It was during the summer of 2015, as I was doing research at the National Library in Singapore, that a small sheaf of papers fell—quite literally—into my lap. Covered in dense 1970s newsprint, I was about to place it back on the shelf when some handwritten Vietnamese at the top of a page caught my eye.

Trại tỵ nạn Hawkins: kiểu mẫu của sự hòa hợp, it read, accompanied by a translation: “The Hawkins Road Refugee Camp: A model of harmony.” I was intrigued. I had heard, of course, that “boat people” had arrived in Singapore after Vietnam’s reunification and subsequent invasion of Cambodia. I had heard, too, that most were turned away by the Singapore Navy after being provided with fuel and water, in a controversial exercise that came to be known as Operation Thunderstorm.

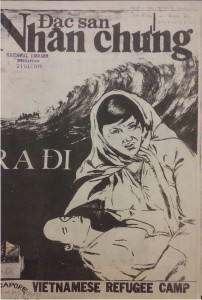

But nobody had told me—not in school history lessons, nor in conversations with my peers about the recent and ongoing flight of Rohingya from Myanmar, and what we could do—that Singapore had (albeit reluctantly) also provided temporary asylum in the 1970s to thousands of refugees, in facilities set up by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Nor that the first refugees to come ashore in independent Singapore had founded, translated, and produced their own literary journal, Nhân Chứng (Witness), full of harrowing stories alongside photographs, songs, and poems.

For the next hour, my honours thesis sat unwritten on the desk as I turned the fragile pages. What I read stayed with me as I returned to the UK and threw myself into readings and discussions in the run-up to Brexit, making the case—with other “minority” poets—for a more open Britain. And as I began writing about my own region’s stories of exile and refuge, the words of these refugees from three decades ago found new resonance with the voices of Rohingya and other asylum-seekers in the present.

Like me, many Singaporeans had no idea before 2015 that the country had once hosted a refugee camp, and for nearly two decades. My parents, who were teenagers then, remember little; most others whom I’ve spoken to recall vaguely where it was established, but not when, or for how long.

Then, as now, Singapore’s position was hostile. Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam criticized Vietnam for expelling “unwanted citizens” in “floating coffins,” arguing that mass expulsion was a ploy to further Communism in Southeast Asia. “Each junkload of [refugees] sent to our shores,” he warned, “is a bomb sent to destabilize, disrupt, and cause turmoil.” As historian Ang Cheng Guan records, Singapore’s “hard-hearted” policy was to disembark only the asylum-seekers who were picked up at sea by commercial vessels, and only if they came with guarantees of resettlement by other countries.

It was these asylum-seekers, allowed on shore for a “transit” period of three months, who were held in the UNHCR camp at Hawkins Road. Though hardly a trace of their presence remains—the camp has long since been demolished—the journal they published affords latter-day readers, like us, a glimpse into the lives of the 32,457 refugees who passed through Singapore, and received shelter here.

The launch of Nhân Chứng in September 1979 gained some press attention, though unsurprisingly The Straits Times, the main state-sponsored paper, remained silent. New Nation (a now-defunct afternoon broadsheet) called it the “Boat People’s Horror Mag” and carried an image of the journal’s cover, which showed a woman cradling a body, and waves swallowing a ship in the background. In the reporter’s words, it held “horrific tales of escape,” with “each story as pathetic and poignant as the next.”

What stood out as I read the issue cover to cover, however, was less the severity of the refugees’ plight than the moral clarity with which they articulated loss and gratitude, and the quiet lyricism of each contributor’s tale or tribute. “We did not know where we would go, where we would be accepted as individuals, [or] where we would be protected,” wrote Ha Van Ky, who would later edit the journal’s second issue. “Let us live . . . we want to speak up on behalf of human beings.”

Along with the refugees’ stories and interviews were several love poems, addressed to those left behind and others met along the way. For Ngo Ngoc Lam, the country he had escaped was as a “motherland” in more than one sense: it was a place rich with “the love of [its] people,” but also where his wife had “stayed back / . . . [to] look after the children.” Another poem, addressed to a new sweetheart—but one suspects, also a dearly-missed country—began with an anguished cry (“Oh Vietnamese girl who suffers since your birth…”), and ended with an equally heartbreaking promise (“Though our motherland has to endure countless hardships / I’ll try to find worthy gifts to offer you”).

It’s impossible to convey even half of what the refugees must have thought and felt as they penned these lines, all of whom were less than three months into a long, indefinite exile, and often unsure of their next port-of-call. In the journal, their names are all followed in parentheses by the name of the ships that rescued them (Canadian Highways, Emma Maerst, Savonita, etc.), lending us a clue as to how they saw themselves and found community in the temporary and traumatic space of the camp.

What is startlingly clear from these pages, though, is the humanity with which the refugees were received, by camp volunteers if not the state authorities. One contributor to the journal was Sigga Hafstad from Iceland, a teacher at the camp’s language school, who pleaded with readers not to consider the “refugee problem” only as an abstract geopolitical issue, but as “a very acute and well-defined personal problem” for each individual refugee. (Separate accounts by former students report that volunteers like her taught various languages at the school unpaid, from 10am to 10pm daily.)

As it turned out, Hafstad was also the subject of an adoring poem elsewhere in the issue. “She talks wonderful things about the world,” the poet mused, “teaching languages / she brings happiness into us.” Several other staff, local and international, were similarly named and thanked. “We refugees,” wrote camp leader Nguyen Duy Tien in his foreword, “[will] never forget our benefactors.”

With the support of the UNHCR, and the combined efforts of the camp’s photographers, translators, and writers, the first issue of Nhân Chứng was a runaway success. New Nation reported a print run of ten thousand copies, far exceeding the camp’s population of around nine hundred. It was perhaps due to this unexpected reach, though, that the journal caught the attention (and disapproval) of the Singapore authorities. While a second issue was scheduled for release in December 1979, the Ministry of Culture only approved it for publication in February, by which time only three of its eighteen contributors were still in the camp. The others had reached the end of their three-month grace period and were resettled elsewhere.

Obviously, these were disappointing developments. As editor Ha Van Ky put it, “the magazine was [only] meant for circulation within the camp, and to benefactors and embassies, [so] we were not aware that we needed to submit a proof to the ministry for approval.” At the same time, the journal lacked a stable source of funding: each issue cost $6 to print, but was sold to the camp’s residents at only $3. It is hard to imagine how the UNHCR, already stretched thin in the region, could have covered the shortfall. For these and other reasons, the second issue saw a print run of only five hundred. I was unable to find copies of this issue in the National Library and, as far as I know, there are no records of a third.

With the present crisis in Rakhine, and the violent displacement of the Rohingya, countries across Southeast Asia have once again been confronted with questions of exile and refuge. In the absence of overriding Cold War imperatives, and facing a rise in anti-globalist popular sentiment, the Singapore government has refused even to consider the prospect of temporary asylum, citing space and resource constraints to justify its stance. This official position is, unfortunately, also a popular one.

Ironically, there have been several reports in recent months of former refugees, who spent brief periods at the Hawkins Road Camp, returning to trace lost memories or reconnect with those who had helped them during their flight from Vietnam. One of them, Ms. Yen Siow, had these words for her onetime rescuer: “You stopped in the midst of your travels to help strangers who you had no connection with. And today, I’m alive. And my family’s alive. My children are alive.”

Together with the memories of these former refugees, the stories in Nhân Chứng remind us of the possibilities of welcome in a city-state that now portrays its hostility as inevitable, a function of geographical truth. And as all our most important stories do, they also remind us that our collective choices—however inconvenient at the time, or insignificant they may seem later—can mean the world to others in real, lasting terms. That, alone, is worth the telling.

Cover photo credit: Flickr user manhhai.

Theophilus Kwek’s poems, essays and translations have been published in The Guardian, The Philosophical Salon, The London Magazine, and the Asia Literary Review. He serves as Editor of Oxford Poetry, and recently won the Berfrois Poetry Prize. He is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Singapore.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: