When I began to progressively lose my hearing at three years old, my mother fought for me to have access to both British Sign Language classes and speech therapy sessions, offering me a dual-language gateway. Through travel and education opportunities, I know phrases, sentences and expressions in other languages—both signed and spoken. But it is in English and BSL that I primarily express myself, code-switching when appropriate and, at times, combining the two together to speak SSE (Sign-supported English). This is sign language that follows English grammatical structure, as opposed to BSL structure. For those new to BSL, it can come as a surprise to discover that it is its own language, complete with its own rules, format and words—or rather signs—that have no direct equivalent in English.

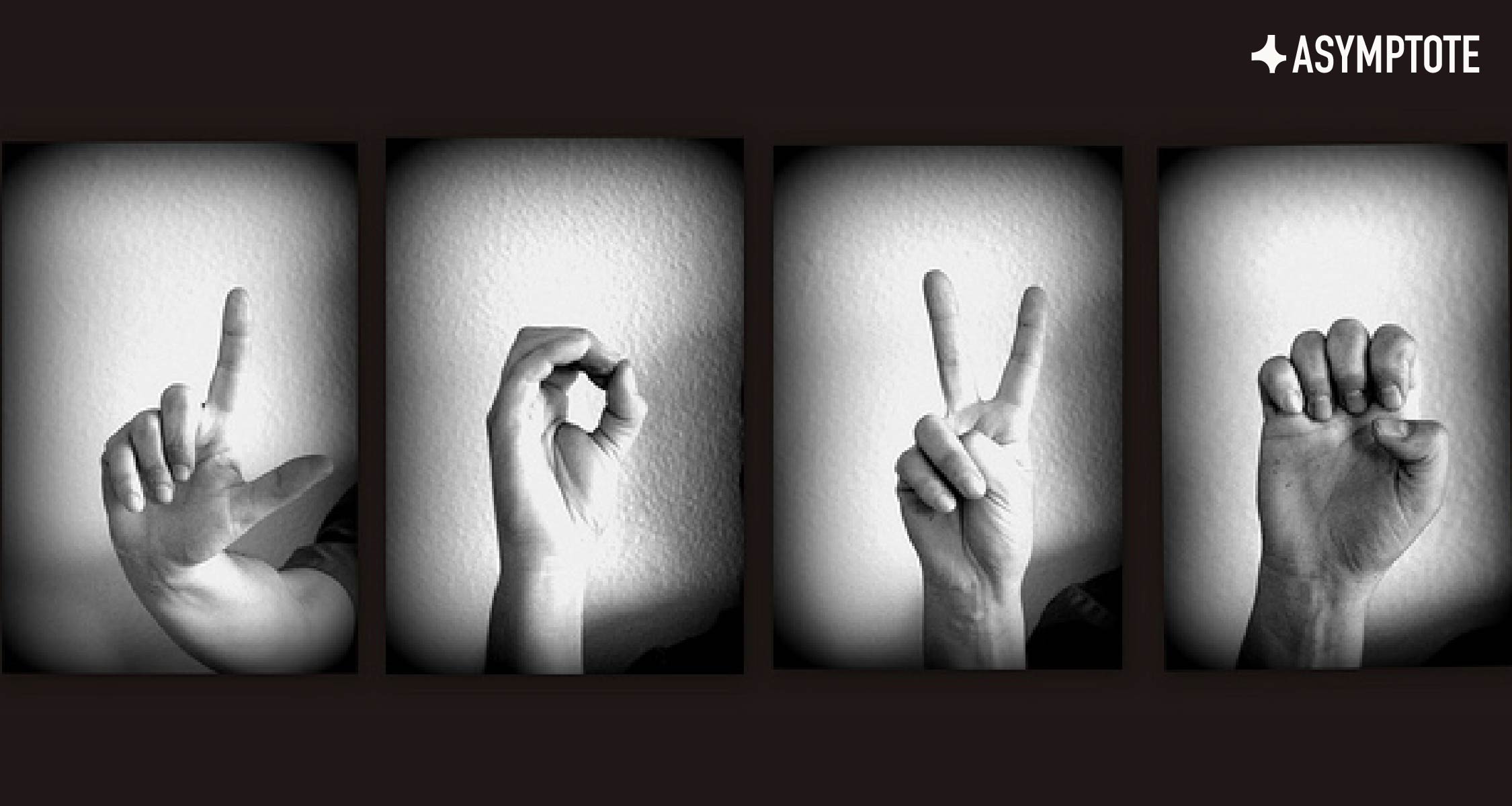

And so, on a day-to-day basis, I communicate using my hands (signing), voice (speaking), and eyes (lip-reading), as a giver and a receiver. I enjoy the literal sound certain words make as they hold space in the air. Simultaneously, and without contradiction, I love the shape of language created by fingers, expressions and the body. People also underestimate the use of the whole body in sign language – though it is primarily through the hands that words are expressed; meaning, content and colour is amplified through other parts of the body, in particular, the face.

My mother was born in Hackney, London, and my father in Karachi, with both their families originating from Pakistan. The language they speak is Kutchi, a village language that literally translates to mean the language of the Kutch people. It shares similarities with Sindhi, which is the official language of the Sindh region and borrows vocabulary from Gujarati and Urdu. As a child we were taught basic phrases, though when my parents discovered both their eldest daughters were deaf, this focus shifted to a new form of bilingualism with English and BSL.

If the language that we use is informative of the culture in which we belong, then following this logic, my bilingualism extends to biculturalism—by which I mean, in both the hearing and Deaf communities, I find a sense of belonging, a sense of self, or rather, selves. `

Still, this bilingualism, or biculturalism, is not the dualism that my parents imagined I would acquire. The term ‘mother tongue’ is a loaded one for many second-generation immigrants. It can generate complicated feelings—a sense of responsibility for some, shame for others and also guilt. It can also carry nostalgia—a sense of longing for a place or time, even if it’s not one that we truly know.

Though it is largely due to my deafness that I cannot speak Kutchi, the rate at which my hearing declined meant that it was (and still is) hard enough to pick up English. Kutchi is also a difficult language to learn, as it is not widely spoken in the Western community, and furthermore, it has no written form. And whilst it is easier than ever before to learn new languages, with all sorts of technology and apps at our disposal, there is now less incentive for me to learn it as my parents have divorced and my mother only speaks Kutchi (combined with English) to her mother, my Nanima. I only have one distant great-uncle residing in Pakistan and whilst I would like to visit the country one day, my connection with it is abstract rather than rooted in something more profound.

As I have gotten older, I feel an increasing sense of disappointment that I do not know enough of my mother tongue. I often wonder how different I would be if I had learned Kutchi when I was young and what the bicultural impact of this would be—whether by being fluent in the language of my ancestors, I would feel a greater connection to my roots, to Pakistan, to other Kutchi speakers, to my sense of self as an Asian woman. And yet, even if I could reverse time, I would not change the languages that I learnt as a child. Sign language has, and continues, to open doors for me—to people, places and opportunities. It has taught me confidence in expressing myself, even amidst people who have little to no knowledge of BSL, where by using it in its most basic mode, I can shorten the chasm between myself and others.

Strangely enough, it is when I write that I feel the impact of my bilingualism the most. I struggle with dialogue especially: I can only access conversation that is intended for me to access—and so all spoken conversation that I pick up is meaningful, even if it is not, in the truest sense of the word, meaningful. Slips of the tongues, expressions, dialect, the acoustic flow of words, rhyme and rhythm, the subtleties of human speech are not easy to pick up and so are awkwardly implemented in my writing. More recently, I have started experimenting with poetry, and whilst I enjoy it, I cannot literally hear when the natural line breaks should occur—and more than this, when sentences, even paragraphs should end. This can be seen in the original versus edited opening stanzas in a poem I wrote, entitled “My Father Lives in The Blue” (2017):

Original:

The day that we left, the rain started to fall. It was

so slow at first that he did not know it would be

incessant and unforgiving.

The floorboards laid just last summer began to sink

under the weight of the water and one by one

the hanging plants drowned.

Edited:

The day we left, the rain started to fall upwards.

So slow at first that he did not know it would be

incessant, unforgiving.

Then the floorboards began to sink

under the weight of the water and one by one

the hanging plants drowned.

These changes are subtle, but in being so only prove that the subtleties of language are, for me, a continuous struggle.

At the same time, I am so visually aware of the world because I rely on my eyes to tell me what is happening, how people feel, and to put together the jigsaws of everyday life. This may partially explain why playwriting is one of my favourite genres: the physicality of it makes sense to me and I feel more able to construct narratives within this format. It has been noted to me that there is a Beckettian aspect to my writing, as this extract from my most recent play Pomegranates (2017, inspired by the Greek myth of Persephone) demonstrates:

The Chorus nod and murmur to each other.

A lone Chorus: Forgive me, I don’t like to interrupt but I’m . . . well . . . I’m cold.

The Chorus shiver simultaneously.

Chorus: Yes it is cold. The Winter is long here.

Let us go elsewhere then.

The Chorus embrace the lone voice and leave. Meanwhile, Baubo stays standing at the centre of the room, very still as if hearing Cora’s words again.

And so, with any loss there is always a gain: knowing two languages gives me so much material to use when I write—I can think and write from a perspective that is both spatial and expressive. And whilst knowing my mother tongue would certainly give me a stronger connection to my past, it is through this “other tongue” that I have been able to better navigate my sense of self, as well as to continue learning ways in which I can express myself best—within writing and beyond it too.

Aliya Gulamani is a deaf writer who has been involved in numerous creative projects over the years, including writing short stories, making films, acting and creating plays for performance. She is a keen advocate for diversity in publishing (and beyond), and currently works as a Communications and Projects Assistant at Spread the Word, London’s leading literature charity.

*Image on display represents American Sign Language.

*****

Read more essays from the Asymptote blog: