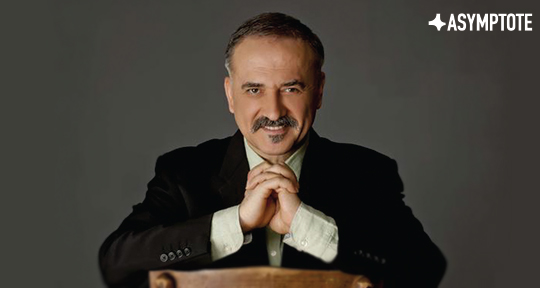

Murathan Mungan likes to describe himself as a polygamous writer: not only does he write plays performed across Turkey and Europe, including his widely acclaimed trilogy, The Mesopotamian Trilogy; he also writes essays, song lyrics, poetry, and novels that have brought him national recognition as one of the most inventive Turkish authors for the use he makes of the Turkish language. Being himself of mixed origins (Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish and Bosnian), he is very sensitive to the life of underrepresented groups such as women, Kurds, the LGBTQI+ community, and explores taboo themes in his creative writing. I interviewed Mungan in the Czech Republic in the Month of Authors’ Reading Festival where the guest country was Turkey. His latest works include a novel called The Poet’s Novel and a play, The Kitchen. He is currently working on a novel describing the urban aloofness of Berlin.

Filip Noubel (FN): Murathan, you embody a plurality of personal origins, and seem to favor characters from various minorities. Why is diversity essential in your life and in your work? And how is it perceived in Turkey?

Murathan Mungan (MM): Many people live inside of me. I come from the city of Mardin, in the southeast of Turkey, a city close to Syria and not too far from Iraq. Mardin mirrored the diversity of my own family: my father’s ancestors came to Turkey in the 17th century from Syria, my paternal grandmother’s mother came from the Kurdish regions; my mother’s side is from Sarajevo, which is in Bosnia today. Though I was born in Istanbul, I grew up in Mardin and within a mix of cultures and religions, mingling with people who are Turks and Kurds, but also Assyrians, Alawites, Yezidis, and Armenians.

In Turkey, the main issue with diversity is about naming: people turn a blind eye to the identities of minorities as long as they don’t name their identities publicly. But once the naming of identity happens, it becomes no longer acceptable to display it. I can give you two examples: in the heydays of the Turkish film industry—the Yeşilçam period of the 1950s to the 1970s— many people working on the technical side of the industry, such as set designers and sound engineers, happened to be Greeks or Armenians, and had their original names mentioned in the film credits. Yet actors and actresses, the ones who appeared on the screen, the ones who had their faces up there, would use Turkish names and surnames. As long as the minorities lived invisibly, everything was okay, today, the same goes for gays. People tolerate them as long as they are not open about their identity. Indeed many gay men will vehemently deny that they are homosexual while speaking in public.

Today, one of the main problems in Turkey is that the mass feeds on grudges and hate in a worsening fashion. In order to maintain the polarization promoted by the government, internal and external enemies are considered something necessary. It thus needs an internal enemy to feed such attitudes, and the usual targets are, as always, various minorities. I have to say our current time is the worst period I have experienced in my life so far. At the same time, Turkish society is rather irrational, where what is forbidden, and what is allowed, change constantly. I am the first writer in Turkey to come out of the closet, I don’t hide myself. The fact that I am a cultural figure, the fact that I am accepted as a writer may be protecting me to a certain extent, but it doesn’t mean that nothing will ever happen to me.

FN: In one of your short stories, “The Hidden Me,” you write: “I’ve been searching for myself on that empty page for many years. On how many pages have I appeared and disappeared.” What is the drive that pushes you to be such a prolific author in so many genres?

MM: I often say that I am a polygamous writer: I write poetry and plays, novels and short stories, essays and song lyrics. As I write in parallel, one project catches my attention, and then I drop everything else and focus on what becomes essential.

FN: It seems there is one standard question among non-Turks about Turkish literature: is it looking East or West? Do you think this question is relevant? Why do you think they keep asking this?

MM: Let me give you a typical example. I recently submitted my novel to a major German publisher. The novel takes place on another planet, it is a fantasy piece, a dystopia. The publisher wrote back after some time, saying: “We loved your novel very much but this is not a novel that a German reader expects from a Turkish writer.” And I responded: “If you really liked it, publish it under a pen name like Robert Smith, I won’t object!” Biting irony yet deep truth!

I always thought the most difficult thing in life was finding a loved one, as it turns out, it was actually finding a good translator!

FN: You are currently residing in Berlin, and writing a novel about that city. Germany and Turkey are linked due to a long history of political alliance and migration. As a result, a group of writers, who to some extent belong to, or find inspiration in both cultures, has contributed to the Turkish literature. Do you consider yourself part of this global Turkish literature? How do you think this experience can enrich writers back in Turkey?

MM: I actually had an interesting experience in Berlin where I moved recently for a six-month residency. I am currently writing the third part of a large trilogy – and Berlin becomes what I call the ‘sıfır kilometr’ – or Kilometer Zero, as I describe the lives of people who are lost in Berlin, and focus on two main characters who remain nameless. I got inspired by that cautionary announcement in the U-bahn –the Berlin metro: “Zurück bleiben bitte!” This phrase literally means ‘stay back’ and indeed echoes the lives of people who are in Berlin but come from other places and stay in the back of German society.

Photo Credit to Muhsin Akgün

Petra Sedmíková and Ilker Hepkaner helped Filip Noubel with the translation of the interview.

Filip Noubel is a literary translator and critic based in Prague. He studied Slavonic and East Asian languages in Tokyo, Prague, Paris, and Beijing, and has worked as a media trainer in Central Asia and China. He now focuses on contemporary fiction from China, Uzbekistan, Russia, and the Czech Republic, which he translates into French. His translations and reviews have appeared in Jentayu Magazine and in 单读/Dandu Magazine. He is currently translating Radka Denemarková, one of the most awarded contemporary Czech authors, who has also been featured in Asymptote.

*****

Read more about Turkish literature from the Asymptote blog: