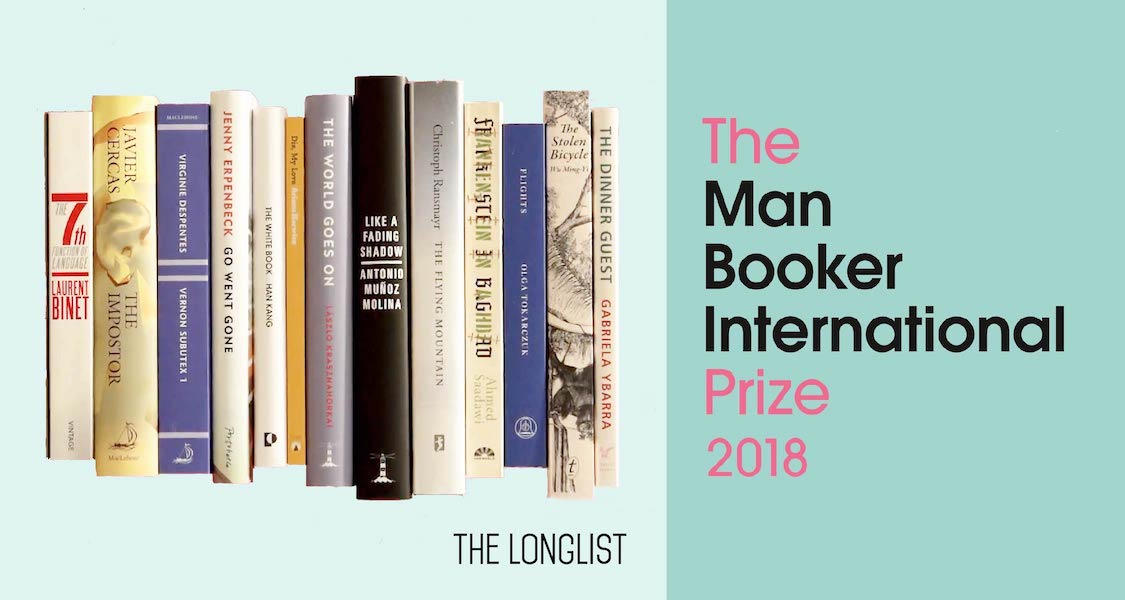

The 2018 Oscars may be over, but the awards season for the literary world has barely begun, with the Man Booker International Prize receiving the most international attention. In the world of translated fiction, the Man Booker International holds a prestige similar to the Oscars, which explains the pomp and excitement surrounding the announcement of this year’s longlist, made public March 12. The longlist includes thirteen books from ten countries in eight languages, from Argentina to Taiwan.

The MBI used to be a career-prize akin to the Nobel, awarded to a non-British author for his or her entire body of work every two years. Since its merger with the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize its format has changed. Now the Prize seeks to honor the author and translator of the best book (“in the opinion of the judges”) translated into English and published in the UK for the eligible period. For 2018, all eligible submission were novels or short story collections published between May 1, 2017 and April 30, 2018. Much like its sister prize (known simply as the Man Booker Prize), the winner of the MBI tends to garner much attention and sees a boom in book sales. Its history accounts for its prestige, but just as importantly, the MBI is one of the few prizes out there that splits the monetary value of its prize between the writer and translator.

Part of the MBI’s unofficial mission is to raise the profile of translated fiction and translators in the English-speaking world and provide a fair snapshot of world literature. What does this year’s longlist tell us about the MBI’s ability to achieve that goal? Progress has been made from past years, especially with regard to gender equality: six of the thirteen nominated authors and seven of the fifteen translators are women. Unfortunately, issues arise when taking into account the linguistic and regional diversity of the prize not only this year, but with previous lists as well. For 2018, only four of the thirteen books come from non-European authors, with no titles from North and Central America or Africa. This is an issue that plagued the IFFP before it merged with the MBI and marks even the Nobel Prize for literature, as detailed by Sam Carter in his essay “The Nobel’s Faulty Compass.”

Unlike the Nobel (which is not technically constrained by English-language availability), the MBI is dependent on the submissions made by British publishing houses. Although we do not have access to the submissions list, the numbers tell their own story: 108 works were submitted, but only ten languages represented on the long list. According to available statistics, most fiction translated into English comes from French, German, and Spanish. The publishing world, a market itself, after all, tends to be rather Eurocentric. Considering publishing tendencies, literary prominence, and a preference for topical literature, then, it is no surprise to see the following titles included: Laurent Binet’s The Seventh Function of Language (translated from the French by Sam Taylor), László Krasznahorkai’s The World Goes On (translated from the Hungarian by John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet, and George Szirtes), and Jenny Erpenbeck’s Go, Went, Gone (translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky).

That being said, the non-European works included in the longlist come highly recommended by readers and critics alike. Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad (translated from Arabic by Jonathan Wright) is set in U.S.-occupied Baghdad where a corpse made up of stitched-together body parts disappears. It is a topical book and already a strong contender for the prize come May. Samantha Schweblin was a favorite in 2017, and although she did not win, Argentinian literature has a strong chance this year with Ariana Harwicz’s Die, My Love, translated by Carolina Orloff and Asymptote’s own Sarah Moses. Wu Ming-Yi is the first Taiwanese author to be longlisted and his novel The Stolen Bicycle (translated by Darryl Sterk) is a moving portrayal of an orphan’s search for his father (the author-translator duo has also appeared in Asymptote with an excerpt from The Man with the Compound Eyes).

There were a few snubs too. Leïla Slimani’s Lullaby (translated by Sam Taylor) won the prestigious French Goncourt Prize in 2017. A strong marketing campaign followed the publication in January 2018 to the extent that it felt impossible to escape its buzz. Yet, the book apparently failed to dazzle the judges, with Binet and Virginie Despentes (longlisted for Vernon Subutex 1, translated by Frank Wynne) being the two French representatives on the longlist. Both works are more experimental in nature than Slimani’s rather conventional character study of a perfect nanny turned child-murderer. Just as surprising was the exclusion of Andrés Barba’s Such Small Hands (another crowd favorite, translated by Lisa Dillman) especially since three other Spanish authors made it: Javier Cercas for The Impostor (translated by Frank Wynne), Antonio Muñoz Molina with Like a Fading Shadow (translated by Camilo A. Ramirez), and Gabriela Ybarra for The Dinner Guest (translated by Natasha Wimmer).

Not all predictions were as clear-cut, however. In a sense seeing Han Kang’s The White Book (translated from Korean by Deborah Smith) was almost a no-brainer. Of course Kang would feature in the longlist. When it first appeared in November 2017, The White Book was universally lauded for its raw description of sorrow and evocative language. What’s more, in 2016, Han Kang became the first winner of the newly reinvented Man Booker International Prize with her novel The Vegetarian. The decision of the judges at the time was unanimous, even among tough competition from Nobel Laureates including Orhan Pamuk and Kenzaburō Ōe. Since 2016, the Kang-Smith duo have become a household name in the world of translated fiction.

Despite critical acclaim, the inclusion of The White Book can strike readers as a bit odd. The submission guidelines for the Man Booker International specify that the prize is awarded to the author and translator of the “best…novel or collection of short stories.” But to what extent is The White Book a novel, or fiction at all? Han Kang conceived The White Book while completing a residency in Warsaw. The book is described at turns as a memoir, an autobiographical meditation on life, or simply a tribute to the older sister Kang never met. There are short sections where the prose seeps into the territory of poetry and Deborah Levy, in her review for The Guardian, called it a “secular prayer book.” What fictional elements exist (as Kang gives her deceased sister a life of her own in the second section of the book) seem more an attempt to make peace with the past, or excise a personal ghost, rather than straightforward attempt to create a story for story’s sake.

Kang’s memoir-cum-novel is not the only work to straddle the boundaries of what constitutes a novel. Gabriela Ybarra’s The Dinner Guest takes as inspiration the very public kidnapping of her grandfather in 1977, mingling the public aspects of its tragedy with the private pain her family faced after the event. Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights (translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft and excerpted in our Winter 2016 issue) is a collection of stories documenting the history of travel and the unquenchable human desire for movement. The general consensus is that Flights is more interested in generating the sensation of change than sticking to traditional storytelling. As for unconventional form, Austrian author Christoph Ransmayr wrote The Flying Mountain (translated from German by Simon Pare), the tale of two brothers’ expedition to the Himalaya, entirely in blank verse.

By virtue of their selection, all the above titles have been deemed by the judges to belong to the realm of fiction despite the blurred lines. The Man Booker Prize, English or international, has always proven its loyalty to fiction that pushes at the boundaries between genres and forms and these inclusions are not without precedent. The IFFP had already crossed this line by including in its longlists over the years works that vacillate between memoir, essay, and fiction. A famous example is Karl Ove Knausgaard’s semi-autobiographical My Struggle (translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett) and even, to a certain extent, Kyung-sook Shin’s Please Look After Mother (translated from Korean by Chi-Young Kim).

As the judging panel changes every year, it is not fair to make the assumption that the Man Booker International Prize is trying to redefine the boundaries of fiction per se as much depends on the choices the panel makes independently of previous selections. This year’s judges have embraced the ambiguity, praising not only the diversity in content, but also in structure of the longlisted books. Tim Martin speaks directly to this fact, mentioning that these works “interrogate the idea of what a novel should be and do. There are poems, meditations, state-of-the world novels and some things which delve very deeply into private lives.”

Regardless of structure, the longlist revealed only a few surprises for most avid readers (and the shadow jury that comments on the prize each year) who were able to guess the majority of the books before the official announcement. The shortlist, however, has historically been less predictable: it all depends on how books hold up to a re-read. Readers will find out who made the cut on April 12.

*****

Read More Essays: