Describing Ghayath Almadhoun’s poetry in Adrenalin is anything but easy. The blurbs on the book call the collection ‘crucial political poetry’, ‘urgent and necessary’, ‘passionate and acerbic’, and ‘our wake-up call’, although we find out that Almadhoun’s own views on his poetry are slightly different. Written in the wake of the Syrian war, the refugee crisis, and a personal loss of his homeland, the poems in Adrenaline are formally experimentally and emotionally explosive. In a voice that is, in equal measure, full of wonder and irreverence for the turn the world has taken, Adrenalin dwells on war, empathy, displacement, suffering, love, and hatred unapologetically. Translated from the Arabic by Catherine Cobham, and released by Action Books last November, this is the poet’s first selection of poems to be published in English.

The collection starts with the poem ‘Massacre’ (which can be read at our Guardian Translation Tuesday showcase), with the unforgettable lines: “Massacre is a dead metaphor that is eating my friends, eating them without salt. They were poets and have become Reporters With Borders; they were already tired and now they’re even more tired.”

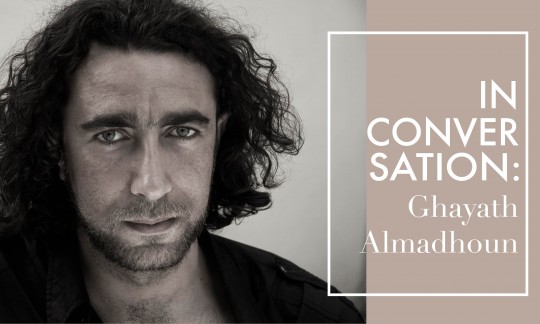

Born in Damascus, the Palestinian poet Almadhoun has been living in Stockholm since 2008. The following interview was conducted over email and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sohini Basak (SB): As a point of departure, could you tell us which writers you have been reading these days? And are you working on something new?

Ghayath Almadhoun (GB): I am now re-reading Tarafah ibn al-Abd. He was so young when he died, in the sixth century (around twenty-six years old). He is a great poet and could be described as pre-postmodern as he was ahead of his times. I’m also reading Closely Watched Trains by Bohumil Hrabal.

About my work, I have begun a new project—my fifth poetry book. I find myself in front of the question that I faced when I started writing more than twenty years ago: will I survive this time? Will I be able to write something new? And, like always, I punch the world in the face and continue writing.

SB: The weight of pain, if I can approximate it to that phrase, is present in each line of the poems collected in Adrenalin. There is a way pain is translated into language in public discourse: in the news, in public versions of private narratives, someone’s pain is made to be greater than someone else’s. You write:

. . . when my Syrian friends were dying under torture, my European friends were gently withdrawing from my wound which scratched their white lives and didn’t conform in any way to accepted Western criteria of what constitutes pain.

Could you tell us more about what you were thinking when you wrote these lines?

GA: I am made of a mass of feelings and contradictions; to be a poet is to be a Richter scale that measures vibrations resulting from human feelings and memories. Now, pain is blossoming in the backyard of my poetry—the war in my country became my breakfast, and the peace in Stockholm is my dinner, and I’m the paradox.

These are tough days for us as humans, very, very tough. To be a Syrian these days . . . Is it strange if I tell you that I feel we have become the new Jews? Forget my background as a Palestinian, I really mean it—the Syrians have become the new Jews. Of course, my comparison is not to the Holocaust, but to the diaspora of the Syrians as perpetual refugees, and to the silence of the world towards the death of the Syrians for over eight years now. I don’t have the words to describe for you the pain—we became the abnormal. It became difficult for me to mingle with other writers, since what if they asked me the typical question—“How are you?”—which would immediately remind me that I’m not well at all. Then comes the difficult part: what should the answer be to such an existential question like “How are you?” Any answer could orient us to an ugly truth which, in turn, would alienate us from each other. Our pain has gone far beyond the conventional form of pain here in Europe where I live. The people here are sensitive, you can’t remind them of how bad the situation is every time you meet them. Over time, they will prefer not to meet you.

I wish I believed in morals like Kant, to be a little optimistic, but I’m not. I’m closer to the Arabic poet Al-Maʿarri from the eleventh Century—realistically pessimistic. The lines you mention are from my poem ‘Black Milk’. Of course, it’s the black milk immortalized by Paul Celan. I know this symbol has been recycled and consumed in Western poetry for a long time, but I’m not using the phrase as a European in this context. I’ve been pondering over the meaning of black milk from the moment I read ‘Death Fugue’. Initially, I thought that Celan used it in an attempt to describe death in Auschwitz. But the Syrian Revolution made me realize what black milk actually stands for. Black milk is not the actual death of the Jews, it is the silence of the world towards the death of the Jews. Now, it is the silence of the world towards the death of the Syrians.

SB: Do you believe poetry can do more than witness?

GA: I have said it before, and still believe in it: poetry will not change the world, but it can change people, who in their turn, perhaps, hopefully, will be able to change the world.

SB: You have been living in Stockholm, but seem uneasy with the relative quietude of the place. In Adrenalin, there is a constant and surreal juxtaposition with Damascus and your absence from there…

I am the Palestinian-Syrian-Swedish refugee, wearing Levi’s jeans invented by a Jewish immigrant from Germany in San Francisco, filling my camera with pictures like a Russian peasant woman filling a bucket with milk from under her cow, nodding my head like someone absorbing a lesson, the lesson of war.

How do you negotiate with the idea of a shifting home through your poetry?

GA: Yes, my house is in Stockholm, but not my home. I’m more like a thief. I arrive in Stockholm at night, as if just to check the post, or to simply do my laundry and leave again.

Every time I feel tired, I say to myself that one day I will go back to Damascus. But when Damascus is destroyed and the places in my memory are destroyed, when the people I want to share these places with are dead, and the world is supporting the dictator of Syria and trying to recycle him to stay after his killing of millions of his people, Stockholm begins to slip out of my hands.

I’m running away instead of facing the problem: the war: I was reading about the Europeans after World War II—Polish, Germans, Russians, and of course, Gypsies and Jews, and how they tried to survive in the period after the war, and guess what? They could never retrieve what they lost to the war.

SB: In Adrenalin, there are several references to artists who made art during the wars, many of their works now classics. None of these references are a straightforward homage. It’s more complicated, as evident from your lines: “Last year the poems of Ezra Pound committed suicide in my library”; “Throw away Van Gogh’s starry sky and bring on the severed ear” and later, “I remember the novel The Outsider . . . and try not to remember Albert Camus.”

GA: These names appear in my poems for various reasons. I wrote those lines regarding Pound because, these days, I cannot read or accept literature and art from artists who have been known to support fascism. In the past, I was tolerant of Ezra Pound, or Martin Heidegger, etc. who were known fascists, since I was not able to judge, given the temporality and distance. But after I saw how the Syrian poet Adonis is now standing with the Syrian dictator against the people, I felt shame and bitterness deep in my soul. I understood how wrong I was. No more art from fascism.[1]

Literature has taken on a different meaning for me after the Syrian Revolution. The revolution has an artistic effect, by which I mean the ability of art to innovate, and to open the society to experimentation. Revolution, as I see it, is modernism against classicism, new against old, feminism against patriarchy, people against dictatorship, young poets against the patriarchal poets.

The part where I mention Van Gogh’s starry sky is from my poem ‘The Details’, written in 2012, when I was really angry about the silence towards the killing of the Syrians. I realized that the Europeans who said they did not know that the Nazis were killing the Jews were liars. Look at them now, they know everything about Assad’s killing machine in Syria and do not lift a finger in protest. In the poem, I wanted to show the European double standards:

Throw away the Renaissance and bring on the inquisition,

Throw away European civilization and bring on the Kristallnacht,

Throw away socialism and bring on Joseph Stalin,

…

Throw away Van Gogh’s starry sky and bring on the severed ear,

Throw away Picasso’s Guernica and bring on the real Guernica with its smell of fresh blood,

We need these things now, we need them to begin the celebration.

I was reminding myself, as someone who has been living in Europe, of the continent’s dark history. I was criticizing Europe in the poem and, as you know, people who are forbidden to criticise have always been the oppressed—slaves in the slavery regimes, women under patriarchy and nowadays, immigrants and refugees. Of course, Europeans do not want to be criticized by immigrants; they have this idea that if you are an immigrant you should be grateful, but I believe that all people have an equal right to criticise.

The part about Camus goes in a different direction. In the poem, I say that I’m living in Sweden: “a country containing 97,500 lakes of sweet water, my mother tells me that she is thirsty and I remember the novel The Outsider . . . and try not to remember Albert Camus”.

From the time I ran away from Damascus, feelings of guilt and loss have governed my relationship with my mother, and I fear that, as a result of this long exile, I will one day start resembling Meursault in The Outsider. I also have this nightmare of my mother dying while I’m far away in exile. I do not want to inherit the indifference of Meursault—his kind of poker-face reaction towards others comes from the real loss of one’s homeland, and it crushes poetry, crushes the borderline that should be kept between being a foreigner and turning into a stranger. It’s okay for me to be a foreigner, but I can’t deal with turning into a stranger, you know what I mean? Sometimes you are a stranger even in your own country.

But the reason I don’t want to remember Camus is because I can’t forgive him for his standpoint against the Algerian revolution. Even though he was born in Algeria, he stood with France and did not take a real position against the killing of one million Algerians during their fight for independence. He said he was against taking up arms, and he supported the French when the resistance took to weapons to liberate themselves from the Nazi occupation, and yet, he was against the Algerians’ resistance when they carried weapons to liberate themselves from the French occupation. So yes, I remember his great literature, but I don’t want to remember him as a person.

SB: Several years ago, in an interview, you had said ‘I’m really against the political poetry’. Could you please talk about this and how you would describe your poetry?

GA: Some people think that I write political poetry; it could be true from their point of view, but I see things from a different angle—I see it as an issue of relativity, and likely to be interpreted in different ways.

This is not politics, this is my life. I do not believe that my poetry is political in this sense: my poetry is only reflecting the things my life is surrounded by—my poetry is me, a mixture of my memories and experiences reflected in a broken mirror, it’s my way of digging deep into myself.

In Sweden, I have the privilege to look at things from the outside. As I see it, Swedish poetry follows two different roads, the first belongs to the majority of Swedish poets who write about their lives, and their writing reflects what I call ‘a normal life.’ There is no war zone, no dictatorship, no one is killing your family or your friends, etc. and that is great. But when I do the same thing and write about my life, even my daily emotions and experiences, it is immediately received as political poetry just because my life has a different background. So let’s make a deal: I will accept your viewpoint to think of my poetry as political, if you also will view the Swedish poetry I mention as political poetry. In the end, we are both reflecting our lives, and for that, I blame my life, not my poetry.

The other road in Swedish poetry is a road for a minority, where poets write about their wars, their inner wars or generational memories, and there I find a harmony, the hidden things that gather the feelings we share, the common denominator of sensations, and our common existential questions. I collaborated with the Swedish poet Marie Silkeberg, with whom I wrote the book Till Damaskus and together we made five poetry films. From Silkeberg, I learned how to deal with hidden meanings under the text’s surface, the side details more than the centre, and the inner layers under our words, and through her poetry, my poetry moves on to another direction. From her wars I found the ability to resist (they are different wars than the ones I had when I still lived in Syria, but now I have both wars), anyway, she is one of the minority group of Swedish poets I believe in, and find myself united with. They are the poets I bet on.

SB: In ‘The Poet Can Turn into a Wolf’, you write:

And I could have not left Damascus that autumn evening in 2008

Which would mean we never actually met

And I would never be able to tell you that you seem closer

Whenever I talk to you about Damascus

Or whenever I talk to Damascus about you

For the bodies that we see in the mirror appear closer than they really are

And those that carry our souls have been eaten by a predator

Called the Mediterranean Sea.

Many of the poems in this collection are addressed to the beloved, but they are nothing like the love poems we are used to reading. There is always something else looming over the lover and the beloved: wounds, a large sense of betrayal, languages clashing . . . I like that these poems are not insulated inside the bubble of a two-person romance. Can you talk about how you write something that is simultaneously tender and terrifying?

GA: Feelings are more complicated than reality; hate and love share the same tools in my work. The complication is attractive—poetry is not life, it’s how I describe life, the inner of the inner. It’s a reflection of memories in a broken mirror.

I do not believe in love poems in that sense, or in any genre poetry, as if you were labelling your poetry. The impact that life makes on you is complex, the reflection of life in poetry must be even more complex.

For me, even facts in poetry have double meanings, and I use the contradictions and the weakness inside me to deal with the double meanings. I’m hungry for life, and my poems are very sensual, playing with the erotic and the irony of this black comedy that we live in. Anyone can notice that my poems are full of death, but that’s because they are also full of life.

[1] Blog editors’ note: For the sake of context and balance, readers may want to read this piece regarding Adonis and the Syrian War. Adonis’s poetry was featured in the Summer 2011 issue of Asymptote.

Ghayath Almadhoun is a Palestinian poet born in Damascus in 1979. He has lived in Stockholm since 2008. Almadhoun has published four collections of poetry. The latest, Adrenalin, was published in Milan in 2017. In Sweden he has been translated and published in two collections: Asylansökan (Ersatz, 2010), which was awarded the Klas de Vylders stipendiefond for immigrant writers. He also authored Till Damaskus (Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2014) together with the Swedish poet Marie Silkeberg. Till Damaskus included in the newspaper Dagens Nyheter‘s critics’ list for Best New Books and converted to a radio play for Swedish National Radio.

Sohini Basak’s debut poetry collection We Live in the Newness of Small Differences was awarded the Beverley series manuscript prize in 2017 and will be out in a few months. She received a Toto Funds the Arts writing prize in 2017 and a Malcolm Bradbury continuation grant for poetry in 2015. Currently she works as an editor in Delhi and is a Social Media Manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more interviews at the Asymptote blog: