Babylon by Yasmina Reza, translated from the French by Linda Asher, Seven Stories Press, 2018

The “soirée entre amis” (literally an evening among friends) is one the most quintessential of French clichés. Quintessential not only for its pervasiveness in art centred in Paris, but also because it is ridiculously pervasive in real life, too. A staple, even, of life in France. And, if like Yasmina Reza, you believe that “you can’t understand who people are outside [their] landscape,” what better setting for the exploration of the pressures and absurdities of daily existence than precisely a dinner party between friends, a space that demands constant performance due to its many spoken and unspoken social rules?

In a fictional suburb of Paris, Elisabeth and her husband, Pierre, are throwing a party for their friends and family. Invited, at the very last minute, are their neighbours the Manoscrivis, Jean Lino, and Lydie. The party goes well, but tragedy strikes shortly after: Elisabeth and Pierre are woken in the middle of the night by Jean Lino, who has killed his wife after a banal domestic dispute. Even more inexplicable is what follows as Elisabeth, a sensible and rather ordinary woman, decides to help Jean Lino get away with the crime, despite sharing nothing more than a tentative friendship.

Babylon, translated from the French by Linda Asher, gives away its story early and belongs to that very popular category of books that use techniques of the thriller and mystery genre in what is essentially a character study. A whydunit, rather than a whodunit, so to speak. In this, it is reminiscent in some ways of Leïla Slimani’s The Perfect Nanny (translated by Sam Taylor), where the reader traces the journey of a woman from perfect nanny to chilling baby killer. In fact, both books were in the running for the 2016 Prix Goncourt, won ultimately by Slïmani. The loss was no tragedy for Reza, who a few weeks earlier had taken home the Goncourt’s “semi-twin,” the Renaudot, for this same book.

But while The Perfect Nanny is a claustrophobic tale of a woman’s unravelling, deeply attached to a very specific social context (an abused middle-aged nanny, overcome by debt and about to be fired), in Babylon, Reza attempts to elevate what her characters experience in their limited domestic sphere to a universal tale about how certain fears unite and drive us toward inexplicable acts. It is this push for universality that makes the novel hypnotic, often poetic, but also uneven.

While populated with more than a dozen characters, Babylon is ultimately the story of two people: Jean Lino and Elisabeth. And the mystery at its centre of its plot is twofold. The reader has to understand both what drove Jean Lino to murder and why Elisabeth tried to help him get away with it. The questions are jarring, because they arise mid-way through the novel, after Reza has given us enough of both of their lives and personalities (through their behaviour at the party or Elisabeth’s own fragmented memories) to set up a contrast. Jean Lino is a mild-mannered musical therapist with a mother whose health is failing and a cat he speaks to in Italian. His wife is a jazz singer moonlighting as an astrologer, or the other way around, depending on the day. Elisabeth, too, is far from extraordinary. A happily-married researcher, with a nice house in the suburbs and a grown son who has no more space for her in his life.

The question Reza raises through Babylon is how are ordinary people pushed to inconceivable acts of violence (in Jean Lino’s case) and stupidity (in Elisabeth’s). The answer seems to lie in the nature of ordinary life itself. In social interactions, Reza reminds us, there is lot that is performative, quite a bit that relies on our shared knowledge of each other. They tend to reinforce our image of who we think we are and where we stand socially. But at times, these same ordinary settings can surprise us, something unexpected happens and a crack opens, showing us other possibilities: who could have been, had things been different. And these cracks undermine our carefully built identities, throwing us off balance, making us commit random acts of absurdity.

And while Elisabeth is the narrator, it is Jean Lino’s side of the story that illustrates this principle better, the way small changes in our landscape and surroundings can shake and overturn our sense of self. Jean Lino is Lydie’s second husband and struggles to find his place in her complicated family dynamic, trying his best to gain the love and respect of Lydie’s nephew, Rémi. A quiet soul, he has never been the centre of attention, nor felt particularly loved by anyone. During this party, to which he was invited out of courtesy rather than desire, he moves from the margins to the centre of attention through an accidental joke:

Anyhow he couldn’t say anything for sure on the matter, the only Italian he spoke was with his cat, and they never discussed politics. This charmed the crowd and he inadvertently became a pet of the evening.

As Reza astutely observes, however, the rush that is felt upon this ordinary success is never enough. For the first time, perhaps, Jean Lino is the center of attention and even affection, so he pushes beyond his timidity, trying to earn more of this laughter that is precious currency in the setting of a social evening among friends. Except that the more he drinks, the more his jokes turn to the humiliation of his wife Lydie, little jabs at her interest in astrology and animal rights, that turn Lydie against him. Lydie’s displeasure in turn is not only at this spontaneous humiliation, but also because the balance of the relationship is broken: she is usually the one in control, with Jean Lino trying to join into from the margins.

But after the party is over, Jean Lino and Lydie return to their upstairs apartment, to their usual landscape. Here, Lydie tries to reinstitute the balance, reminding Jean Lino how pathetic, how obvious his attempts at being someone who he is not (interesting, the life of the party, confident). How, like her nephew Rémi, these strangers could see through his attempts to please, to be loved. With her words, Lydie holds a mirror to Jean Lino’s true self, a mirror distorted by her perception as much as his, but a mirror nonetheless. And this reflection of distorted truth is unbearable. And it is this moment of recognition that is transformed into violence, literally silencing (through strangulation) this agonizing voice of truth.

Domestic violence, for all its psychological underpinnings, is not foreign to the readers. What truly baffles are Elisabeth’s stubborn attempts to help Jean Lino get away with murder. While both Pierre and Elisabeth are notified by Jean Lino of his crime, Elisabeth is the only one who goes back to Jean Lino’s apartment, in her pyjamas, lends him her oversized suitcase, helps Jean Lino stuff his dead wife inside and then, still in her slippers and pyjamas, proceeds to help him carry the suitcase to his car and to his wife’s office, where they hope to stage a natural death. And it is in this perspective that the novel loses some of its power. It is unclear whether Reza is consciously trying to warn us against Elisabeth’s predilection to romanticize the past, or rather is using it as a tool to remind us that youth, and life in general, are fleeting. To what extent then, is Elisabeth a foil for the author herself?

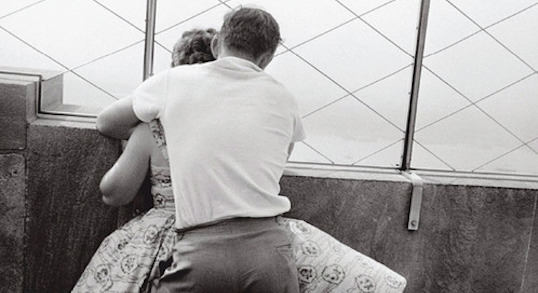

What remains is that what are perhaps banal reasons for Elisabeth’s temporary vacillation in sanity are hidden behind poetic language that betrays a penchant for both melancholy and melodrama. Interspersed between scenes of the party and the ensuing crime are Elisabeth’s memories of bygone youth, a sense of profound loss captured through pensive one-liners. “We were young. We didn’t know it was irretrievable,” she says of the nights spent with friends. Whereas in the present, Elisabeth is shaken by the fact that she felt she “belonged to that throng moving along, hand in hand, growing old, moving along towards something unknown.”

But it is important not to get so easily lost in the poetry of nostalgia. Elisabeth’s actions are a reaction to the fear of getting old and the realization that these parties are as exciting as it gets. That her life is set. This sentiment is betrayed when Elisabeth faces her divorced younger sister, now in a BDSM relationship with a farmer. Faced with her sister’s risqué lifestyle and a behaviour idiosyncratic to who they had been brought up to become, Elisabeth wonders:

I thought, So how come no tattooed guy with a whip turns up in my life? I felt finished, out of the game, fit for putting together little suburban parties with family and ultra-conventional folks. I’m irritated with myself for thinking that way. I’m happy with my husband.

Behind the veneer of words are motivations as banal as any other person’s. If she helped Jean Reno, it is because for the first time Elisabeth was becoming part of something exciting, out of the ordinary. The uncertainty of being caught, of perhaps ending up in prison with Jean Reno, of not belonging to the same landscape she had spent more than thirty years fitting into.

Yasmina Reza has gained fame, both in France and the United States, as a screenwriter. Her plays have won her multiple awards, including two Tony Awards: the first in 1998 for Art and in 2009 for God of Carnage, both translated into English by Christopher Hampton. Most of Babylon will feel familiar to Reza’s fans, who in her earlier works is again interested in how ordinary acts of living betray the absurdity of life itself. And perhaps because of her career in theatre, there is much in this novel that feels like a play, scenes that would be funnier if seen rather than read: Elisabeth in her pyjamas, Jean Lino in his dishevelled clothes with a massive red suitcase, trying to drag it through the claustrophobic hallways of Parisian buildings. While the novel allows her to explore Elisabeth’s state of mind, her constant reminder that her youth is now gone, often this same introspection feel superfluous when compared to how, for instance, Jean Lino’s storyline manages to capture so much of his perspective through the domestic interplay alone.

And, in the end, it is again not Elisabeth’s introspection that provides the best coda for this text. Rather, the words of Etienne Dienesmann, a secondary character and colleague to Elisabeth, are the ones that better summarize Babylon’s and Elisabeth’s fears and aspirations: “Every summer, surrounded by laughter, he felt his own unimportance. Eventually he came to experience it without bitterness.” By the end of Babylon, and her ordeal with Jean Lino’s crime, it seems Elisabeth too is ready to experience her own ordinariness without bitterness, upon realizing that excitements at her age are better in theory.

Barbara Halla is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Albania. Originally from Tirana, she currently resides in Paris where she works as a freelance editor and translator for French, Italian, and Albanian. She holds a BA in History from Harvard.

*****

Read more about French literature from the Asymptote blog: