On May 25, 1970, Joan Brossa (Barcelona, 1919–1998) spoke out at the first Festival of Catalan Poetry at the Price Theatre, Barcelona, in solidarity with the political prisoners under Franco’s dictatorship. Just a few months ago, in November 2017, the Catalan president controversially announced that in the context of the referendum for independence held in Catalonia, Spain once again had political prisoners. Captured on film by Pere Portabella in a clandestine documentary, fragments of the poems recited by Joan Brossa and other renowned names in Catalan literature are now being shown at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA). For an artist, political activist and Catalan nationalist, this intriguing exhibition that offers a new reading of Brossa’s complete works could not be more timely.

A self-professed atypical poet, it would be unthinkable to affix the name Joan Brossa (Barcelona, 1919–1998) with only one label: Recognised as the most radical poet of his generation and called by some a poet-artist and a renovator of artistic language, Brossa was a dramatist, a graphic designer, a script writer, and a director but, above all, a pioneer.

Brossa himself said that there is only one genre of literature and it is up to the artist to decide through which medium it is expressed—whether poetry, prose, or performance. In this way, Brossa dissected and experimented with everything we thought we knew about poetry, breaking boundaries and introducing his poiesis. With over eight hundred pieces including manuscripts and documents, personal objects, visual poems, films, and performance, Poesía Brossa, in typical Brossa style, stretches boldly beyond the walls of the space in which it is displayed. Up until February 25, MACBA invites us to take the position of the spectator and join Brossa in his ever-evolving process of communication.

Poesía Brossa is separated into five fields. The first room on the itinerary, “Sí, em va fer Joan Brossa” (This made me Joan Brossa), gives shape to the origins of the artist and sets the scene in which he found his voice. Brossa was drafted into the Republican army at the age of seventeen and began writing for Combate, the bulletin for the thirtieth division in which he fought. After the Republican defeat and re-training in Salamanca, Brossa left the war bearing a heavy sensation of wasted time–still explicitly present in later pieces such as Intermedi (Interval, 1993). In 1948, he joined the avant-garde Dau al Set artistic movement influencing his Poema experimental (Experimental poem, 1947), one of the first examples of his preoccupation with the arbitrary assignation of meaning to codes.

After meeting the Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto at the end of the forties and being introduced to Marxism, his work began to reflect his commitment to society and politics, loaded with underlying Catalan messages. Brossa wrote exclusively in Catalan at a time when the language was prohibited under Franco’s rule, and he made use of the politically imposed Castilian Spanish to break away from standardisation and expand the meaning of Catalan poetry.

Echoes of these fundamental elements—the Spanish Civil War, Brossa’s greatest influences and relationships, his upbringing, and the pressure his family put on him to be a banker—resonate in each of the five rooms of this exhibition.

“Jocs d’Imatges” (Game of Images), my favourite space of the entire exhibition, is a minimalistic space with cinematic dimmed lights and gallery-like rows of seemingly blank pages.

In this linear display, the onus is on the spectator to walk through the pages of these free, direct poems in search of the simplicity of everyday life and equilibrium:

Aquests versos, com

una partitura, no són més

que un conjunt de signes per a

desxifrar. El lector del poema

és un executant.These verses, like

a score, are nothing but

a series of signs to be

deciphered. The reader of the poem

is the performer.Preludi (Prelude), El saltamartí (The grasshopper), 1963

Take Pluja (Rain) with its crinkled pages and absence of words, which I would like to believe was left outside by accident, or Novel·la, one of Brossa’s many collaborations with his influencer Antoni Tàpies, a prosaic yet dehumanising compilation that depicts life, from birth to death, through its most representative events and their accompanying official documents.

It is the movement required on the part of the readers, in and around, behind and between the pages of his anthologies that truly complements Brossa’s Suites (1959–69) and Poemes habitables (Habitable poems, 1970). Displayed side by side as though paintings, in them we observe Brossa breaking away from language and moving towards visual poetry.

An exploration of the written and spoken can be found at the centre of “Altres Itineraris” (Other Itineraries). In this room, Brossa experiments with anti-poetry and scenic poetry, adopting an array of forms to communicate underlying political messages.

Moving away from their primary purpose to satisfy the onlooker’s desires, Brossa transforms stripteases into acts of political resistance (Striptease català, 1986). In Paràsit (Parasite, 1994)—a stuffed parrot perched on a tailor mannequin in front of a microphone and surrounded by scattered pages of newspapers—and visual poems such as Miró Manipulat (Manipulated Miró, 1993) and Volkswagner (1988), he exposes banks, multinational companies, and governmental organizations.

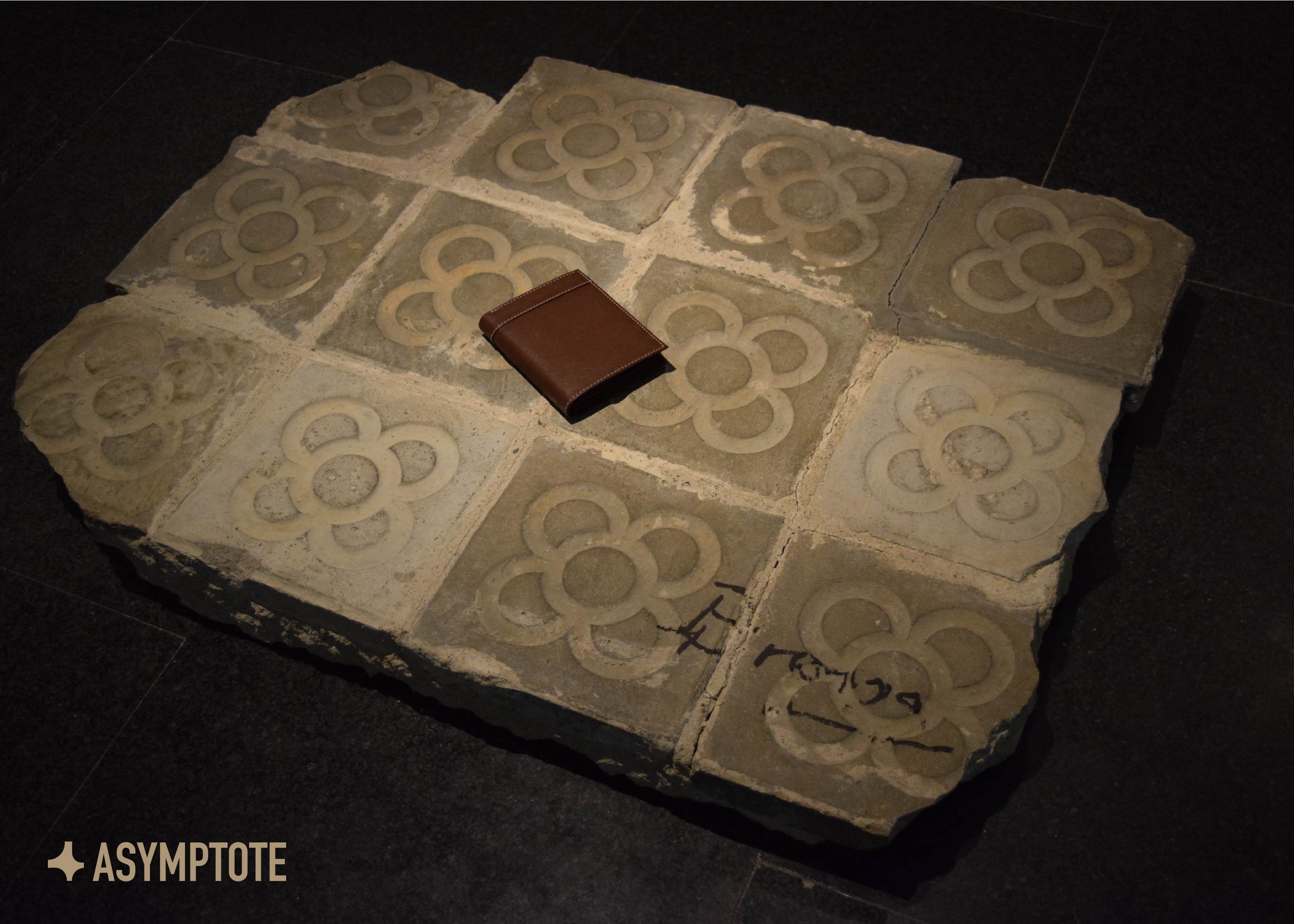

Projected images repeat Pere Portabella’s Poetes Catalans and small television sets show the assembly of intellectuals in Montserrat in 1970 in protest of the Burgos trial. In a plea for an alternative Barcelona, his organisation of an anti-tourism tour through the city starting in 1979 is conveyed in the object poem “Pèrdua o troballa” (Loss or Find, 1986)—a leather wallet on a slab of Barcelona’s decorative pavement.

In three exhibitions held in 1988 and 1989 in the galleries of Joan Prats in Barcelona, La Máquina Española in Madrid and Mosel & Tschechow in Munich, Brossa’s major works were reviewed and displayed. In a re-enactment of these earlier exhibitions of surrealism-abstraction, “Una Recapitulació Visual” (A Visual Recapitulation) invites visitors to examine this selection of Brossa’s objets trouvés. Hidden playing cards, deformed walking canes, broken reading glasses, and church pews covered in confetti; Brossa manipulated these every-day objects to reinforce meaning or reveal unseen concepts. He was interested in the dialogue between the title of the piece and the bare object itself, thus producing stark contrasts that are hyperbolically and ironically simplistic. This is exemplified in País (Country, 1986)—a football crowned with a hair comb exposing the exaggerated importance of football in Spanish society—along with Eina morta (Dead tool, 1987–1988) and Dau rodó (Round dice, 1969–1982)—two of many misconfigured tools now useless for their original purposes.

And finally, “Constel·lacions Brossa” (Brossa Constellations) is a comparison across Europe to Latin America that puts Brossa’s work into a global context alongside that of the Scottish concrete poet, Ian Hamilton Finlay, the Belgian Surrealist, Marcel Mariën, and Nicanor Parra, the Chilean anti-poet and mathematician.

Surprisingly enough, these four artists never met, however, they all moved within remarkably similar fields that are all brought together in this collective space. So close was this connection, you’re bound to mistake many works in this room for those of Brossa himself. You will see echoes of Brossa in Parra’s use of newspaper cuttings and colloquialisms (“Poetry can make you blind,” 1987), Mariën’s explicitly sexual images and Hamilton Finlay’s exploration of the movement of words on the page.

Brossa was an artist who strove to avoid stagnation at all costs, who abhorred monotony in art and was guided by his investigative spirit and this exhibition is confirmation that his poiesis has resisted the passing of time. Laden with relevance on both a national and international scale, it’s no surprise his work has been translated into more than seventeen languages worldwide. In the words of the curators, Teresa Grandas and Pedro G. Romero, “People speak Brossa.”

Rachael Pennington is an Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote.

Photo credits: Jaime Bermúdez Escamilla

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: