Selling books can be a form of political activism. That’s according to Ketty Valêncio, who founded the initiative Livraria Africanidades, a unique bookstore in São Paulo that only sells books that focus on and valorize black women.

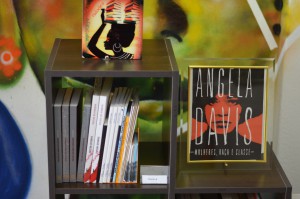

Africanidades Bookstore began online in 2014 and opened its physical location in December 2017. The walls of its new home have murals created by black women artists and its bookshelves are lined with fiction, poetry, feminist theory, nonfiction, and even cookbooks, the vast majority of which are written by black authors from Brazil’s peripheries. The space carries the fruitful results and future promise of selling books by authors who reside on the margins of the Brazilian publishing scene—or who are excluded entirely from the traditional literary market.

Here, Ketty Valêncio tells Asymptote Editor-at-Large in Brazil, Lara Norgaard, some of the challenges for women of color in Brazilian publishing and the power of increasing visibility for writers of color, both in Portuguese and in translation.

Lara Norgaard (LN): How did you come up with the idea for the Africanidades Bookstore?

Ketty Valêncio (KV): The bookstore came about because of my struggle to understand myself as a black woman. I never felt that I fit in anywhere. And then I came across Afro-Brazilian literature, texts that have black characters as protagonists. I understood my blackness through literature, through these books written by black authors and also by a few white authors who place value on black characters. I came across these narratives and thought, wow, there are people writing about me, about who came before me, about my ancestors and my memories.

I studied library science and also didn’t fit in. The literature that pervades the field is that of white, heterosexual men. Once I graduated, I realized how little most people know about black literature. When I had the idea for the bookstore, I decided to get an MBA in order to handle the bureaucratic, business side of things. Once I finished that degree, I put what I had learned into practice. With a bit of courage, I started the website.

Throughout the process of starting the bookstore, I learned about myself, both as a physical person and as a micro-entrepreneur, and about how people respond to the texts I sell. The project continued to grow and I took part in book shows and events. I’m a sort of cultural ambassador. Even though there’s a more commercial side of things, this work is cultural activism. I introduce an author to readers and talk about the story behind their books. Or, when people already know the texts, it becomes a collaborative kind of work, one in which people add their ideas.

LN: What was the transition from an online bookstore to a physical location like? How did the project change?

KV: It’s different, even though I still keep up the website. The physical space brings about another kind of identity for the bookstore, one that exists in the public sphere. I try to have a cycle of events rather than just sell books. Even though books are sold as objects, you can add value to those objects. That’s the new objective of the physical space.

It’s expensive to have space in São Paulo. I’m privileged, in that sense, and so the idea is also to keep hosting new people and new ideas, to keep adding to what I’m doing, and even to expand.

Being a black business owner in Brazil is hard. I think it’s fairly easy to open a store, but not to maintain one. The question of making a living in the market is tricky, especially in bookselling. The industry works sort of like a wave, and you have to stay above water. You don’t swim, you just try to float so as not to be swallowed up and destroyed completely. I think I’ve survived because of my political vision. If I’d done something more business-oriented, I don’t know if I’d be here talking to you right now. I would be buried in my entrepreneurial grave.

The activism of this bookstore is collective. People helped and continue to help me build this. People also expect something from me, especially the authors. When I sell their books, they’re betting on me. I end up mediating the interaction between author and reader. The books I sell come from a range of a small, medium, and major publishers, but some don’t have the stamp of an editor’s approval. The authors work on their own, putting their books in their backpacks to distribute them. I’m there, in the middle of that difficult path. It’s their art, and they believe in me. That’s a huge responsibility.

LN: You mentioned the challenges of being a black business owner, and it’s also clearly very difficult for black women to be published by mainstream publishers. What do you think are the greatest challenges for black women writers in Brazil?

KV: I think it’s the very question of speech. A woman’s words are not trusted simply because it is a woman that spoke them. Her narrative always has to prove itself. A woman, especially a black woman, has to prove herself to be capable, efficient, and judicious.

Men dominate the literary world and publishing industry. That has always been the case. In schools, students don’t study very many women, and even fewer black women. They aren’t included in basic education here. And then, to enter the literary market, the academy has to endorse them. If you look at who is in the literary academy, you’ll find that very few women have a seat at the table. When they do, they’re white, upper-middle class women.

Black women in Brazil mainly exist outside of academia. They have an entirely different trajectory. Most are legitimized in the periphery. They come from the effervescence of periphery cultural centers and events. They might end up getting read online, if they have a blog or a YouTube channel. Or they might take part in zines, which have helped a lot in the proliferation of ideas.

All of this ties into the sexism and racism that manifests itself in the literary world. Take the example of Carolina Maria de Jesus, who is an absolutely pioneering author, one of the central figures of black Brazilian literature. Her work has to be proven worthy to this day because she was a woman. People still question if she wrote well. Literature professors ignore her. The same goes for contemporary female writers, like Conceição Evaristo, who is a highly regarded, legitimized, marvelous author, and yet still few people know who she is. She has said that she wants to be the rule, not the exception. Right now, she’s the exception.

It’s also not a coincidence that women don’t rise to the top, since they don’t appear in the media, either. Women can’t get any visibility. And the thing is, when a black girl sees a black female author, she thinks, I’m similar to her, my way of life is similar to hers, and that leads to the idea that she too can be a writer. That can change a girl’s entire world. The place that was socially determined for her doesn’t have to be her place anymore. Teaching someone that she can be anything she wants to be is revolutionary, and that’s why what I do is activism. It’s a political tool that deals with the question of places of superiority and inferiority, building a bridge across the gap between social classes that widens each day.

LN: Considering that many of these authors started publishing online in some way, through blogs or YouTube channels, do you think the internet democratizes Brazilian literature?

KV: I think so. But at the same time, it’s not all-inclusive. A lot of people in Brazil unfortunately still don’t have access to the internet. But the internet allows women to share their writing, and so there’s greater visibility regardless.

When you officially publish a book, editors decide if they want to publish it or not. A lot of these narratives are very painful for women to write. It’s not easy to put something on paper and then wait for people to read and evaluate you. An editor also changes the text to sell it, to make it a popular product. That’s not necessarily bad, but it means you have to put yourself into a category. That doesn’t happen online. People might express their opinion, positive or negative, but they will read your writing regardless.

At the same time, there’s a lot of hate. You can be racist, chauvinist, and display your hatred without regulation online. Sometimes people who think that way wouldn’t display those opinions in the real world, but they do on the internet.

LN: How do you choose which books to sell in the bookstore, considering both the market and your own activism?

KV: It’s very personal. The personal is political, and that applies to this bookstore. As other spaces validate white men, my bookstore takes the opposite approach. I consider different questions as I read. There are good books here that I’ve already read, thinking, I need to sell this so that people can discover it. It affected me. Then the author’s story is also important to me. It has to connect to the work in some way.

There are white authors here, too. They’re a minority, but they are authors who at least do the important work of building and placing value on black characters. Or they put value on women, which is also important. I like to say that the bookstore is a place of memories and voices, all building some kind of truth.

LN: It also looks like you sell authors both from within Brazil and abroad.

KV: Yes. I have authors from Brazil, many from São Paulo, and then I also try to bring in narratives from other states. There’s a focus on the southeast of Brazil, and I’m trying to break away from that too. Everything comes from Rio and São Paulo, and sometimes from other states in the south, but literature from other states in the north and northeast isn’t visible. I don’t have everything here, but I’ve accessed some.

Beyond Brazil, I have a few books from the African continent and a few from the United States. I’m trying to add more. Those are other lines of thinking, different points of view, but at the same time it all intersects because the starting point of our diaspora is similar. The collection ends up a fragmented montage of memories, of the histories of violence that we are obligated to belong to.

LN: The range of Brazilian authors that English-language readers have access to is very limited. It’s difficult to find many black women Brazilian authors in an English translation, and it’s even more difficult to find the regional diversity that you just described. Is there an author here in the bookstore that has been translated to English who you would recommend to readers abroad?

KV: Most of the authors whose work I sell have not been translated. Often, they aren’t widely popular, they don’t have much interest in the market, and the market doesn’t have interest in them, unfortunately. But one author who has been translated into English is Carolina Maria de Jesus. I think she’s one of Brazil’s best authors.

LN: Is there a book you wish existed in translation?

KV: Yes, many. Miriam Alves is a formidable author, part of the old guard of black literature in Brazil. She taught me a lot about the mythology surrounding orixás, gods in the Afro-Brazilian religion candomblé, which is at the core of our existence, of the history of the African continent, and of our current reality. It’s a question of diaspora. Miriam is an extremely interesting woman who is also a poet and takes part in some slams and cultural events here in São Paulo. I think books of hers such as Bará—na trilha do vento (Bará—on the Wind’s Path) would be wonderful in translation.

There are a variety of other authors as well, particularly poets. Poetry has a certain kind of sensitivity, an emotional tenor, and when you take it to another language you also end up understanding the specific structure of society, in a way. There’s a collection of poetry, Pretextos de Mulheres Negras (Black Women’s Subtexts) organized by Carmen Faustino and Elizandra Souza, which was printed with graphic design also done black women.

This interview was translated from the Portuguese and was edited and condensed for clarity.

Lara Norgaard is a recent graduate of Princeton University in Comparative Literature with a focus on Latin America. She teaches English and researches public memory in Brazilian literature as a 2017-2018 Fulbright Scholar in Brazil.

*****

Read more interviews from the Asymptote blog: