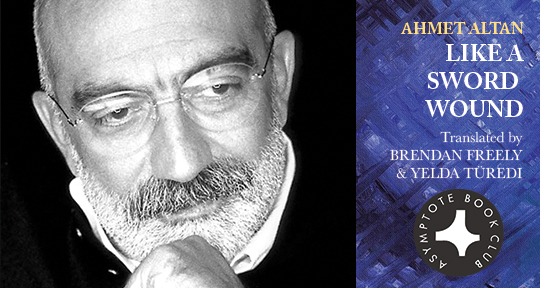

Our October Asymptote Book Club selection is the first novel in a quartet that aims to reveal “the dark and bloody face of history.” Earlier this month, a Turkish court upheld a life sentence for the quartet’s author, Ahmet Altan, on charges of aiding the plotters behind the failed military coup in 2016. He continues to work on the final volume of the quartet from inside his cell. Like a Sword Wound can be read as an autopsy on “the sick man of Europe”, the ailing Ottoman Empire at the turn of the last century, but also as a powerful indictment of despotic regimes across history.

We’re proud to be bringing our subscribers a novel of incredible courage, inspired by a belief that literature is close as we can come to finding “an antidote to the poison of power.”

If you’re already an Asymptote Book Club subscriber, head to our official Facebook group to continue the discussion; if you haven’t joined us yet, Garrett Phelps’ review should give you a brief taste of the novel, and all the information you need in order to subscribe is available on our Book Club site.

Like a Sword Wound by Ahmet Altan, translated from the Turkish by Brendan Freely and Yelda Türedi, Europa Editions, 2018

Reviewed by Garrett Phelps

Published in Turkey in 1997, Like a Sword Wound is the first installment of Ahmet Altan’s four-volume “Ottoman Quartet”, which recounts the Ottoman Empire’s collapse and Atatürk’s rise as an unchallenged visionary of the new Turkey. While too much modern “historical fiction” tends to rely on nostalgia and cheap fireworks, Altan reasserts popular history as one of the novel’s greatest subjects.

The novel is a breathless portrait of late-19th century Istanbul—the corrupt, violent and authoritarian core of a failing empire—as well as a handful of its key actors. Most importantly there’s Hikmet Bey, a prominent clerk to the Sultan, whose swing towards Turkish nationalism, as well as taboo sexuality, threatens his social status and his marriage. He and Mehpare Hanım, his wife and the ex of an influential Sheik, get tangled up in an illegal ménage à trois with their child’s nurse and push marriage roles to a breaking point. Under a regime where love is “fed and raised” on fear, this turns out to be especially dangerous. “In such a climate,” Altan writes, “the souls of the people who contained their emotions in the deepest part of themselves, who were surrounded by prohibitions and religious laws, became pitch black, and their emotions exploded suddenly . . . ” As an axiom, this applies to almost all the novel’s characters. When a political dynasty is on the brink of self-implosion, its population often follows suit.

One of Altan’s gifts as a historical novelist is his ability to connect what goes on, say, in the marriage bed with what occurs on a world-scale. There are no grand gestures of “Great Men” at the expense of everyday experiences. Rather, the commonplace mirrors bigger events or triggers them directly. Something as dull as a broken carriage-wheel can lead to “a chain of disasters, murders that would shake Istanbul, and to thousands of lives being consumed in lonely and impoverished exile; but no one saw the portents of this dark future when the wheel broke.” Very little about this book is grandiose, a rarity for a work of historical fiction. This is an Istanbul full of disappointing sex, sketchy political murders and the kind of codified fear that comes with living day-after-day under a despotic regime. In Altan’s hands, though, it all has a certain dignity. He picks the garbage off the ground and sets it in the sphere of historical interest. Personally, that’s my favorite sort of history.

Garrett Phelps has been an assistant editor with Asymptote since July 2018.

*****

Read more about the Book Club on the Asymptote blog:

- In Conversation: Mui Poopoksakul

- Announcing our September Book Club Selection: Moving Parts by Prabda Yoon

- Announcing our August Book Club Selection: Revenge of the Translator by Brice Matthieussent