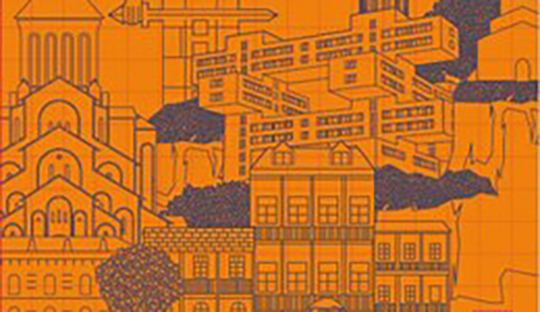

The Book of Tbilisi, edited by Becca Parkinson and Gvantsa Jobava, Comma Press

The Tbilisi funicular that leads all the way to the Mtatsminda Mountain, one that families might usually take on Sunday mornings or lovers for an afternoon date, gives an opportunity to get a glimpse of the city from above while still being close and immersed in the noises and lives it encapsulates. The Book of Tbilisi attempts to be an extension thereof, unravelling to the readers the literary landscape of Georgia after the recuperation of its independence and the consequent transformations it underwent. Comma Press’s “Reading the City” series brings to the surface works and literary traditions of underrepresented areas. This endeavour aspires to insert forsaken voices and cosmologies into the Eurocentric literary canon.

One should not overlook the genre chosen for this aspiration. An underrated form that has experienced a renaissance in recent years (as could be attested by Asymptote’s Winter 2018 Issue special feature on microfiction and the 2013 Nobel Prize awarded to Alice Munro), the short story is distanced from illusions of coherency and authority. Instead, its fragments embrace the gaps and absences, charged with an energy that surpasses the mere focus on the sequence of events, in order to capture a state or a quality. Thus it is not difficult to imagine why this impressionistic genre seemed the adequate vehicle—much like the funicular itself—to capture the fleeting force that runs through Georgia.

With a maelstrom of words, the journey begins in the rough yet intriguing literary life of contemporary Georgia: “Journalists were like cigarette ash and the news desk was like a dirty ashtray that no one bothered to empty till it was full” (1). Dato Kardava’s “Uncle Evgeni’s Game” (trans. by Nino Kiguradze) instantly captures our attention with its fragmentary structure, shaped by recorded extracts that polyphonically disclose the obscure genealogy of a murder. A young journalist in search of an intriguing story unveils a forgotten murder. The alleged murderer was found in the hospital with “part of his intestines […] out” (3), accused of killing his family. As the journalist moves deeper into the stories and lives, he attests that nothing is proven and no one can be completely sure about the truth, as the testimonies contradict each other, and the author lucidly reminds us that “life is a game” (18).

The smoky air of a newspaper’s office gives way to a lazy Sunday morning. In Gela Chkvanava’s “On Facebook” (trans. by Tamar Japaridze), we find remnants of the old brutalist blocks, where time bends and the mundane whirls and overflows, culminating in a transient spectrum of community. A childish declaration of love in yellow chalk, “ANZOR+THEA=LOVE,” is enough to trigger flickering screens, gossip and thoughts that encapsulate the motley lives of a nine-story building. Neighbours eager to find “Thea” plunge into Facebook profiles and chat with each other. Idleness and curiosity intermingle with the ingression of social media in everyday life in order to agitate the concrete greyness of a forgotten community. “You wouldn’t notice anything unusual about our apartment building, just by looking at it, but I can feel it buzzing and humming like a beehive” (27).

In a similar vein but with different echoes, Zviad Kvaratskhelia’s “Peridé” (translated by Mary Childs) begins: “I jump up, throw back the curtains and all is well” (49). Partially narrated by a middle-aged lady, Peridé, going out for her exercise routine, a string of memories unveils little details from her first appearance in the neighbourhood—her tutoring, her quarrels—before they merge with the day’s mundane trivialities, such as the Kurdish girl bargaining her goods, the queues and childish promises that changed Peridé. There is no need for cardinal events to transform a person; it is the insignificant moments, the waiting at the queue, the small talk, and the early morning thoughts that can gradually and imperceptibly spark the metamorphosis. And it is the same moments, the same humdrum that fleetingly makes things clear.

Iva Pezuashvili’s “Tsa” (trans. by Mary Childs) contains darker nuances and a more explicitly critical stance towards the current social conditions in Georgia, distanced from old-fashioned truisms. “Life is a strange compromise. There are so many issues to address, so many things that need saying, or need writing about” (64). Three Chinese women that used to work for a circus in the suburbs of Beijing have arrived in Tbilisi. The main character, enchanted by the beauty of the Chinese girl with the long black hair and her elegant tightrope walking, invites her to the talent show in which he is working. As her number attracts more attention, the media’s degradation and the distorted notions of national purity and xenophobia come in contrast with the delicate, startling and incomprehensible artistic skills of the Chinese girl. Intimate, disturbing and exquisite, “Tsa” unveils the harsh face of a community.

The vibrant sarcasm of “Tsa” becomes deafening in Shota Iatashvili’s “Flood” (trans. by George Siharulidze). Baffling, mystifying, disconnected and inconclusive, it progressively creates its own logic and meaning out of the chaos, documenting a mental breakdown of a family that “suddenly decided to destroy the house” (85). There is no plot to be followed but the spasmodic movements of the characters that impel us to wander around indifferently with them, stepping on what used to be their warm wooden floor, with teddy bears qua religious icons listening to their prayers and watching a family playing, singing, smashing, crying, drowning, smiling.

The paranoia of the omnipotent and omnipresent power of the State becomes even more explicit in Erekle Deisadze’s “Precision” (trans. by Philip Price), where the Kafkaesque irrationality of governmental procedures interrupts the life of two siblings in a train carriage that was to become a living mausoleum. “Without the slightest trace of emotion […]. The state loves precision” (45); violent numbers and measurements veiled as philanthropic aid, insensitive to life, sickness and care, frame the story of Tusi and her brother encountering cancer, love, homelessness and the government’s faithfulness to protocols and numbers.

A quite different picture of a family is contained in Rusudan Rukhadze’s “Dad after Mum” (trans. by Tamar Japaridze). “Every morning I hoped he would kiss me on the forehead with the words: ‘Don’t be silly, Sallie! How could a father not recognize his daughter?” (93). After her mother’s death, Sallie’s father lost his memory, forgetting his pain for his lost love, his daughter, the beach walks and the name games. Sallie is still close to her father physically, taking care of him. Nevertheless, he stays almost silent, not able to recall who the person standing in front of him is. The little, insignificant words her dad mumbled before, are now her most precious memories and her only resources in her attempt to transform a blank face into her father again.

Life in absence, existence ex-nihilo, antiseptic in the air, “care” dressed up in white uniforms and stereotypical procedures, dying in clearly prefigured steps and doses: I. Archuashvili disturbs this image in “Balba-Tso,” translated by Philip Price. “Balba-Tso” is written with the ink of Irina’s thoughts, who was diagnosed with a tumour and now recounts: “piece by piece, drop by drop, I leave behind my flesh and blood, entrusting them to men and women in white coats” (119). Her dreams and affective memories splash onto the clean, uncontaminated walls of hospitals and oncological centres, infecting the procedures that crystallise people into patients, earth into cement, dreams into pills.

In a more light-hearted prose, Lado Kilasonia, (trans. by Maya Kiasashvili), carves and sculpts stereotypes to tell the story of a schoolboy hooligan. A group of teenagers, headed by Zuriko, embodies the attitudes and the character of a Bronx gangster and tries to terrorise their classmate. An attempt to prove one’s courage and power goes wrong, proving that we are not always the stars of a story.

Bacho Kvirtia’s “Patagonia” (trans. by Nino Kiguradze) is a compelling end to this collection. We follow Vero, a former geography teacher and current street vendor of bread. Her thoughts and memories lead her back to her migration to Turkey and then back to Tbilisi, only to be exploited and used. We learn about her lost son, her abuser, and her warm bread, in a street where “people are walking up and down. Woman, child, student, merchant, homeless, vagabond, prostitute, drunkard, stray dog, police man, soldier… some are leaving, others are returning” (136).

The funicular journey from Chonkadze street to Mtatsminda takes around six minutes. There is no time to process the whole city, only to grasp a momentary sensation thereof. The Kartlis Deda monument watches over her capital, free and inclusive, waiting to gift her guest with wine. The Book of Tbilisi is a work that might endeavour to achieve the unattainable, but as the genre of short stories included therein, it radiates a sentiment, an ephemeral affect, a spark, that is more than enough to germinate something new.

Giorgos Kassiteridis is a Marketing Manager at Asymptote and a translator. He collaborates with various publications writing essays and reviews. With a background in Linguistics and Cultural Studies, his writings focus on issues around language, translation, and digital technologies.

*****

Read more reviews here: