche Regungen, which he defines as “human emotions, features and facets” such as ambivalence, asexuality, cynicism, or desire, to give a few examples. Krohn drew up a list of some thousand Regungen, and went on to launch a crowdfunding campaign, asking each donor to pick one item on the list and be rewarded with a story about it. So far, he has written 111 stories, published in three volumes and featuring a set of eleven characters all living in the same apartment block in Zürich. If and when completed, the project will run to 15 volumes, comprising 7,500 pages; meanwhile, it’s garnering rave reviews in the German press.

On the second day of the festival, proceedings moved to the Kesselhaus cinema in Krems, where discussions with four women filmmakers were illustrated with clips from their films. Sadly, it wasn’t possible to fit complete screenings into the programme, but since returning home, I’ve been busy catching up on these remarkable films, having previously missed some of them (to my great shame), while others are yet to be shown in the UK. Hungarian director Ildikó Enyedi explained why she chose an unusual location for her 2017 film On Body and Soul (Testről és lélekről), the winner of the Berlin Film Festival’s Golden Bear and an Oscar nominee. Using space as a dramaturgical tool that goes beyond serving simply as a location, Enyedi has set her film in a slaughterhouse to show that her two main characters, who are quite damaged human beings, live real lives in a real, damaging environment. Acclaimed Bosnian scriptwriter, producer and director Jasmila Žbanić, whose 2006 film Grbavica grapples with the harrowing issue of rape as a weapon of war, chooses her locations as carefully as her actors. For her most recent movie, Love Island, co-scripted with Aleksandar Hemon, she found an isolated island hotel on the Croatian coast. Prompted by moderator Carl Henrik Fredriksson, founder of the online journal Eurozine, Enyedi listed Agnès Varda, Miranda July, and Claire Denis as her role models and revealed that her next project is an adaptation of the Hungarian Milán Füst’s psychological novel The Story of My Wife. Žbanić, who is currently planning a film about the Srebrenica massacre, was inspired by Jane Campion, Věra Chytilová, and Helke Sander.

Rosie Goldsmith, Kathrin Resetarits, and Olivia Hetreed. Image credit: Julia Sherwood

The role of women in film was also the subject of a conversation between Olivia Hetreed and Kathrin Resetarits, two scriptwriters at the top of their game, and Rosie Goldsmith, a UK journalist and founder of EuroLit Network. Despite the widespread perception that women have been breaking through the glass ceiling, their situation in the film industry is as difficult as ever, noted Britain’s Olivia Hetreed, BAFTA-nominated scriptwriter of Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, quoting the grim findings of a recent survey conducted by the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain, of which she is president. The report, which spans the past decade, found that TV shows and films written by women in the UK flatlined during that period, with no consistent improvement in gender representation: only 16% of working film writers in the UK are female, and only 14% of prime-time TV is written by women. Hetreed also talked about her radical re-imagining of Wuthering Heights (2011, dir. Andrea Arnold). When she first read Emily Brontë’s novel as she was growing up, she saw it primarily as a love story, but re-reading it years later, she realised it was just as much about hatred and racism, and took the bold step of making Heathcliff black. Kathrin Resetarits, Austrian director, scriptwriter, actress and advisor to Michael Hanecke, shared the creative process behind her script for Licht (Mademoiselle Paradis, dir. Barbara Albert). Rather than merely adapting Alissa Walser’s novel Am Anfang war die Nacht Musik (Mesmerized, trans. Jamie Bulloch), she based it on numerous other period sources. Most importantly, she changed the focus from the famous doctor Mesmer to his patient, the blind pianist Resi, allowing us to literally see the world through her eyes during the brief period when the treatment is working.

Coinciding with the global premiere of the new TV series based on Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, one of the liveliest discussions dealt with the phenomenon of TV serials. Austrian writer and publishing and media specialist Rüdiger Wischenbart summed up the main points of his paper “What Next? The Law of the Series. New storytelling in the old media,” which included the successful blending of commerce and art; the formula “keep it local, put writers at the centre of the production, and avoid adaptations”; ensure that the narrative pace remains unrelenting, amphetamine-driven. Further points—the power of Netflix and the industrialisation of writing—were illustrated by two of the panellists: Croatian investigative journalist and novelist Ivica Đikić, whose homegrown series “The Paper,” based on his script, was bought by Netflix after the success of the first two series, and is now marketed as a “Netflix original,” while Romanian-born German writer Ilinca Florian offered some hilarious examples of the pressures scriptwriters working in an industrialised environment have to cope with (Florian was this year’s official European Literature Days blogger and you can find a more detailed account of this and other sessions here).

The hills above Spitz. Image credit: Julia Sherwood.

As always, the highlights of the weekend were authors’ readings showcasing a variety of styles and talents. German writer Carmen Stephan’s It’s All True tells the story of a film by Orson Welles, which was meant to celebrate the incredible journey of four Brazilian fishermen on a raft that ended in disaster. Ivica Đikić’s novel Sanjao sam slonove ([I Dreamt of Elephants], not yet translated into English but available in Patrik Alac’s German translation Ich träumte von Elefanten) also has its basis in fact: two elephants Indira Gandhi presented to Yugoslavia’s leader Josip Broz Tito remained on the Brijuni islands off the coast of Croatia after his death. Gender-bending Danish writer, singer and performance artist Madame Nielsen read from her captivating and atmospheric novel The Endless Summer. Accompanied by a cello and guitar duo, Austrian literary sensation Vea Kaiser gave a spirited reading from her breakout novel Blasmusikpop (Oompah-band Pop), showing a joy in storytelling just like Georgian-born theatre director and novelist Nino Haratischwili, who defied naysayers by letting her first novel, Das achte Buch – für Brilka (The Eighth Book), run to 1,300 pages. Haratischwili’s family saga of six generations of women, spanning over a hundred years and moving from the Georgian countryside under Stalin to Berlin after the fall of the Wall, was published in 2014 and named book of the year. It is currently being translated into English, but rather than wait until next September, I decided to bring a copy back from Spitz even though my suitcase was already groaning under the weight of books purchased a few days earlier during my stay in Slovakia, as it’s surely just the book to cuddle up with during the holiday season!

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. Since 2008 she has been working as a freelance translator of fiction and non-fiction from Slovak, Czech, Polish and Russian. Her translations into English (jointly with Peter Sherwood) include book-length works by Balla, Daniela Kapitáňová, Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki, Uršuľa Kovalyk, Peter Krištúfek, Pavel Vilikovský and Petra Procházková; and, into Slovak, books by Tony Judt and Hamid Ismailov. She is based in London and is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Slovakia.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: