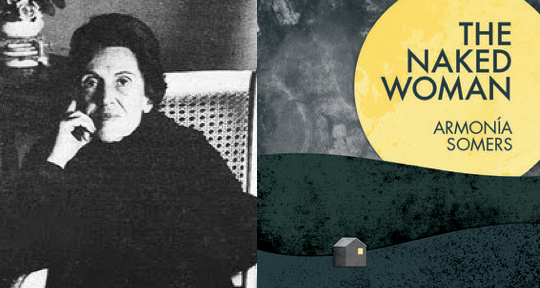

The Naked Woman by Armonía Somers, translated from the Spanish by Kit Maude, Feminist Press, 2018.

What could freedom from the pressures and expectations of society mean for a woman in Uruguay in the 1950s, and what might the impact of this freedom be on others? These questions are explored by Uruguayan author, scholar, and feminist Armonía Somers in The Naked Woman. Written in 1950, this is the first of Somers’ books to be translated into English. The novel tells an energetic and enthralling story through which Somers articulates a pressing need in society for people to find ways to escape prescribed roles, express desire, and renew one’s sense of self. The narrative focuses on the experience of the female protagonist, Rebeca Linke, and sheds light on the repressive context of 1950s Uruguay when, according to scholar Maria Olivera-Williams, “middle-class social mores proved particularly suffocating to women.” Somers explores the effects of these constraints on women and creates a subversive protagonist who creatively and successfully challenges these expectations by allowing herself to release her natural instincts and understand new forms of intimacy. Whilst the female experience is the focus of the book, Somers’ carefully-crafted novel reveals the effects that living in a society in which women are repressed has on both women and men. She achieves this by depicting male violence against women and the harmful effects of a lack of freedom of choice.

The Naked Woman begins with Rebeca Linke’s revelation of the failed hopes that she had pinned on her thirtieth birthday. This sense of disillusionment is the driving force behind her decision to abandon her everyday existence and move to the countryside: she is desperate to break the daily monotony of her life, to embrace freedom and to live in the present. She takes a train to a small cottage in a remote part of the Uruguayan countryside where she casts off her one remaining item of clothing, her coat, having abandoned everything else. As a result, her break with the past and her commitment to the here and now becomes urgent: “[s]he was beholden to the present, like water held in the palm of a hand.” When she ventures out into the night, she is immersed in a natural environment that she has never before experienced so intimately. This then extends to her own body: she discovers its uniqueness by touching it and she remarks upon changes that she had not previously noted. It is Somers’ focus on the present, the protagonist’s physical experience of each moment, and the centrality of the female body that make the book so compelling, exciting and enticing for readers today.

Kit Maude’s translation conveys the novel’s sense of urgency, often evoked through the careful rhythm of short sentences which nevertheless do not miss a single detail from the sensuous descriptions. The translation successfully evokes a sense of immediacy, the mixture of pain and pleasure that Rebeca experiences and the intensity of her heightened emotions at key moments. For example, the sensations of urgency, sensuality, fear, and desire coincide when Rebeca meets two young boys when she is crossing a field in the middle of the day. Terrified of her, they run to inform the residents of the nearby village where they live of their unusual encounter. The boys abandon their horse and whilst both the reader and the protagonist are aware of the potential threat posed by the villagers, Rebeca becomes fascinated by the horse, which, for her, represents all of life. She frees it from its harness to discover it has a wound:

“The twins would describe her nakedness vividly and a crowd would come after her. But they weren’t yet aware of the ancient source of her confidence. Aggravated by the sun and the fly’s thirst, the cut seemed to have grown into a trench around her feet, blocking her way. Driven by an uncontrollable urge, she kissed it.”

The reader immediately gains an insight into the disruptive force that Rebeca’s naked body becomes for the people that she meets, particularly because they are living under the pressure of the strict moral codes that she seeks to defy. The sensual descriptions of the elements on the protagonist’s body, the evocative detail given to the feeling of walking barefoot in the forest and her ability to do away with analytical thought and, instead, to act, mean that the reader is constantly reminded of Rebeca’s choice to focus on the present. She states, “I have done without codes and the thorns cut me for it”: the idea that women are punished for not conforming is present throughout the novel. The reader is reminded of this through the violence exerted upon the female characters by their husbands and by the frequent references to Eve, a name that Rebeca temporarily adopts but then rejects. In fact, immediately after she arrives in the countryside she enters a dwelling in the middle of the night and breathes the names of biblical and mythical female characters into the ear of a sleeping man. This shows the constant burden that these archetypal figures place upon women. At the same time, the fact that some of these women acted in ways that defied gender stereotypes, demonstrates their power to subvert and so we understand that Rebeca represents many women. Somers creates a voice for her protagonist to enable her to speak as a woman and for other women. In English, translator Maude conveys this sense of multiplicity and draws us to it, thus inviting us to identify with this group of women. As Elena Chavez Goycochea articulates in her critical afterword, in which she highlights the significance of Somers’ work in renewing ideas about women’s writing in Latin America, the author challenges the reader to question the ongoing impact of these traditional myths on the formation of ideas in society today.

Central to the narrative is the performance of ritual and the reader understands its significance through Somers’ use of a narrative voice which shifts between different perspectives. The night that Rebeca arrives at her new home she undergoes a kind of transformative ritual in which she casts off her former life and prepares for her new one. This is ritual as restorative process and forms a stark contrast to the type of ritual that the villagers who become obsessed with her and her presence experience. The villagers inhabit a world in which every event is planned and predicted and there is a “dearth of extraordinary experiences in their everyday lives.” They experience ritual as pure routine and this means that the mere awareness of the existence of the Naked Woman, after the two young boys alert the community, disturbs the order of their lives and shakes them to their very core. She begins to haunt their dreams, awakens thoughts that were repressed, even feared, and unleashes latent sexual desires. The Naked Woman gets beneath the skin of the villagers: she enters their blood. They simultaneously reject her for her immorality and invite her in by leaving their doors unlocked at night in the hope that she might visit them. Finally, the importance of religious ritual is paramount: after a long night in which the Naked Woman has infiltrated every part of the town, even the dreams of the priest, many of the residents come to confession. There is a striking contrast between the ritual which transforms Rebeca and gives her freedom and the ritual of routine which condemns the villagers to a repressed life. This serves to reinforce the idea that Somers’ creates a character who breaks with convention.

In her final encounter, Rebecca enters the village and meets Juan, who desperately longs to take her inside his house. She asks him, “What would you have done with me?” and he violently reacts by “roughly shov[ing] her away, his jaws and eyes squeezed shut.” This demonstrates the ingrained resistance to the open expression of desire, even when, as Juan says, “it’s the one thing you want to do before you die.” In this short encounter, the characters move from experiencing feelings of embarrassment to freedom of desire and “amorous exhaustion” but without being able to completely dispel the memory of the “two full days of lust and hatred” that had gripped the entire village. Maude’s precise word choice conveys the complexity of the characters’ emotions and, once again, the presence of the threat from the villagers. At this moment we understand that Rebeca’s break from the past and her newfound desire is unsustainable: “See things the way they are, not the way we want them to be. They will come, and you will give me to them. I accept my freedom,” she says to her final lover.

Comparisons between Somers’ work and the work of Chilean author María Luisa Bombal have been made because both writers focus on the female experience, their interaction with the natural world and the search for freedom from prescribed roles. Readers who have enjoyed Bombal’s work will enjoy this novel. But Somers’ writing goes even further in exploring the quest for female subjectivity and highlighting the complexity of the reality of freedom of desire and choice for both men and women in a repressive society with strict cultural norms and expectations. In this way, Rebeca Linke’s transgressive behaviour brought to mind the protagonist of Argentine author, Ariana Harwicz’s Die, My Love, released in English in 2017 by new translation publisher, Charco Press. In Die, My Love, a frustrated and isolated new mother assertively and sometimes violently rejects the roles that her husband, family, and society have cast her in and pursues her sexual desires. Rebecca Linke’s short-lived liberation and disruption of accepted ways of living and expressing oneself only serves to demonstrate the complex negotiations and shifts that need to occur to fully allow for this to happen. This is significant today as women still face the difficulty of negotiating these changes when living under repressive cultural or political regimes which limit freedom, in communities where women’s voices are silenced, often through violence, and in workplaces where women’s choices are limited and their progression constantly undermined.

Sophie Stevens is a researcher, translator, and theatre practitioner. She holds a PhD from King’s College London on Uruguayan Theatre and its translation into English and she is currently working on the project, Language Acts and Worldmaking. Her translations of plays into English have been presented in London at CASA Festival at Southwark Playhouse, The Out of the Wings Festival, and The Cervantes Theatre.

*****

Read more reviews on Asymptote blog: